By Sandor Slomovits

In November of 1997, my brother and I were visiting our parents to celebrate their fiftieth wedding anniversary. We’ve known since we were sixteen, when our mother let slip one day that she was our father’s second wife, that our father had lost his first wife and three young children in Auschwitz. And long before that revelation, we’d heard about our father’s other relatives who were also killed in Auschwitz. Our father occasionally told us stories of those people. The stories often ended with, “They were taken to Auschwitz.” I can’t recall a time when I felt a need for further explanations. Auschwitz was a part of our family history that I inhaled as naturally as many other far less remarkable facts. It seemed as if it was always there—like air—not really hidden, but usually invisible.

But though our father sometimes spoke of his parents, brother, sisters, and nephews who perished in Auschwitz, he never mentioned his first wife and children. And while there were pictures of his other relatives in our family photo albums, and even one on our living room wall, we never saw any pictures of his wife and children. Our mother did tell us once that shortly after she and our father married, she’d found a photo of them in his wallet, had asked him about it and had not seen it since.

It wasn’t until I was in my late forties that I finally braved talking with my father about his first family. He did not seem surprised then that I knew about his wife and children. I asked for stories about them, asked him to describe what they looked like. And he did. Briefly, haltingly, and with so much pain and sadness on his face that, feeling guilty about opening old wounds; I always dropped the topic after a few minutes only to find myself, days, weeks or months later, feeling compelled to bring it up again. I never asked about the picture of his first family.

Finally, on this golden anniversary visit, I got my father alone and asked him if he had a picture of his first wife and children. (Not wanting to create problems between my parents, I didn’t tell him that I already knew of its existence from my mother.) My father made a grimace, looked away, and said, “No.” I wanted to spare him the pain, but my longing to see these people had become so strong that I persisted.

“Are you sure you don’t have any pictures of them? Weren’t there any left when you returned home after the war?”

Irritated, he snapped back, “You don’t understand. There was nothing left in my house. They were using it as a stable.” (“They” being the Russian Army, stabling their horses in his house and in the adjacent synagogue. This was a story he’d told us long before.)

In my best investigative reporter/prosecuting attorney manner I continued. “But you have pictures of your parents and brother and sisters.”

He went on the defensive, “I have no idea where I got those from. Maybe from one of my sisters who wasn’t taken to the camps.”

I was about to give up, but my mother, overhearing our conversation from the kitchen, called out now. “Herman, you used to carry one in your wallet. I saw it. It was of your wife and two of the children.”

Embarrassed, either at being caught in a lie, or at having his fading memory pointed out to him, my father said slowly, “You’re right, there was one picture.” Then he quickly added, “But the children were not in it.”

My mother, with fifty years of practice in standing up to him, was tenacious. “No, Herman. Two of the children are in the picture. I remember the little girl.” My father snorted in disgust and left the room.

My mother began setting the table for supper. I joined her and we worked silently. I could hear my father rummaging in his study. A few minutes later he returned, carrying a small black prayer book. Holding it open to the middle with one hand, he fingered a small photo with the other. Softly, in a tone of wonder, he said to my mother, “You are right, Blanka, the children are here.”

I reached for the photo, but he stopped me and said, pointing to the page in the book where the picture had been secreted all these years, “See, this is where I recorded your birth dates.” I looked where he was pointing and there, in my father’s beautiful Hebrew printing, was the abbreviated heading, “Boruch Hashem, Blessed is the Lord.” Below that, my brother’s and my Hebrew names, the date of our births according to the Jewish calendar, and the words, “bonai hajkirim, my dear children.”

I stared silently at the writing and the picture. I stood frozen, numb. A myriad of conflicting emotions stormed through me. Many of them I only recognized and sorted out weeks and months later.

Resentment and jealousy—Lord help me—because I didn’t have the page to myself; I shared it, of course with my brother, and also with these other children. I’d always only thought of them as my father’s first children. But I now realized—they are also my half brothers and sister.

Rage. My fists clenched, my jaw clamped. What kind of monsters could shove these people into gas chambers and then burn them to ashes?

Pain. Like the agony of someone whose anesthesia has worn off after major surgery. For the briefest moment, before I am overwhelmed by the horror of it and push the emotions away, I truly feel my father’s anguish. How he must have ached when he looked at this picture. What was it like to lose your wife and children like that?

Next came grief. For the first time in my life, I began to consciously grieve for my dead brothers and sister and for the woman who might have been my mother.

