By Kirsten Mowrey

Color matters. Nature uses color to attract a mate, warn of danger, lure food, and to signal hormone changes. Skin is limited in its color, so our clothing does most of the signaling for us. Mood, emotion, personality, confidence—all of this is cued through color. What colors to wear to an interview? What colors to wear on a first date? What colors to wear to an evening professional event? Neutrals with a touch of color connote professionalism and reliability, but wearing bright color is more eye-catching when out in the evening. Cultural context can change the meaning of color, but it doesn’t change the pattern of using color to communicate.

We don’t often think of where and how the color used to dye our clothing comes from, who made it, or how they made it. However, dyeing with plants found in our Great Lakes ecosystem is easily done, environmentally friendly, and just plain fun! I joined the Detroit-based collective Colorwheel to learn more about growing, creating, and using color from locally derived ingredients.

It was a splendidly sunny day in late April—a blue-sky sparkler that woke everyone up and made them glad to be alive. I stood around a five-gallon bucket with women I had just met. We were talking fashion as we stuffed our clothes in the warm water. One of the participants showed us a bright yellow sequined scarf and exclaimed how she never wore it because it’s not her color. But maybe, in about an hour, she will have something new. Not because she bought it, or traded it, but because she dyed it, herself, using Michigan grown indigo. And she’s not alone, a dozen of us have gathered from all over the state to learn to use indigo to dye our clothes. Adding pattern to a shirt, overdyeing a blouse, ombre to a skirt, or just revitalizing an old pair of jeans may not seem like social change on the surface, yet this workshop gives us a role as makers in our own lives—creators not consumers, affirmers of life in all its vibrancy.

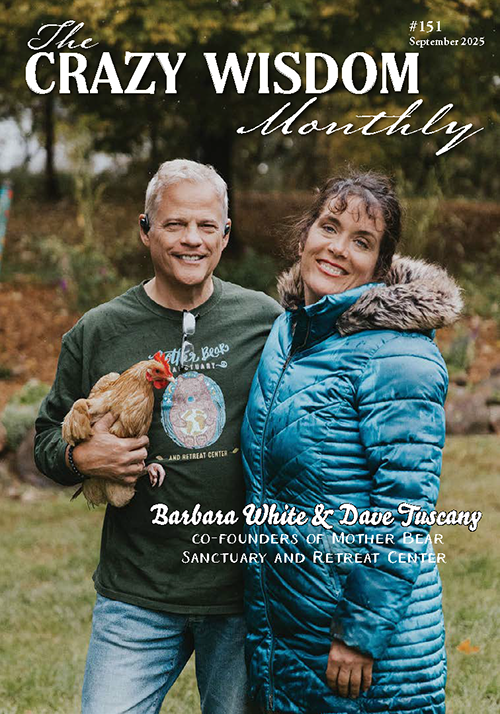

POST, on the east side of Detroit, is an old post office, now used as a store for Detroit-based artists, the home of Mutual Adoration (a design house and experimental craft workshop), and today, Indigo: Wardrobe Revitalization Workshop. This workshop is part of Fashion Revolution Week (#whomademyclothes), an event sponsored by Fashion Revolution, a UK based non-profit foundation and social enterprise whose goal is to make fashion enjoyable and environmentally sustainable. When I checked in with Wayne Maki and Claire Fox, the owners of POST, they invited me behind the scenes into the workshop area, where I could hang my coat, grab a snack, or have a mimosa before we began. Colorwheel was already present in the form of Lauren Mathieson, dressed in black, her blond head bent over the indigo vat while Michelle McCoskey, tall and graceful, arranged items on one of the large tables. Amanda Cinco-Hoyt arrived from her home nearby, long curls pulled atop her head, with more items for pattern making. All three engaged in final preparations while more participants arrived.

Colorwheel began from each woman’s individual interest in natural dyeing. All three did their own art on the art show circuit after graduating from school. McCoskey had a display of natural dyed cloth at her booth that drew Cinco-Hoyt to talk to her. “It’s unusual to find other people interested in natural dyes,” she said. Mathieson also met McCoskey through a craft show and met for coffee shortly after. All three have degrees in art, grew up in the metro Detroit area, and are passionate about foraging and growing their own colors. Their first effort was a dye garden at Cranbrook. After growing plant-based dyes, they expanded to marketplaces, then hosted dye workshops. In 2018 they brought their garden and workshops to the supportive atmosphere of POST.

“Our driving force,” said McCoskey, “is to create a more sustainable model for textile production. Textile production is the second largest contributor to pollution worldwide.” One approach is opening people’s eyes. “Getting people to understand how many textiles are in their life,” said Cinco-Hoyt. “Before my textile program, I didn’t consider how many synthetic [textiles] there are. They never break down.” Aging synthetic fabrics become smaller pieces of fabric and eventually micro-plastics, those floating pieces of small plastic that litter our Great Lakes beaches and oceans. That hip nylon top of last year is destined to become the micro-plastic you see in the photo of a dead albatross, belly full of plastic it thought was food.

