By Rachel Urist

The Tsogyelgar Dharma Center is a singularly dynamic and vibrant Buddhist community set on farmland just a few miles west of downtown. Now in its 26th year of existence, the community may be best known for spawning White Lotus Farms and its delicious baked goods and dairy products. Founded and guided by an American-born couple, Katie and Stuart Kirkpatrick (who have been known by their Buddhist names for decades now), Tsogyelgar includes its own self-built Stupa, magnificent self-generated Buddhist works of art (thangkas), poetry nights, CDs of beautiful and spiritual music, and dozens of local and nationwide followers dedicated to living in a conscious and compassionate way. Tsogyelgar is a living example of the fruits of creative and iconoclastic and hands-on spiritual-based activity and effort. And it is certainly one of the best examples in this region of mindfulness in action within the context of a community of spiritual seekers. What follows is a profile by our leading feature writer, Rachel Urist, of the exceptional Tsogyelgar sangha (community of Buddhists) and its inspired founders. Eighteen years ago, we interviewed Traktung Rinpoche (bit.ly/crazywisdomInterview1998), the male member of the husband-and-wife team. In this profile, we mostly focus on his wife, Tsochen Khandro, who is at the heart of the community, and whose contribution is largely unsung in the wider Ann Arbor region. (Together, they have two daughters, Lily and Ryan, and two grandchildren.)

The Farm

Driving west, Liberty Street became an unpaved country road as I watched for a sign to White Lotus Farms. Barns began appearing on either side. Suddenly, on the south side of the road, there it was, seven miles from downtown Ann Arbor. I turned left into the driveway, which became a cul-de-sac, which serves as a dirt lot. What was once farmland is now is now an intentionally planned Buddhist community. I was met by a community member who escorted me to a clapboard house. Katie Kirkpatrick awaited me there.

On White Lotus Farms, she is known as Tsochen Khandro, her Tibetan name. Her husband, né Stuart Kirkpatrick, is Traktung Rinpoche [RIN-po-SHAY]. In 1990, they founded this Buddhist community, the Tsogyelgar [So-Yel-Gar] Dharma Center. Dharma is the collection of the Buddha’s teachings, and it is the path to awakening. To study Dharma is to focus intensely on the values promoted by this tradition, in order to understand them and integrate them into one’s daily life. The Kirkpatricks bought the property in 1992 and named it the Crazy Cloud Hermitage. They bought and renovated this house, but the one they call home is four miles south of the farm. Tsochen Khandro was introduced to me by her American name, but answers mainly to Tsochen Khandro, which is what she has asked to be called here.

This space is warm and cozy and offers meeting space, a library, study and rest area. The bedrooms upstairs serve as living quarters for three community members. The house is surrounded by gardens, which Traktung Rinpoche carefully nurtures. It is a stone’s throw from the structural mainstays of the community. Tsochen Khandro and her husband pooled their collective inheritance to buy this and the other properties they own. Their parents, now gone, bequeathed them a comfortable inheritance. Tsochen Khandro was in her early twenties when she lost both her parents to cancer. Now 55, she has long been accustomed to making her own way in the world.

She gave me a tour of the grounds. The farm spans fifteen acres, with hoop-houses, barns, sheds for goats, chickens, and ducks, gardens, a pond, stone statuary, planted acreage, and buildings of varying size. Members of the community, some who grew up on the property, process the farm’s bounty. A bakery produces rustic breads, along with delicate croissants and pastries. A creamery produces an array of artisanal cheeses, many of them made with goats’ milk. The farm has produced sweets, including cajeta, a Mexican caramel-type confection made of goats’ milk. And, of course, there is organic produce galore. The farm’s business owners (creamery, bakery, farm) keep their proceeds, because the farm does not operate as a commune. The financial arrangements follow a modified capitalist system. Those who work in the businesses make salaries; they’re paid employees. Any profits above and beyond salaries belong to the whole. Several of the employees also work as the Buddhist equivalent of Catholic lay brothers and sisters, but live a vow of poverty, so the community pays for them — room and board, health insurance. “Community” refers to the Tsogyelgar Dharma Center. Everyone associated with the farm is a student of Buddhism. Some of the community members have purchased their own homes, bordering the farm or nearby.