Hard on the heels of the grief came guilt—recognition of my father’s and my own. I understood that when he insisted on showing me what he had written in his prayer book before allowing me to see the picture, my father was perhaps trying to reassure me that he loved me as much as his other children. In my father’s prayer book, and maybe in his silent prayers, all his children were together. Did he ever feel guilty that he was betraying their memories by loving us?

And there were my feelings of guilt, of shame—the by now familiar guilt and shame of the child of a survivor of the Holocaust; shame that I might dare feel resentment and jealousy in the face of the horrific losses my father has endured; guilt, that my very existence mocks those losses. After all, I might not have even been born were it not for these people dying.

Eventually, through the din of all these emotions, I recognized gratitude. My father was giving me a priceless gift. He was telling me, in the only way in which he was capable, that I have been dear to him; that he has loved me, loved us, though he needed to keep his love secret, as he kept secret his love and grief for his first family. Bonai hajkirim, my dear children. He was letting me know that, contrary to the way I’ve sometimes felt, I’ve not been merely a replacement, a sad, inadequate substitute, for all he has lost.

Finally, I admitted to myself that perhaps the reason I hadn’t dared ask my father about his first family was not only to spare him pain but because it was too painful for me—too painful to contemplate that my mother and brother and I might not be first in his affections. I saw how we conspired, colluded together to keep these secrets. Perhaps I, like my father, also needed to pretend all these years that these people have disappeared from our lives.

And for the first time in my adult life, I began to think of him not as my hand-me-down father—the father who first belonged to these other three children—but as my own father, worn, torn, patched, and faded by all he experienced before I was born, but still shielding me, protecting me, as he was unable to shield and protect his first children.

An absurd memory flashed in my mind. When my brother and I were in our early teens, we loved to play Monopoly with our father. It was the one game that he always played with us, and one of the very few leisure activities in which we could engage him. For several years we played it frequently, sometimes with my mother joining us, but often just the three of us. We all took a childlike delight in accumulating the piles of fake money and the various properties. Perhaps my brother and I reveled in having him all to ourselves at those times—being able to monopolize him, not having to engage in the felt, but as yet unknown, unfair competition with our dead brothers and sister.

During these games my father was always very lighthearted, not somber or serious, not critical and judgmental, the way he seemed to be at most other times. Maybe he could relax with this make-believe wealth, this fantasy city. Maybe it reminded him of his happy life with his first family. Or maybe it allowed him to briefly forget.

I stared at the picture between the pages of the book my father was holding. I could not look at my father. Finally, I reached out and picked up the picture. I held it gingerly, as though it was a rare archeological artifact.

