Story and Photos by Grace Pernecky

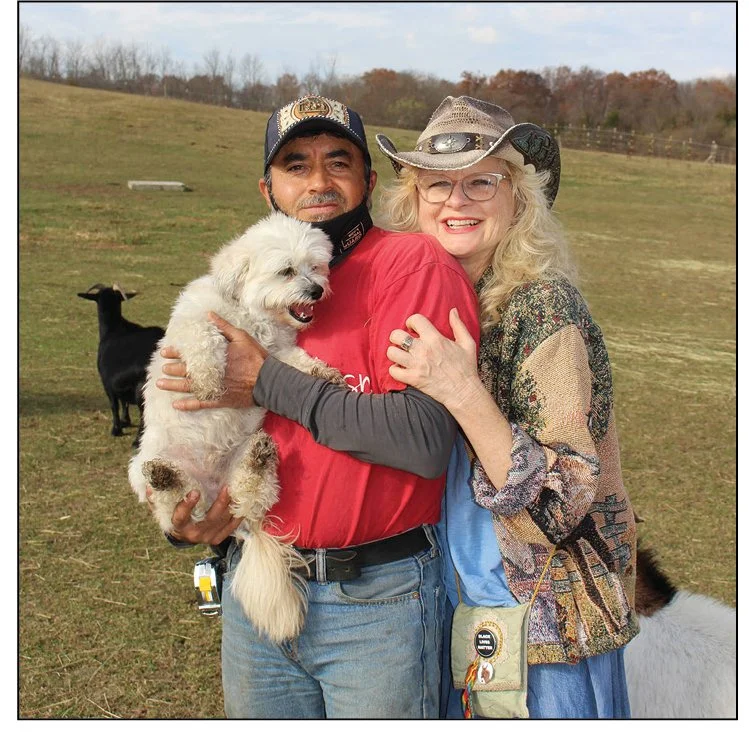

Laura Sanders, LMSW, ACSW, has been practicing in the Ann Arbor area for 34 years and has been teaching as an adjunct professor at the University of Michigan School of Social Work for 26 years. Her approach to therapy utilizes a wide variety of evidence-based and creative therapies, including trauma recovery methods, art and play therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and relational approaches through Animal Assisted Therapy. She runs her practice out of Lovingway Farm, which she and her spouse, Ramiro Martinez, have owned and cared for since 2013. She has gradually integrated many of the animals on their farm into her therapy sessions--a unique approach that is currently gaining traction in the field of social work. Sanders has found the result of partnering animals with certain clients to be astonishing. She is also an activist who advocates for justice and social change in the areas of women’s equality, the rights of children, TLBG (Transgender, Lesbian, Bisexual and Gay) concerns, and institutional racism; additionally, she co-founded the Washtenaw Interfaith Coalition for Immigrant Rights in 2008. Her farm, and by extension, her practice, are both inclusive, loving spaces that co-create an atmosphere of mental health and healing.

Lovingway Farm

The name Lovingway Farm is an apt one for Sanders’ therapeutic farm. “Instead of vegetables, we produce mental health,” Sanders told me during one of our chats.

As you step out of your car in the grassy field that serves as a parking lot, you immediately sense that this quip is true. Walking back to the horse barn, which is where you’ll usually find Sanders, you’ll pass a pen of three gray and black-mottled pot-bellied pigs and two gorgeous, pure white roosters who come right up to the fence to catch a curious whiff of a new human. Then, you’ll spot the bunny and chicken village, right up against Sanders’ house. Silkies, one of the friendliest of the chicken breeds, will cluck, call, and beckon you to come closer, and perhaps offer up a mealworm. In the distance, you’ll notice a few other large fenced-in fields and realize that other friendly creatures are likely grazing just out of sight. As you walk closer to the barn, a small white dog, full of energy and holding a stuffed toy in his mouth, bounds up in excitement ready for play. His name is Buddy. Sanders is not far behind.