Cinco-Hoyt welcomed us to the event and introduced Colorwheel and their projects. Mathieson gestured to the items on the table before her: clamps, rubber bands, clothespins, gloves, small pieces of wood. These were for us to create a surface technique on our clothing, if we didn’t want a solid color. A question about the dye garden led into a discussion on petroleum-based dyes in contrast to natural dyes, and McCoskey took it to the whiteboard. She gave a brief description of the dyes Colorwheel uses: madder, weld, and Japanese indigo, thereby gaining the primary colors of red, yellow, and blue. Using these three plant dyes allows them to combine primary colors in order to create other colors. Colorwheel tried growing a greater variety of plants early on, but found that they weren’t getting enough quantity for their dyeing needs and so reverted to greater amounts of fewer plants. The indigo we dyed with that day was Japanese indigo grown from seed in 2015.

Dyeing is an essential part of creating color in any substance. For centuries, humans used dyes made from plants. Whatever part of the plant that contained color would determine the extraction process. Madder is used in its root form, so soaking then boiling the fiber was the process, while pokeberry required berry collection, mashing, straining, and then cold or hot dipping. This process changed in the Victorian era with the accidental discovery of aniline dyes. Famous for their quick adaptation of technology heedless of consequences, Victorians embraced the synthetic dyes, and within a year of their discovery they were used throughout textile manufacturing. For colorfastness, many dyes used toxic materials such as mercury, cadmium, and lead, and still do today, according to Mark Angelo, co-executive producer of the fashion documentary “RiverBlue” Chinese environmentalist Tianjie Ma said “[these chemicals] don’t break down and they travel around the world” through the water cycle of evaporation and condensation. Though the dyeing may take place in China or India, we are all affected because all our planetary water is connected.

Natural dyes are the opposite of factory processes. They are difficult to standardize and produce “offbeat, one-of-a-kind colors” according to Rita J. Adrosko, author of Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing. Dyeing is very experimental and interactive. The weave of the cloth, the concentration of the dye, the length of time, and any pattern placement all combine to create an individualized piece. Sasha Duerr, in The Handbook of Natural Plant Dyes, points out that, “natural dyes harmonize with each other in a way that only botanical colors can. A natural red will include hints of blue and yellow, whereas a chemically produced red dye contains only a single red pigment, making the color less complex.” Hand dyeing with natural pigments makes each woman at the workshop an artist, expressing herself more personally in the clothing she colors.

“This is the indigo,” said Mathieson, as she gestured to the plastic storage bin holding a dark fluid. She stood on a blue tarp, on which was set a long table covered in plastic, upon which sat the indigo and three other five gallon buckets. She explained that indigo dyeing works through oxidation. After we dipped our items, or soaked them, we then needed to hold them exposed to the air for the same amount of time. We saw the shirt she lifted out of the dye vat, green when she first removed it, turn blue as it met the air. The number of dips and air exposure determined how saturated our items became. I brought a deeply faded pair of jeans and a white scarf I never wore. I was gambling that turning it blue might give it new life.

After we got the color we desired from the indigo vat, we moved to the next bucket—a very concentrated hydrogen peroxide, to dip our items again. The peroxide aids in oxidation. Next was the bucket of white vinegar to neutralize the cloth and dye and finally, cool water for a rinse. We then hung our items to dry and admired how the color came out. Cinco-Hoyt gave us a brief demonstration of how to create a surface design and showed us finished examples from previous dyeing classes. The possibilities were endless, and we all dove in with our clothes, twisting, clamping, and patterning before we placed them to soak in a bucket of water in order to prepare the fabric to take up the dye. The class dissolved into a varied flow; some at the table prepared a pattern, others stood at the vat, stirring and holding up their clothes to oxidize. Mathieson, who does Shibori, a Japanese type of pattern making, was giving a mini-lesson with the wood and clamps while Cinco-Hoyt assisted. McCoskey was guiding others through the indigo stations, making sure we soaked our items before putting them in the vat and not crowding it with our enthusiasm. They all worked together deftly and easily, flowing as needed from job to job or deferring to one another for teaching.

All three women create and enjoy working with animal fibers. For McCoskey and Cinco-Hoyt it’s wool, for Mathieson, silk. Wet felting brings out Cinco-Hoyt’s love of nature, and Mathieson loves indigo for “its richness of color,” while McCoskey professes a special love for goldenrod, which reminds her of a beloved park near where she grew up. Their dyeing competency created an atmosphere of harmony and surety that guided the rest of us in our uncertainty and creative exploration. That exploration was aided by the comfortable knowledge that none of what we were using was toxic—to us or the environment. The indigo we used that day will be useable for months after, with small amounts added to keep the color, and once exhausted, can be poured into a compost pile to disintegrate. The peroxide and vinegar can go down the sink.

Over time, at marketplaces and workshops, they met more and more dyers and fiber people and “realized there was an opportunity to connect suppliers to makers here in Michigan,” said Mathieson. As artists, it is difficult to find Michigan-sourced wool, so “it was a natural next step to join Fibershed in order to follow that mission to connect and revitalize.” Fibershed is an expansion of the Slow Movement project, going beyond food to color, textiles, and clothing. Originally a one-year project to source a wardrobe within 100 miles of northern California, Fibershed has become a non-profit focused on local economies, transparent product streams, carbon sequestration, and ethical consumption of textiles. Great Lakes Fibershed, founded by Colorwheel but separate from the collective, is an affiliate, with a 250-mile radius spanning the width of lower Michigan and across northern Ohio. Its goal is to restore a regional textile community, meeting needs locally rather than globally.

