By Maureen McMahon | Photography by Joni Strickfaden

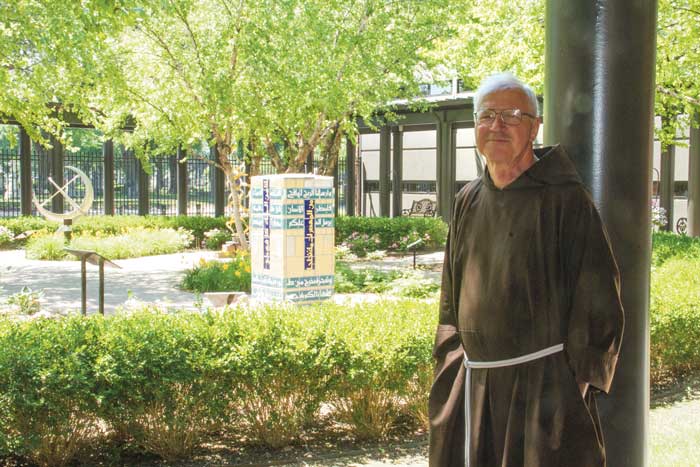

Brother Jerry Smith

I met with Brother Jerry Smith as Michigan was waking up to spring. On this beautiful morning, with the grasses just coming through the dark soil and the buds forming on the trees, Detroit and its wide blue sky surprised me with how welcoming it felt.

Driving on Gratiot headed toward Mt. Elliott Street, I was in the heart of downtown Detroit, just a mile or so away from Ford Field. It seems only small businesses are here, a Mr. Fish and a crowded shop selling second hand furniture, likely for a charity. In this place on this map, blocks of the grid are disappearing. Fallow fields sit waiting in their place.

I pulled up to a bright brick church anchored strong amidst open green plots and dilapidated, boarded-up structures. There is a man sitting on a milkcrate. He is sentinel of this corner.

A security guard standing on the grass looks me over, then softens. School children are lining up on the grass about to be escorted on a tour. I see a gardener planting bright pink annuals around the church’s signage.

This is a beautiful place, part of a bigger compound that houses Brother Jerry Smith and the Capuchin Soup Kitchen. I am here to learn more about how one charitable organization is lifting up Detroit. This Meldrum location, where breakfast, lunch, and dinner are served Monday through Friday, and people can get a hot shower and a change of clothes, is part of a much larger Capuchin charitable organization and effort throughout Detroit. For over 125 years, the Capuchin friars, staff, and volunteers have been placing their faith in action here. For children, people who are hungry, who are housing insecure, and those who need re-entry support, recovery services, and job training, this is a place of refuge, making the Capuchin Ministries of Detroit one of the city’s most respected charities.

““Brother Jerry is eager to take me to see the Earthworks Urban Farm sites, the two green hoop houses outside… Growing in neat rows are organic leafy greens, producing 12 months a year. The Ford Motor Company donated this structure and much of the soup kitchen’s bounty comes from here.””

As I turn the corner to get to the soup kitchen, I am struck by a giant modern hoop house. It has an “Earthworks Urban Farm” sign on the fence. Standing in the sunlight across from this structure were people milling about looking like they were expected somewhere — guests of the Capuchins.

In the parking lot, I pulled into a spot next to a farm stand that says “produce processing.” Behind it is another giant hoop house with plants growing on the periphery. There is a shed behind the farm stand with a cardboard sign announcing “Bike repair Wednesdays, noon to 3” and another announcing “in case of snow, rain, or heavy hail, bike repairs will be in the hoop house.”

The front of the soup kitchen is an unassuming grey door. There is a man happily working at sweeping the parking lot. He is quietly greeting people arriving for the 11 a.m. start to lunch service. He is wearing a black t-shirt and a white apron. He sweeps into a small handheld dustpan, bent down against a backdrop of large metal structures framing squares of sky, stacked like interlocking cubes two stories high. I make a mental note to ask Brother Jerry about this industrial sculpture that hovers above the parking lot.