Entering the horse barn, you’ll be struck not only by the cleanliness and organization of the structure that houses the largest of Sanders’ therapy animals, but also by the art. Animal-themed art, whimsical and sometimes antique in nature, adorns the walls. In preparation for the minicourse that Sanders teaches through the University of Michigan (U of M), a large circle of chairs, all facing inward, outline the perimeter of the room. A small, wooden table sits off to the side, adorned with an assortment of fruit, a homemade salsa, a large bowl of chips, and festive, seasonal decorations.

When Sanders greets you, the first things you will notice are her hat and her smile. The smile is warm, inviting, and attentive, and the cowboy hat she wears is adorned with a variety of textures, patterns, beads, and a small, decorative buckle. She listens too and is present with you, but she always has one eye on her animals, as any experienced Animal Assisted Therapist should.

Creative Approaches to Therapy:

Tools in the Toolbox

Sanders has been a practicing therapist over 30 years now, but it’s only within the past seven years that she’s been integrating animals into her work. “There’s nobody in Michigan doing what we’re doing here at Lovingway,” Sanders told me. With a bit of digging, I can see that this is true. Though there are a variety of people incorporating horses into their therapeutic practice (Equine Assisted Therapy), and yet more therapists working with therapy dogs (Canine Assisted Therapy), there aren’t many others working with a variety of different farm animals, as Sanders does; eight different species, to be exact. Dogs, cats, goats, chickens, rabbits, pigs, horses and miniature horses, and donkeys are all integrated into the relational methods that Sanders utilizes in her practice.

“I have always been creative,” stated Sanders, “and so earlier in my career, I was really interested in integrating art and different forms of creativity with healing trauma.” With a BA in Women’s Studies from U of M, as well as having been in art school for a while, Sanders’ therapeutic methods are interdisciplinary and synergistic, rooted in feminist theory as well as utilizing the healing powers of creativity. Her background has allowed her to view healing as a creative process, as opposed to the “one-size-fits-all,” top-down approach that we see all too often today. Though there’s much evidence and research that this form of therapy can be helpful, it has its limits. As Sanders put it, “A Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT) approach can certainly be a helpful tool in the toolbox, but all too often we forget that it is one tool.” CBT relies on the principle that psychological issues are based on problematic or even destructive ways of thinking, which in turn can lead to problematic or destructive behaviors. It offers that participation in talk therapy with a trained professional can help to change these destructive thought patterns and/or behaviors.

“The problem with trauma is that it really affects the way that you think. It’s not easy to think your way out of these deeper issues. They register in the body, and so, correspondingly, the healing needs to be embodied,” Sanders concluded. When we experience trauma, we use our “back brain,” fight-flight-freeze responses. These are dysregulated states. The memories of that trauma and the capacity to access what happened and talk about it is a frontal lobe activity. Sanders realized that when she started working with teenagers who’d been sexually abused or had some other trauma that it was really hard for them to talk about it. “The left frontal hemisphere of the brain is where your language centers are. There is some evidence that this center shuts down when folks are reminded of trauma that caused the back, reflexive brain to become active in order to survive,” Sanders clarified. This meant that the clients needed creative avenues that reach the senses in order to eventually talk about the trauma.

This is where tools such as art therapy, Theraplay (a form of therapy that utilizes engaging sensory and physical games and other activities to support meaningful, healthy relationships between children and important adult figures in their life), mindfulness, adventure therapy, and yes – Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT)—come into the picture. These are therapies that use your senses, that are relational in their nature, and that help awareness reach much more than just the frontal lobe of the brain.

“Instead of talking about it, we would draw it, diagram it, or be able to access the somatic experience of the events surrounding the trauma in the body, or write poetry about it, or play,” Sanders continued. “These creative activities that actually reach the senses, reach people on a more spiritual or soul level. Sexual abuse, especially, is such a betrayal. It twists young children’s ideas of what it means to love and to trust. So, these talk therapies don’t reach the senses and the psyche as well, in the way I realized I needed to be able to reach.” And from then onward, Sanders continued to explore, and to forge, new and creative solutions to her clients’ issues.

“The mark of a creative person is not that you draw well, or dance spectacularly, or write beautiful music, but that you can always think of more than one way to solve a problem,” Sanders told me. “If Plan A doesn’t work, then try Plan B—maybe Plan B is ‘can you draw it?’ Plan C might be ‘how does it feel to sit with this animal? How does this animal remind you of you?’ It’s just another avenue to reach the senses and the psyche and embody your healing.” So, instead of having one tried-and-true method, Sanders’ process works so well because she is always willing to learn more, to diversify, and to try new things.

