By Sandor Slomovits

I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t aware of antisemitism (not surprising for one who comes from a family with a history like mine. More about that later.) What’s been startling to me lately is recognizing that, until a few years ago, I never thought of myself as a possible target of antisemitism. An interaction with my father twenty-five years ago accurately describes how I have felt for most of my life in America.

In August of 1998 the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky story, like a very messy pot of soup that had been pushed from front burner to back, to front again—simmering the whole time—finally boiled over and spilled untidily on every front page and television screen. I happened to be visiting my parents at the time. My folks rarely talked politics—p perhaps a legacy of the times in their lives, both before and after WWII, when it was dangerous—even potentially lethal—to discuss government leaders or policies. But, watching the news one night, seeing the famous Clinton/Lewinsky public hug for the zillionth time, my father sighed and said, “If only she wasn’t Jewish.”

That thought had never entered—much less crossed—my mind. I was reminded, and not for the first time, how differently my father and I viewed the world. For him everything was colored by Jewish glasses, and by old, and in his case, well-founded fears. In his world, Jews always needed to be extra careful not to give people another reason to want to kill them. I, who came of age in the much more tolerant atmosphere of the United States in the 1960s despite being aware of my parents’ history and fears, felt far less burdened or affected by them.

Until recently.

Beginning in 2016, increasingly after the events in Charlottesville and Pittsburgh, and especially since the attacks on October 7, I have come to a different understanding. My life has been shaped by antisemitism.

Hyperbolic? Overly dramatic? No. My brother and I might not have even been born if a great many people, for a great many years, in a great many places, hadn’t hated Jews just for being Jews.

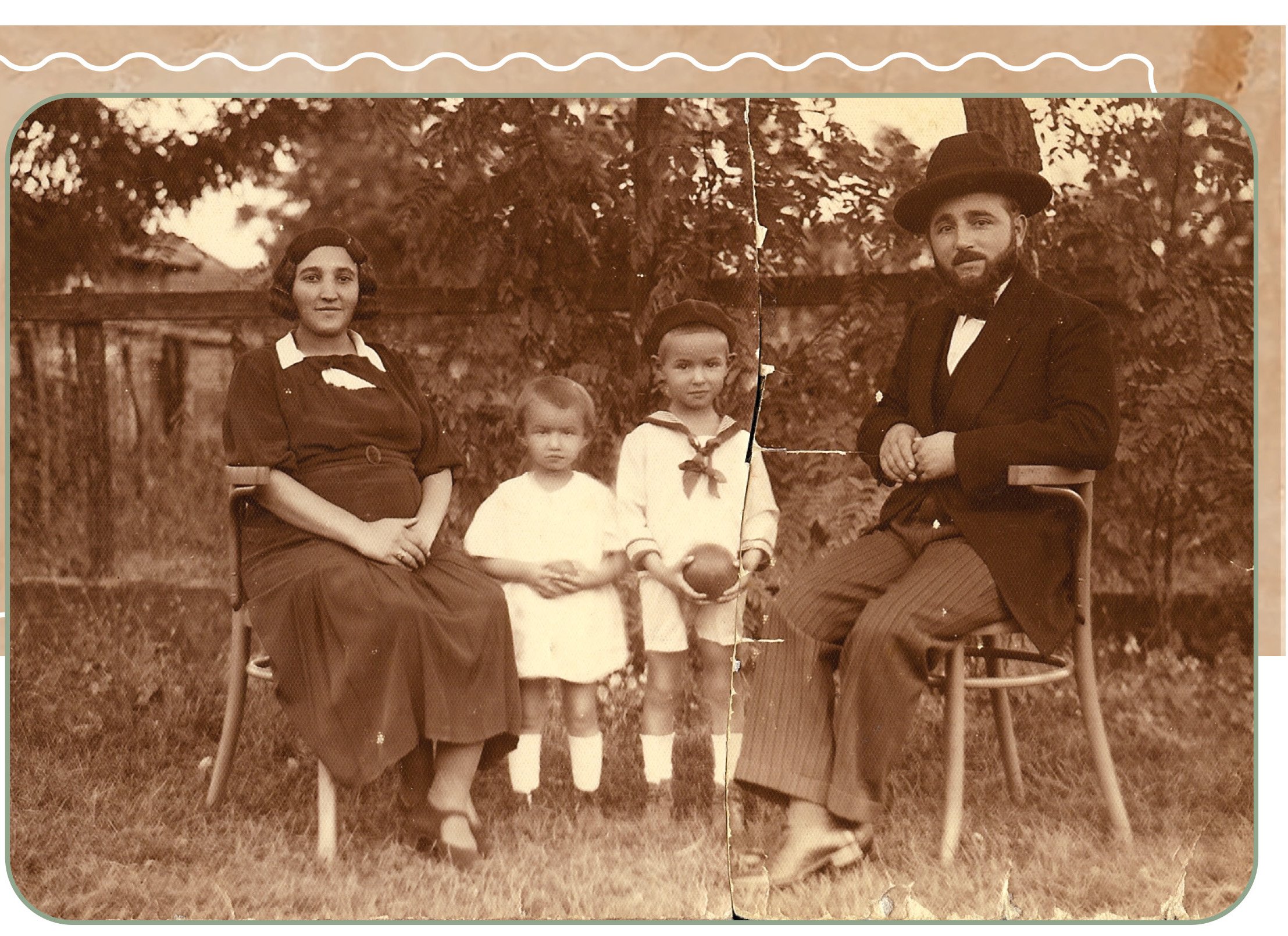

My brother and I were born five years after the Nazis murdered our mother’s fiancé and our father’s first wife and three young children. Hypothetically, if not for those tragedies, our parents would never have met, much less married, so different were their lives and circumstances before WWII.