As I enter the dining room, there is great anticipation in the air as people greet each other and take a seat at the tables, catching up until the lunch line will be formed. A lively woman at a small round table is registering voters. People are smiling at each other, greeting one another, and tipping a nod to me in welcome. I am waiting for Brother Jerry, not sure if I need to be where I am. I smile as I realize the Capuchin friars here wear brown robes. Later, in the office halls, I will see a sign on someone’s door with the image of a friar with his arms spread out: Keep calm and wear brown.

Standing there waiting for Brother Jerry Smith, I begin to get a feel for this place. It is deeply urban, yet the presence of the Capuchin mission — humble, welcoming, warm — is higher than this. The people here are Detroiters, and while they come from every walk of life, many are middle aged and elderly people of color, and there are perhaps more men in the room than women. I notice a few younger people, and though I know they serve many families, it is a school day and children are not present. As people chat, I can feel mutual respect in their exchanges, and that being here is very important to the movements of their day. People are looking each other in the eyes and speaking with open faces. Mostly laughter rises above the conversation. Lunch is almost ready.

The mission of the Capuchin Soup Kitchen is displayed on the wall. It is very uplifting and gives me a sense of calm.

Inspired by the life and spirit of St. Francis of Assisi, we:

• tend to people’s basic needs, especially the need for food,

• strive to stimulate minds and nourish spirits, and

• work to understand and address root causes of social injustice in our community.

In all we do, we seek to build alliances with others who share a commitment to this vision.

The kitchen first opened in 1929, in response to the Great Depression when people would knock on the monastery door asking for food. Over time, as the line grew to 2,000 people waiting for their single meal of the day, the friars knew they needed to do more. They worked with community members to collect food from farms, make soup, bake bread, and serve meals in the hall next to the monastery. Today the operation has matured into a stalwart fixture in the community it serves.

A friar in a brown robe helps me find Brother Jerry. Brother Jerry had been away coordinating with the head of the soup kitchen staff. He brings me to them. With a white chef’s coat on, the woman running the kitchen is very full of purpose and happy. I quickly shake her hand and she beams. Brother Jerry also greets me with a big smile. He is, in a word, jolly.

Brother Jerry, by the way, is not to be confused with Capuchin Soup Kitchen’s new director as of spring 2017, Brother Jerry Johnson, who took over when Smith was asked to serve at another Capuchin site. He starts our tour. We meet a volunteer who is distributing shower kits, towels, and fresh clothes for guests who have signed up for a hot shower. These facilities are just off the dining room, with two showers providing an average of 25 hot showers a day. Brother Jerry mentions they are about to upgrade the steam vents to commercial grade, giving me a small insight into the level of facilities management that they work in every day — meeting basic needs at high volume. There is a simple and effective system for people to select a freshly washed outfit after their shower. They are encouraged to leave their old clothes so that they can be washed and recycled into this system of donations. I smile to think of how this is grace, how it feels like starting a new day.

There is a much bigger clothing distribution operation at another Capuchin Ministries site. They distribute 1,500 articles of clothing and 11 appliances or pieces of furniture each weekday.

Brother Jerry toured me around the administrative offices, pointing out that two weeks ago they gathered everything into one room to lay fresh carpet. This building is not old and there are clearly continual upgrades refining it. It feels very intentional.

I meet an administrator who explains she is in charge of arranging HR services, including pension and healthcare, for 80 employees. There are three volunteer coordinators who lead their hundreds of volunteers. Many of the guests also volunteer, giving back by wiping down tables, serving on the food line, putting shower kits together, or helping to keep the parking lot tidy. I ask Brother Jerry if there are a lot of friars. He said there are three, as well as a priest and a Dominican nun. The rest are lay. I think of how this is a much bigger operation than I was aware of. That this is about meeting needs at the point of asking for them.

He shows me the office door of Brother Joe, a friar who is a leader in their work with substance abuse support and counseling. This includes Jefferson House, an extended residential treatment program for substance abuse recovery, housing men for nine months. He explained his job includes running four support groups a week and doing ministry to those in need of these services. The meetings held in the dining room at Meldrum in the evenings are full, with people sharing their love with each other and sharing their stories. Standing there in the hallway, Brother Jerry holds his heart and bows, saying “it is deep and profound.” I can feel his pride in this work, and more so, his pride in the people who join him to do it.