Which Came First, The Rooster or the Hen?

How does Animal Assisted Therapy work, exactly? “When I try to figure out what animal to pair with a client, I’m asking a variety of questions that will help me figure it out: what’s the client’s presenting problem? What is it they need more of internally? And so, I have them go inside themselves, and they might say ‘confidence,’ ‘tolerance,’ or ‘patience.’ And that flags me as to what animals are good at helping bring that out in a person. I’m also asking them what animals they are attracted to and interested in. And then, using that information, I’m crafting an animal activity in my mind that I’m going to suggest. And then we’ll do the animal activity, process it, and go from there.”

AAT is not all about being comforted and soothed—it’s about metaphorizing, storytelling, and relationships. “We love metaphors here at the farm,” Sanders smiled. She believes that everything we need to know can be found by observing what’s already present in nature, if we just pay attention.

One example of this can be found in Sanders’ chickens. “I work with a lot of LGBTQ youth, and chicken behavior and development can be a really healing metaphor to some of them,” said Sanders. When chicks are little, it is impossible to tell what their gender is until they have reached a certain age, whereby they will either begin laying eggs, or start crowing. “This can be a really powerful thing for some non-binary folks to sit with and wonder about, before the gender has been revealed,” Sanders told me.

Laura works hard to make sure that the farm is an inclusive environment. On the farm tour she gives all clients at the beginning of their work together, she introduces them to Dusty and Hart, two beautiful white silkie roosters. “We call them our gay male couple, because they love each other; they are each other’s best friend and life partner, and they move as a unit. We want to instill in people who visit the farm that this is an inclusive place. So, we use a lot of metaphors like that.”

In addition to being helpful in metaphorizing LGBTQ issues, chickens can also be great models for adopted children that Sanders sometimes works with in resolving doubts, fears, and anxieties about their status. When hens are broody, they care for whatever eggs they are sitting on top of, even if they were not produced by them. “If I have baby chickens and a mom, who is a broody hen, I’ll just have these kids sit here and watch this relationship between the hen who’s not biologically related, but who is the mother for these chicks. It can be incredibly healing to these children to see such fierce love exist in that space.”

These are just a few examples of working with chickens—each species, and each individual on the farm, has their own personality, each one uniquely equipped with qualities that may prove most beneficial for any given client to form a relationship with.

How to Give a Pig a Belly Rub

“Animal Assisted Therapy is truly just another form of art,” Sanders said. “However, it requires very strong ethics of mutuality and partnership with animals, rather than having the mentality of ‘using’ animals.” One principle that Sanders always tries to instill in anyone who comes to the farm is that the animals are our partners. “That means it’s mutual. There’s something in it for them,” stated Sanders. It could be giving the chickens something interesting to pay attention to, other forms of stimulation and engagement, or a treat. “We don’t really use a lot of treats though,” Sanders cautioned, “They can actually be quite distracting. I think there’s a parallel here; we tend to use too many behavioral methods with kids where we’re rewarding and consequencing them using ‘treats,’ when it’s actually a relationship that they need.”

During a one-credit minicourse on AAT that Sanders teaches through U of M, Social Work graduate students are able to directly experience this relationship-building process with animals, and how they might incorporate this method of therapy into their own practice someday. For a full Saturday and Sunday, students come to the farm and undergo a variety of experiences and challenges that help them to better understand the work of AAT.

The first day, students get a farm tour from Sanders. They meet each of the animals in turn, while Sanders relays a variety of cases in which that particular animal worked magnificently to help heal a client’s presenting problem. Throughout the course of the weekend, each student chooses a particular animal or group of animals to work more closely with. They learn how to sit with the animal, to observe and to read, what does green/yellow/red light behavior look like for each animal, and once they’ve partnered with the animal and learned how to work with them effectively, to undergo a “challenge” that Sanders dictates to them. This ranges anywhere from getting the pigs to roll over and consent to a belly rub, to guiding the goats successfully through an obstacle course of ladders and stairs. The second day, one of the students volunteers to act as Sanders’ client, so that all the other students can observe how Sanders integrates animals into her sessions.