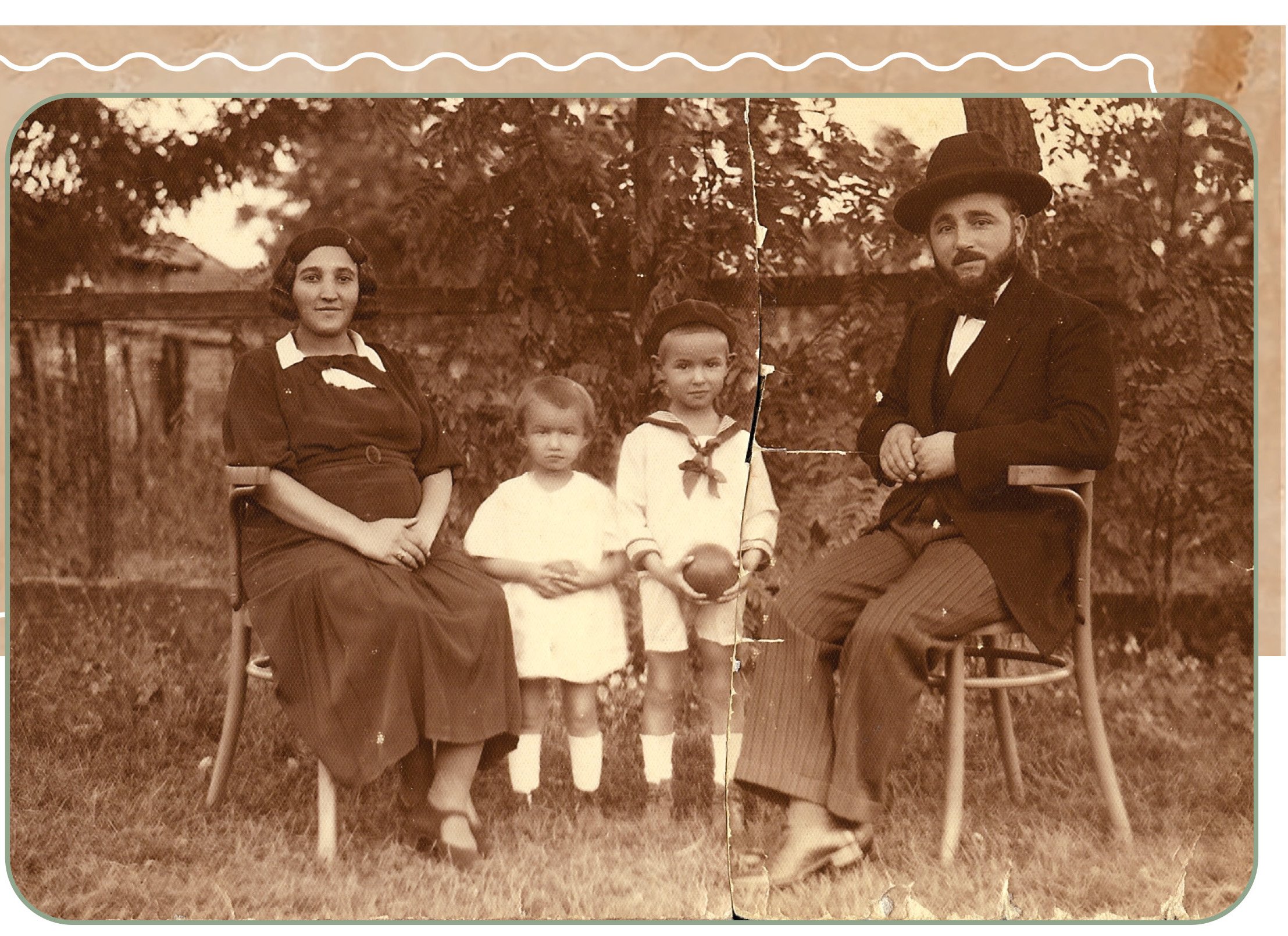

Which it is. Taken some time in the mid Thirties, it is a sepia-toned, informal, outdoor portrait of my father’s first wife, Etta, his oldest son, Ernö, and his daughter, Zelda. Etta, smiling faintly, clearly pregnant with their third child, Gyuri, is sitting on a simple wooden chair, her hands folded in her lap, wearing the traditional wig of orthodox Jewish women. Zelda, blonde and plump, about four years old, wearing a simple, short white dress and white knee socks, is standing to her left, looking suspiciously into the camera. Ernö, two years older, is standing next to his sister, wearing a dark cap, white sailor outfit with short pants, also with white knee socks, and holding a small ball in front of him.

I pulled the picture close. I tried to see if there is a resemblance between my half brother and sister and my brother and me, but I was too stunned, numbed to be able to make that judgment. To this day I can’t tell. However, I noticed with some amazement the strong resemblance between my father’s first wife and my own mother.

I noticed something else. Three sides of the photo are professionally trimmed, but the fourth, the side where Ernö stands, is uneven and rough. Suddenly, I recalled another photo, one that I had seen before, in one of our family albums. It is of my father, seated in a chair identical to Etta’s. I realized with a start—this was a family portrait that had been cut in half. I was holding the picture of the family that was torn away, destroyed in Auschwitz. My father had been hiding them ever since, keeping them safe, as he was not able to then.

I asked my father, “Why was this picture cut?” I reminded him of the other half. Did he cut it so he could fit this half into his wallet? Or had someone else cut it?

My father looked at me incredulously, “This was more than fifty years ago. Do you think I remember?”

Was it my father who cut this photo? Was it he who literally cut himself out of the picture, cut himself off from his first wife and children, as he was cut off from them by the Nazis? Was it he who removed himself from them, disappeared from the picture, as in a way he also has from us, his second family?

In the next few days, I searched meticulously through all my parents’ photo albums. I could not find the other half of the picture anywhere. I began to question whether I ever had seen it.

But I knew I had. It was the only picture of my father from that period of his life. Did he hide that picture too? Did he throw it away? Has it vanished as completely as the man he was then?

More than a year went by before the other half of the photo turned up. I moved a bookshelf my mother wanted to relocate, and the picture, along with a few inconsequential scraps of paper, was underneath it. Neither of my parents had any idea how it got there. I put the jagged edges of the two pictures side by side. They fit perfectly. Together, they formed a picture of my past; a past I never saw, yet a past I can never forget.

This essay was originally published in the Washtenaw Jewish News.

This is the story of Margot, a recently rescued tuxedo cat, and how she curled up in my heart and broke it open.