Deep and profound are words he will use two or three more times in our morning together. When he described how their services “really run the gamut” of what people who show up need, he added, “It’s holistic.” A legal services clinic, a dental office for their guests, appointments for medical services, job placement, and job training. As I think of the expansiveness of their services, I am inspired by how wide the reach.

Later, at home, I read Brother Joe’s words in their Breaking Bread newsletter summing up his experience of his Jefferson House work. He named it “hopelessness transformed.” He recently handed his leadership over to Amy Kinner, and in his goodbye note described his witness to that process as his greatest satisfaction. He recalled a man who was deeply addicted to heroin and was often in and out of the hospital. That man is now sober, married with a child, and running a small business. “He is a stunning example of the triumph of the human spirit, of the power of recovery, of life over death.”

Beyond counseling and support groups, Brother Jerry mentions On The Rise, their re-entry job training and housing program for those who have recently been in prison or completed substance abuse treatment. At On the Rise Bakery Café, located at 8900 Gratiot, so far over 70 men have apprenticed with other bakers, transforming themselves into bakers of breads, pastries, and pies — and eventually mentors prepared to help the next baker coming into the program. They learn customer service in the deli and sell at local churches. They interact with customers who come into their storefront to buy baked goods or have lunch, and also with the Capuchin volunteers. One baker spoke in Breaking Bread of what re-entry can do, explaining that the volunteers set an example: “When we are in our addictive state, we get out of touch with society. The volunteers give us context.”

““Brother Jerry is eager to take me to see the Earthworks Urban Farm sites, the two green hoop houses outside… Growing in neat rows are organic leafy greens, producing 12 months a year. The Ford Motor Company donated this structure and much of the soup kitchen’s bounty comes from here.””

Brother Jerry encouraged me to read about their Rosa Parks Art Studio & Children’s Library, a site 2.5 miles east where the Capuchins focus on connecting with children to strengthen community. Their mission includes exploring with children alternatives to violence. Gathered in a lending library of over 5,000 books, 6 to 15 year-olds and adult volunteers connect through tutoring and art therapy sessions. Kids can relax and have fun doing seasonal activities like Christmas cookie baking and decorating Easter eggs. Teen boys’ and girls’ groups and a junior counselor program focus on developing youth leadership. They run a summer peace camp with art, drama, music, dance, peacemaking classes, and field trips. Other summer priorities include a leadership camp, an academic camp, and a garden program that meets four times a week throughout what they call “the Peace Garden season.” Rosa Parks site Director Nancyann Turner, O.P., wrote that working with children to tend the flowers, vegetables, and “tire gardens” is “an incredible source of learning for our children. The garden builds community among our families and contributes to the well being and beauty of our struggling Detroit.”

Back at the soup kitchen, throughout our visit, guests greet Brother Jerry as a friend, as their uncle, as someone they are eager to joke with. They all want to talk about how far back they go with him. One man said, “I’m fifteen years an employee, but we go back longer than that — if you know what I mean.” He and Brother Jerry laugh. This is Brother Jerry’s family.

Brother Jerry is eager to take me to see the Earthworks Urban Farm sites, the two green hoop houses outside. We exit into the parking lot, again in the shadow of that huge metal structure. I asked, Is this a burnt out building? An intentional structure? An afterthought? A leftover pile from scrappers? He explained it is not the Capuchins’ but a neighbor’s who has stored frames for hanging car parts as a car is stripped. This neighbor has stacked them into an odd sculpture for storage. “We’re kind of used to it.”

In steep contrast to this, we enter the warm energy of the hoop houses at the other ends of this parking lot. We stoop under the plastic of one and into its steamy air, thick with the aroma of fertile soil and green growth. Growing in neat rows are organic leafy greens, producing 12 months a year. The Ford Motor Company donated this structure and much of the soup kitchen’s bounty comes from here. Brother Jerry shows me three impressive cisterns that collect rainwater to water the plants. He tells me the water and heating system is very sophisticated and solar powered. They won an Erb grant to pay for it.

The light is bright in here on a cool spring day. There are strings hanging in rows where soon tomato plants will climb. Brother Jerry smiled, making a circle with his hand to describe the tomatoes that will peek out from beautiful green vines rising high to the roof of the hoop house later in the summer. As we crouched under and over suspended twine and hoses, he shared with me that physical movements can be challenging because his foot is affected by MS. He made it seem very matter-of-fact, happy to maneuver around the farm with me, and gave me a larger sense of appreciation for what his work has been.