My first experience on the farm was as a volunteer. Sanders needs volunteers to help keep an eye on each group of animals as the students work with them, to make sure everything is going smoothly. “I can’t be in eight places at once,” she told me as she gave me my job description. She needs an extra pair of eyes on each group of students as they go off and interact with their animals of choice—one that will raise the alarm if anything starts to go wrong.

I settled in with the pig group, and although I was just a volunteer, it was impossible not to get at least a little involved with the two sweet pigs myself. Their names are Frankie and Flower, and the students in this group were challenged to both get at least one of them to roll over for a belly rub, and one of them to go into their kiddy pool, filled with water.

I’d never really interacted with pigs before besides petting them through a fence, so it felt freeing but also a little scary to be with them in such close quarters, not knowing much about pigs. I imagine that they might’ve felt similarly about me.

I learned so much about these delightful creatures just during the small amount of time I spent with them that day. Frankie was a little more friendly than Flower, but still not as friendly as the house pets I’m more accustomed to. He would sniff my arm a couple times when I stretched it out his way, but would then grunt crankily and move farther away, as if I had deliberately wasted his grazing time for such a piteous offering. I would try again and again, and the same thing would happen. I began to get frustrated; how was this supposed to be therapeutic?

The kiddy pool venture was a success, but only because an apple was involved. The belly scratch remained evasive. I vowed to attain this Highest of Honors next time I was at the farm.

Sure enough, next time I visited, Frankie ventured over my way of his own free will and, after gently butting up against my leg, rolled over for a scritch-scratch. “That’s what pigs need,” Sanders said, laughing at the expression of sheer delight on my face. “They need you to be persistent. It might feel annoying to us to keep going after them, but to them, they need to feel special, like letting you rub their belly will be worth it.” And so, my first lesson (of many) at the farm was perseverance.

Spreading the Magic

Sanders hopes to teach many more classes like this in the future, to introduce more young professionals to Animal Assisted Therapy. In fact, she has a lot of hopes for the future.

“I would really like to keep developing Animal Assisted Education through U of M. I’d also love to keep teaching my minicourse out here on the farm,” she told me excitedly. “An eventual goal is to help U of M’s School of Social Work develop a certificate program for Animal Assisted Therapy.” If such a program were to exist, it could pave the way for a more formal, evidence-based approach to AAT. Though there is much anecdotal evidence that AAT is helpful as an adjunct to mental health therapies, there isn’t yet much research in the field. Sanders hopes to change that. “Although I’m a practitioner and a teacher, I’m not a researcher,” Sanders said. “And I fully recognize how important evidence-based practices are, and how vital research is to the process of growing and developing any field of therapy, both physical and mental.” There is a growing body of research about AAT, and Sanders hopes and predicts that it will continue to grow.

Just because Sanders doesn’t identify herself as a researcher doesn’t mean she won’t share her experiences with the rest of the world. “I would love to write. I’ve had so many experiences now that have helped me to recognize that working in animal partnerships for some people is just like pouring Miracle Grow on their therapeutic goals. I’d love to write up these therapeutic stories that reflect the power of relationships with animals in helping people to heal in an ethical way, where there’s something in it for the animals, as well.”

“So, at a fundamental level, you want to spread the magic?” I asked Sanders as we wrapped up our chat. Sanders smiled, her wide-brimmed and beautiful hat bobbed up and down in clear, unwavering consensus.

You can learn more about Sanders on her website laura-sanders.com.

My sister Lisa and I often joke about our rabbit hole research inquiries. The thrill of the potential finds keeps us searching. What started as separate hobbies eventually merged to combine into writing local history as well as GENMEMS (genealogical memoirs and house histories) for clients. Lisa summed up her genealogy enthusiasm by saying, “It’s like a puzzle, or mystery, to see how everything connects or impacts each other.” That connectivity is what we all need to take a closer look at to understand our inherited (yet transformable) tendencies, how we can gather strength from our ancestors’ stories, and finally, how to keep descendants and future communities in our conscious decision-making.