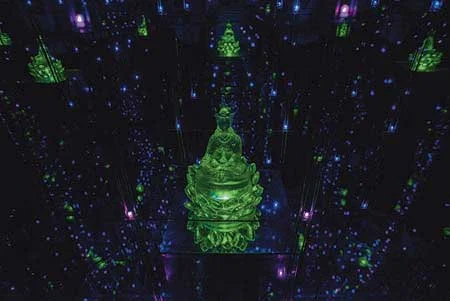

Photo from the Fa-Tsang Mirror House at Tsogyelgar. The alchemical chamber draws the MindHeart into natural contemplation. An octagonal room, mirrored on all sides, with a single Buddha statue and LED lights creates infinite Buddhas and infinite lights expanding though infinite space — all within a small room.

Tsochen Khandro led me to a penned-in area and introduced me to the goats and this year’s kids. The animals nuzzled against us, asking to be petted. Chickens strutted and clucked among the goats, almost as affectionate as their four-legged friends. Ducks waddled about, too. All the species were perfectly comfortable together. Tsochen Khandro explained that all the goats on the farm are bottle fed, so they see humans as nurturing partners. I wondered why these kids are bottle-fed, when their mothers are right there. Tsochen Khandro explained that since the goats’ milk is used for several enterprises, it is collected and disbursed as needed.

I was surprised to learn that both male and female goats have horns. The kids’ horns look ornamental, like little knobs on top of their heads. The dams’ horns are a bit bigger, slightly curved and pointed. No adult males reside on the farm, and I saw no horns longer than three inches. Tsochen Khandro explained that goats raised on industrial farms typically have their horns removed. Some consider this a cruel practice, but I later learned that this is done for three reasons: to protect the goats from one another, to protect the people around them, and to make the animals eligible for shows. The goats at White Lotus Farms, however, who are tended as lovingly as house pets, are spared this swift but painful procedure. They are adorable (they are Nigerian Dwarf goats) and remarkably affectionate. They are as cuddly as domestic pets. They graze freely, along with the chickens and ducks, and they snuggle with anyone who comes near.

Their milk is used to make several cheeses at White Lotus Farms. Among them are: aged feta, fresh feta, and chèvre. Cow’s milk is used to make hand-crafted cream cheese, herbed butter, and an assortment of hard and semi-soft cheeses. (All the cheeses I sampled were delicious.) In spring and summer, farm carts on the premises sell these cheeses, along with breads from the farm’s bakery, eggs, flowers, herbed soaps, and organic vegetables. These items are brought to the Ann Arbor Farmers’ Market and sold there, too.

We left the animals and headed to the “grande allée,” a long, grassy boulevard lined with roses and a wide assortment of other blooming varieties that explode with color during growing season. Tsochen Khandro identified many of them. Then we headed for the large barn. Inside this renovated space, a narrow flight of stairs leads to the shrine, the large room used for communal prayer. A leather armchair, like a rustic wooden throne, sits in a place of honor. Beside it is a small table adorned with ritual objects. The chair’s cushion is covered by a bear-skin, culled at the couple’s property in West Virginia. (The West Virginia property is now used primarily for retreats.) The surrounding walls feature colorful murals showing traditional Tibetan Buddhist figures and symbols. The murals extend up to the ceiling from the wooden wainscoting bordering the wood paneling below. Art and music are central to the community. Framed paintings adorn the walls of just about every building on site. A music studio produces albums created by members of the community. And there are regular poetry readings on the premises.

One local poet, excited to learn that White Lotus Farms would be featured in Crazy Wisdom Community Journal, gave me a first-hand report of the Gary Snyder event in September 2015. She gushed in recalling it. “To have a grandfather of the Beats at a farm in Ann Arbor taking questions from Clayton Eschleman about Buddhism in translation, and to have Keith there and all of the other luminaries of Ann Arbor poetry under one tent on a fall evening, and it was free, was truly spectacular!” Snyder, the recipient of many awards, was the model for Jack Kerouac’s Japhy Ryder in The Dharma Bums. Snyder, a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets since 2003, won the 1974 Pulitzer-Prize for Turtle Island, in which he urged ecological consciousness. Snyder has also encouraged people to take an interest in Eastern philosophy as an antidote to the ills of the West.