In the other hoop house an impressive plant starter operation is underway. Earthworks interns have a soil composite recipe up on a white board that they follow as they scoop, consolidate, and plant. Many of the interns were once guests of the Capuchin Soup Kitchen. This work is here to connect them to the land, to teach them about nutrition, but also to give them practical training in running an enterprise. They can work with plants and in an aviary producing honey. Here they learn in a formalized sequence, covering topics like ag business, soil and compost, seed procurement, and farmers’ markets and sales. One woman shared with me how it has changed how she thinks about food, how she has planted an edible garden at home, and taken up baking her own bread. Baking bread was common in her grandmother’s home; a part of her heritage she’d left behind until coming here. With a laugh, she said, “C’mon, I can bake my own bread! It can’t be that hard!” She was so happy to be her own bread baker.

““He explained that the soup kitchen is shifting its operational model from direct services, or what he called ‘giving them free food,’ to a more interwoven, invested model like the Earthworks intern program, where 12 interns from the community of people who use their services learn about urban farming, sustainability, and agriculture.””

Brother Jerry circled us back to the lunchroom so we could get in line for some spaghetti. He led me to a table shared with five other guests. Conversation turned to one of the guests, a television producer from Europe who had been filming the day before in East Detroit. Guests of the soup kitchen had been her guides, showing her the squat houses they were staying at and helping her to understand how to tell a story about their lives. She said Europe still sees Detroit as the Motor City, and that it’s important to show the world what is really going on here, in one of the biggest cities in the wealthiest nation.

I was reminded of my intention to understand uplift. I turned to Brother Jerry and tried to engage him in a conversation about what the city feels like to him. I asked, What does the vibration of this place feel like to you? Wondering if I was asking the right question — a concern I was met with when I asked the same question to the Earthworks Farm Manager — he carefully answered: “I’m not interested in the vibration of Detroit. I’m interested in how the guests of the soup kitchen see themselves.” He said the Capuchins have been here since 1929, and though it’s nice to think otherwise, the neighborhood hasn’t gotten better. We discussed the question, Can one place change the whole? He explained that the soup kitchen is shifting its operational model from direct services, or what he called “giving them free food,” to a more interwoven, invested model like the Earthworks intern program, where 12 interns from the community of people who use their services learn about urban farming, sustainability, and agriculture. Beyond its mission of “building a just, beautiful food system,” Earthworks is where Detroiters restore connection to their environment and community. I felt him explain Capuchin Soup Kitchen is where you go when you need a hand up.

After our meal, Brother Jerry continued to be very generous with his time. He escorted me back to the parking lot where farm meets city, where purpose finds the people who need it, and I felt this was a strong place of anchoring — a calm bay surrounded by once fallow fields that now, through vision, fellowship, and volunteerism, feed the community.

I left in gratitude with one encounter from my time at the soup kitchen that has stayed with me to this day. Moments before we went to lunch, an elderly woman walking beyond the parking lot’s chain link fence called out to Brother Jerry. We paused. He wrapped his hands around the links, leaning in to say hi. She asked after him. He knew her name and thought to ask about the store where she worked. There was so much happiness between them, as well as an undercurrent of empathy around times that are tough. He said he’d felt better. She said they weren’t going to get the grocery bill paid. “I don’t know how we’ll do it, Brother Jerry,” she said smiling. Then she swooped her hand up into the sky and proclaimed: “No matter what happens, I just throw it up to heaven!”

To get involved with the Capuchin Soup Kitchen, donate online, and learn more about their programs, visit www.cskdetroit.org.

Raising a child with special needs comes with unique challenges, but it also brings moments of incredible growth, resilience, and joy. The proper support and strategies can make all the difference—whether it's navigating therapies, advocating at school, or creating a home environment where a child feels empowered. From practical tips to expert insights, community groups and carefully curated summer camps and classes, special needs children and their families will not just get by but will truly thrive. Every child deserves the chance to shine, and every family deserves the tools to help them do it.