I had dipped and oxidized my jeans four times and was finally happy with the color. McCoskey showed me the best way to squeeze indigo from my heavy jeans so that I didn’t splash on everyone—even though we were wearing aprons, indigo, Mathieson assured us, stains everything. Her and Cinco-Hoyt’s hands were colored from reaching into the vat for smaller items that had fallen to the bottom. I dipped in each of the successive buckets, wrung my jeans, and then hung them up over another tarp to drip-dry. A few shirts and another pair of jeans were already drying on the line. Then I searched for my scarf bundle in the vat. Patty, a middle-aged woman from the Detroit suburbs who had a skirt in the vat, helped me, and we were able to leverage it out without staining our hands. I unwound the rubber bands to see what pattern I’d created. It looked a bit like a sheep head, one of those Rorschach test patterns.

When I interviewed Colorwheel, McCoskey said she was driven by the desire to create more sustainable textile production and to open minds, hearing comments such as, “I never knew you could get these colors from plants.” I could see this in my scarf: some lights make the saturated parts deep blue, others blue green, reminding me of how the surface of water changes color depending on the light. I hung it up to dry and awaited the final version. Natural colors, even these blues, look warmer, lived in, like favorite clothing that has been loved.

Currently, there are only a very few small clothing brands using natural dyes, like Sustain and Olderbrother, so as a shopper, choices are limited and pricey. But the purpose of Fashion Revolution is to change not only materials and processes of color and clothing, but the model and mindset as well. Each year they sponsor Fashion Revolution Week to promote workshops, panels, and conversation on fashion, fair wages, dignified work, environmental sustainablility, and transparency within the industry. Using our clothes longer, giving them color again, or changing their color, adding a pattern, mending, and embroidering, are all ways of changing the mindset of consumption, fast fashion, and nurturing our relationship with the planet we live upon. If we value items and refurbish them, we infuse our lives—and the objects we interact with—with our values, essence, and creativity. Changing our mindset around color and fashion is a step toward changing our future. Cinco-Hoyt, with a 15-month-old daughter, feels this keenly—she questioned having children given the state of the world. Yet, “I have great hope in what we could build as awareness of what we are doing [expands]. The comments [we hear] when we connect with people, and bring more knowledge of textiles, and growing color [gives me hope].”

In 2019, Colorwheel grew a dye garden on two city lots in the Barham Greenway, a Kresge-funded restoration in the Morningside neighborhood. “As Colorwheel, we want to ramp up to more than a garden. We are planting native plants to bring the land back [many city lots require soil building and restorative work to remove contaminants], bring in pollinators, and hopefully transform it into a community space with a workshop and education area,” said Mathieson. They also began teaching dyeing classes at the Michigan Folk School in Ann Arbor.

To expand upon Fashion Revolution week, Colorwheel arranged for a panel of speakers. While our dyed items dried, we joined the panel to hear from the founders of Colorwheel, as well as a spinner, weaver, fashion designer, and shepherdess who talked about textile production from start to finish. Many in the audience worked with fibers—there were lots of knitters, a quilter, and some weavers. Together, these women talked of their love of creating and desire to expand community, “to discover,” as Mathieson said, “how we can work together to lift each other up.”

Thanked for our attention and participation, listeners and speakers dispersed, with small groups clustered around as people asked questions or talked with a fellow maker. I gathered my items and noticed that the yellow scarf was now a muted green blue, like the depths of a shadowed stream, with the sequins winking like stars as it twisted and moved. We all agreed this color suited its owner better, and she could not wait to wear it to summer concerts and dinners. I looked at my newly dyed jeans, now the color of the deep blue sky outside, or the blue of the lakes that are the centerpiece of many summer memories. I thought of something McCoskey said when talking about dyeing. “Foraging for native plants [for dye] tells the story of where we live.” These jeans were Michigan jeans, Great Lakes jeans, worn and dyed and soon to be reworn, for new memories to fold into.

To learn more about Colorwheel and the ladies behind it, visit color-wheel.org or contact them at colorwheelmichigan@gmail.com. To learn more about textiles, the regional textile industry, and to download a free clothing guide, visit fibershed.com. To learn about changing the fashion industry, visit fashionrevolution.org. To learn about the Great Lakes Fibershed, visit their Facebook page @GreatLakesfibershed.

Within a beautiful historic house, nestled in the southside historic district of Ypsilanti, you will find a space for creatives where there are regular events, activities, and gallery exhibitions. Upon approaching the house, one will see writing on the window: Dzanc House, you’re in the right place. This is not only an indicator of having found the correct house, but also a way of communicating to the community at large that there’s a place where they belong. Whether it is for reading, writing, drawing, printmaking, knitting, crocheting, embroidering, performing, or simply absorbing the art—you’re in the right place.