As Tsochen Khandro led me back to the house, I asked to see the farm’s trademark stupa (STOO-pah), an ornate edifice constructed by 40 community members under Traktung Rinpoche’s supervision. The structure is 35-feet tall and weighs 100 tons. It is deemed a potent living symbol of the Buddha’s mind. Meditation in the vicinity of the stupa is said to strengthen the quality of one’s practice. It is a sacred Buddhist structure, built in accordance with a very specific architectural design. Tsochen Khandro mentioned that she was eight months pregnant when the stupa was built. She painted flowers on the stupa’s corners. She did that from high up on a scaffold. “It was fun!” she said. Some believe the structure has magical powers, a notion confirmed by local legend, involving neighbors just beyond this site. We turned south, walked a few hundred yards, and there it was.

The stupa’s building crew worked round the clock to get the job done. Normally, it would take six months to build. But Traktung Rinpoche’s teacher told him the time was right to build it — as long as the project was completed by a certain date. That date was six weeks away. Traktung Rinpoche drove himself and his helpers hard, working round the clock to get the job done. The “legendary” neighbors — quiet, private people — were disturbed by the noise. When the stupa was complete, the community invited these neighbors to join the celebratory dedication. They accepted. A week later, the neighbors informed the community that following the dedication ceremonies, their prayers were answered. After eight years of trying, they conceived their first child. The Buddhist rituals next door no longer annoy them.

My meetings with Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche were delightful. Each is a lively conversationalist. Both are comfortable in their skin. They appear honest, open, and warm. We met face to face, by phone, and email. Still, it took a while to get a clear sense of what Tsochen Khandro does at White Lotus Farms. This may have been because our conversations were fragmented. Or maybe they assumed I knew more about Buddhism than I did. Or maybe Tsochen Khandro is unaccustomed to talking to outsiders about what she does. Slowly, however, a picture took shape.

White Lotus Farms represents the business arm of the Tsogyelgar Dharma Center, which is the spiritual center of this Buddhist community. To be a “member” means to be among the student/practitioners who gather for classes, retreats, and sundry celebrations. Tsochen Khandro described the community as something akin to “a monastery or a Jesuit school.”

The farm businesses operate collaboratively — as opposed to the spiritual center, which is run by Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche, who make all the decisions. When they started the Dharma center in 1990, word spread quickly. Hundreds of people came. Classes, Sunday practice, and every other gathering were crowded and a bit chaotic. People would fly in for a weekend then leave. The couple took stock and established basic criteria for membership. These days, on any given Sunday, around sixty people show up for morning Dharma practice in the shrine. Tsochen Khandro describes these assemblies as akin to church. Retreats are a different story. They have put a limit on 100 people. Some come from other countries for these events, which can range from two days to four weeks. There are also dues. To be a student and member of the community, one pays $60 per month and works on the property. Those who cannot afford to pay, don’t. “There isn’t that much structure,” Tsochen Khandro noted. She added: “We want the community to continue after we’re gone.”

Almost in passing, Tsochen Khandro noted that she and Traktung Rinpoche took their ordination vows 17 years ago at a Center in Wales.

"It was a sweet and symbolic moment for us to reaffirm our connection with Guru Rinpoche, which we have maintained over many lifetimes. But it is important to understand that in Vajrayana, anyone may decide to become a teacher. It is understood that one’s qualities as a teacher — if they are real — will bring students and create a sangha. And if they are not real, things will fall apart naturally. So ordination is not a certificate to teach. We had already been teaching for eight years at that time. Our lives were already dedicated to serve beings, in the tradition of Guru Rinpoche."

Hearing them talk of their many lives gave me pause. To my ears, some of what I heard from Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche was wild. I turned to a historian, an expert on Southeast Asia, for his thoughts on reincarnation and memories of past lives. He said that in Burma, for instance, discussions of past lives are commonplace. It is also not unusual to hear young children recite hundreds of pages of sacred text, which are assumed to have been learned in past lives and retained in memory. I made a mental note comparing this tradition with the Jewish notion of “gilgul neshamot,” the Kabbalistic view of reincarnation. “Gilgul” means cycle or wheel. “Neshamot” means souls. Gilgul neshamot signifies a kind of recycling of souls. Still, it was jarring to hear of “experiences” from past lives. When I referred to their “claims,” I was corrected. These are not “claims” but “memories.” Within the community, such notions are discussed casually. They are givens. I needed to understand how these concepts fit into modern life in Michigan in the 21st century.