But, extending my hypothetical thought experiment even further, had my parents met, married, and birthed my brother and me before WWII—and all of us had survived the Holocaust—our family would have included two of our grandparents, three aunts, three uncles, and at least two cousins, all of whom were alive at the beginning of 1944 and burned to ashes in Auschwitz by the middle of that year.

My life has been shaped by antisemitism. That does not make me unique. Antisemitism has shaped the life of nearly every Jew alive today. Many of us are descendants of Jews who survived or were murdered in the Holocaust. Almost every one of us is a descendant of generation upon generation of Jews who suffered discrimination, persecution and, all too often, murderous violence. Our ancestors were repeatedly forced to flee from one place to a safer one, often at the point of a sword or gun.

My brother and I were seven years old in 1956, during the Hungarian Revolution. When the Soviet Union’s troops invaded Budapest, they shuttered all the synagogues, including the two in which our father served as cantor. After the Revolution was crushed, our father’s job and career remained in jeopardy. Additionally, Hungary’s long-standing system of quotas restricting the number of Jews in higher education was still in place. Our parents knew that their children’s futures would likely also be constrained. Along with Jews throughout Europe, they knew the history of antisemitic violence in Hungary, throughout Eastern Europe which continued even after WWII, and the Russian pogroms seventy years earlier. They made the wrenching decision to leave their homeland. However, they were unwilling to risk escaping across the Austrian Hungarian border— the path taken by about 200,000 Hungarians in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution— on foot with two seven-year-old boys. They chose what seemed a safer route, after a member of the Israeli consulate in Budapest (a man who attended services at my father’s synagogue) offered them a visa to Israel.

Two years later, our family moved again because, as our father correctly observed soon after we arrived in Israel, “They don’t need cantors here. They need farmers and builders.” That was a tough ask for a fifty-year old man who had, since the age of thirteen, only worked as a cantor. Life in rural Israel was no better a fit for our mother who, aside from six months in German concentration camps, had lived her entire life in Budapest. As soon as they were able to comply with US immigration laws, they moved our family to America.

Their timing was good. We arrived in the US in late 1959. Had we reached the US ten years earlier, (continuing my earlier hypothetical thought experiment) we’d still have faced pervasive American-style antisemitism. To be sure, it was not Nazi, or European-variety pogroms; instead, it was sporadic KKK violence and quotas that barred many Jews from country clubs, top colleges and universities, and restrictive housing covenants that limited where they could live. Our parents’ timing was also good—or, more accurately, lucky—in another way. My brother and I were almost eleven when we landed in the US. We were able to learn English with almost no discernable accent before we reached puberty. Neuroscientists say that it is almost impossible to learn to speak a language without an accent after puberty. Would a career as folk musicians have been possible for us had we only been able to sing with a Hungarian and Hebrew-tinged English accent?

My life has been shaped by antisemitism. More accurately, antisemitism only established my life’s initial trajectory. It has not determined its course throughout. Once our family arrived in Israel, and two years later in the US, antisemitism’s power to influence and shape our lives seemed to disappear. For more than 65 of my 75 years, no one ever called me by any of the numerous ugly epithets reserved exclusively for Jews—not to my face nor, as far as I know, behind my back. I’m not aware of having lost any job or been denied any housing choices because I’m Jewish.

It’s not because I’ve hidden my ancestry. I haven’t changed my Jewish-sounding name. My nose is still prominent, and in most of our public concerts my brother and I sing a song or two in Hebrew. In our shows we also often talk of learning to sing with our father in synagogues and about having lived in Israel. We’ve traveled widely for fifty years; no one has seemed to care.

My brother and I are in the twilight of our careers. Would we need to consider all these things if we were just starting out now? Would I have to consider changing my name and nose and hide all other evidence of my heritage? Might antisemitism again change the trajectory of my life? Might it change my daughter’s?

I have felt horrified beyond words by the brutality and carnage wrought by Hamas and their kidnapping of non-combatants, including children and elderly people on October 7. I have felt similarly stunned by the Israeli government’s disproportionate response: killing and maiming thousands of innocents, especially children, starving Palestinians, and destroying countless homes in Gaza. Not for the first time I have wondered, how will it ever be possible to heal the inconceivable sorrow and pain now being created between these two peoples?

I am also appalled by the attacks, verbal and physical, on Jews and Arabs in this country since October 7. They echo the wrong-headed, misguided assaults on Arab Americans after 9/11, and on Chinese Americans in response to Covid. For Jews, they also awaken historical memories and fears of times when the societies in which they’ve lived have turned on them.

It seems unthinkable to me that what happened in Germany and Europe in the 1930s and 40s could happen in America. Then I remember that all too many Jews thought similarly in those days also—until it was too late.

Will my family know if it’s time for us to leave what has been our homeland? Will we ever have to choose what my parents did in 1957? And where would we find another haven?

I pray that we’ll never need to find the answers to these questions.

Sandor Slomovits is one of the twin brothers who comprise Gemini, the nationally acclaimed children’s music duo. Since 1973, Sandor, with his brother Laszlo, has toured the US and Canada and they have released over a dozen award-winning recordings and a concert video. Sandor also plays music with his daughter, Emily and is a freelance writer for a number of local and national papers and magazines.

Some years ago, I read about a study which concluded that one of the main factors in instances of heroic action is a feeling of competence. In other words, the man or woman who runs into rough surf to rescue a struggling swimmer or jumps into an icy lake to pull out a child who has fallen through the ice acts partly out of a sense of confidence about their ability to swim. There are, of course, additional factors. There is the essential one, even if merely accidental or coincidental, of being in the right place at the right time. But, even more important, is having a strong capacity for compassion, and for courage, the ability to set aside fear and act, despite danger and risk.