I also needed to get a better sense of what it means to “practice Dharma.” I knew that Buddhism is a tradition that promotes spiritual awareness. It teaches its followers to be compassionate, clear-minded, truth-seeking, awake. It values loving-kindness and wisdom. It seeks to alleviate suffering through healing and transformation, so that all beings may experience peace of the highest order (Nirvana). It underscores the concept of impermanence and urges its followers to divest themselves of material attachments.

““He said that in Burma, for instance, discussions of past lives are commonplace. It is also not unusual to hear young children recite hundreds of pages of sacred text, which are assumed to have been learned in past lives and retained in memory.””

I was surprised to learn that Buddhism is not a theistic system. While Buddhism is often categorized as a religion, it can be seen as something closer to a tradition or a philosophy. In an interview of 1998, Traktung Rinpoche said: “The non-theist path of Buddhism is more likely to lead one to liberation than the theist path, because there are fundamental mistakes on the theist path — God and Self being two of them — because neither one exists.” This helps explain why Traktung Rinpoche, who was raised in a high-power, intellectual household and who holds a B.A. in comparative religion, quotes so many philosophical and religious thinkers from different cultural backgrounds. They include Herbert Marcuse, Martin Buber, and the Baal Shem Tov. Traktung Rinpoche was always a voracious reader, and he continues to read widely.

His father was a philosopher. His mother, Jeane Kirkpatrick, was a political scientist. They were renowned academics who traveled with their three sons all across the world. Ronald Reagan named Jeane Kirkpatrick U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. She was the first woman to serve in that role, and she was deemed indispensable to Reagan despite her affiliation with the Democratic Party. At the Kirkpatrick’s dinner table, discussions ranged from philosophical to political to religious. Cultural differences were not only discussed, they were experienced first-hand, since the family spent years in Europe and the Far East. Traktung Rinpoche’s multi-lingual mother read Plato aloud to her sons during car trips, and the boys were expected to offer opinions on the concepts proposed. Young Stuart (Traktung Rinpoche) was always intellectually curious. He was a thinker. But he also was visited by visions — he calls them “memories” — which frightened his parents. By the time he was eight, he understood the dangers of divulging his “daydreams,” as his parents called them. For him, there was something surreal but not unnatural about these visions. They were memories of past lives. But when he spoke of them aloud, he sparked parental concern. They wondered whether they should send their son to a psychiatrist. He learned to keep his visions to himself.

Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche, however, have no trouble appreciating one another’s memories of past lives, and as a couple they have invested their energies and resources in the well-being of the community. Using their pooled inheritance, they have subsidized the professional aspirations of several of their students, underwriting their tuitions and supporting them through art and culinary schools. Buddhism discourages idleness. It encourages self-sufficiency and productivity. A practical livelihood is essential if one wants to achieve the higher, metaphysical goals (peace and harmony).

As instructors of Dharma, Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche teach by example. To help their students achieve the higher goals, they offer several forms of assistance. Finding inner truth is more easily done if one has food and shelter and if one is not engaged in disputes. Meditation figures large in the community’s endeavors; it is key in reaching the highest of personal and collective goals. It is assumed that life is best lived simply, without pretension or undue ambition. It is always important, too, to help others.

The simple life promotes authenticity, which is a key element in finding inner peace. While most traditions valorize wisdom, learning, and compassion, Buddhism’s goal is to achieve enlightenment. This requires mindfulness and intense focus. When community members speak of Tsochen Khandro, it is clear that she is a living example of the adage: Action speaks louder than words.

Destiny Calls: The Fateful Meeting

Tsochen Khandro met her husband-to-be 33 years ago at Kenyon College a week before her graduation. She was 22, he was 23. As she tells it, their initial meeting confirmed the sense she’d had since childhood: that she was looking for someone; that there was someone she needed to meet. Her mother always thought her daughter crazy for harboring that idea. But at Kenyon, when he turned to ask her what time it was, she felt “struck by a lightning bolt,” as she put it. Her longstanding meeting with destiny had just occurred. “From that point on,” she added, “we were together.”

The meeting may have felt preordained, but Tsochen Khandro was not happy about it. She went up to her room and cried. As she told it:

Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche with some of their second generation students

"I freaked out. He was a Rajneesh disciple then. He dressed in red. That did not fit in anywhere with me. It was distressing. I was a nice Catholic girl. But later, in the bookstore, he was talking with a group of people when I walked in. We looked at each other. He put his arms out, and I walked in. We were inseparable after that."

They still sing each other’s praises. They now have two daughters and two grandchildren. Traktung Rinpoche is still her best friend, her inspiration, her soulmate. And she is his.

His visit to Kenyon College came during his time off from school. The friend he visited at Kenyon was also Tsochen Khandro’s friend. When this friend brought them together, he introduced Traktung Rinpoche as “Pranama,” which was what he was then called. In fact, Tsochen Khandro never knew her husband by his original name, “Stuart.” They left Kenyon College together and she joined him at the Rajneesh commune in Oregon. They stayed there for six months.

““But at Kenyon, when he turned to ask her what time it was, she felt “struck by a lightning bolt,” as she put it. Her longstanding meeting with destiny had just occurred.””

When they left Oregon, they returned to Michigan. Tsochen Khandro, who is from Grand Rapids, has always considered Michigan her home. They came to establish Tsogyelgar Dharma Center. Traktung Rinpoche was Swami Prem Pranama. When she was ordained, she chose the name “Tsochen Khandro.” Both had taken vows as a Lama, by then. The official role of teacher went to him.

In this spiritual community, names have heightened significance. “Tsochen Khandro,” her Tibetan name, is an honorific meaning “sky dancer”; she has left the confinements of earth for the vastness of open space. “Tsochen” means great lakes. Traktung Rinpoche’s previous name, Pranama, means worship. The name was given him by a Hindu teacher in whose ashram Traktung Rinpoche lived. Before that, he was known as “Khepa,” which is actually a title, not a name. It’s Bengali for “aimless, worthless, stinky beggar” — his way of signifying his lack of pretense in the presence of his teachers. It’s a name that put me in mind of the Jewish legend of the Messiah, whose harbinger will be a beggar — a creature wrapped in rags, possibly stinky, and certainly without clear signs of dignity, let alone holiness. If people take pity, if they share their earthly goods with such figures, the Messiah may reveal himself. If not, the Messiah may decide the world is not yet ripe for redemption. In other words, the world has more than one culture that nourishes the idea that recognizing promise in the lowly may be key to affecting change.

When Traktung Rinpoche was Khepa, Tsochen Khandro was “Acala [Ah-CHA-la] Devi” — a name her husband gave her. Devi is Sanskrit for “Tsochen Khandro,” or “sky dancer.” “Acala Devi” means “immovable and unshakable in her commitment to all beings through compassion.” These days, members of the Tsogyelgar community feel that Tsochen Khandro embodies the meaning of her name: “female holder of wisdom of the great lakes.” The student who explained this to me added: “We call those who teach us by their formal names. Of course, we do this for our benefit, not theirs.”

It is interesting that for Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche, renaming themselves serves not as pretension but as a route toward greater authenticity. For many, a new name can signal the reinvention of self, which can smack of artifice. For them, however, delving deeper into Buddhist tradition seems to bring them closer to awakening (enlightenment).

The names of traditions are also important. This community follows the Nyingma Buddhist lineage. When Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche switched from teaching the foundations of Buddhism to the formal teaching of their preferred Bhutanese version of the practice, Vajrayana with an emphasis on love, they changed the name of the community to “Tsogyelgar.” Four years ago, the farm was named White Lotus Farms. Once they learned to identify serious students and set parameters for membership, the chaos of the early years waned. The community is now stable.

According to Traktung Rinpoche, Tsochen Khandro’s competent and compassionate oversight is what keeps the farm humming. Actually, he can’t praise his wife highly enough. Alternating between “Katie” and “Khandro,” he extolled her virtues and their benefits to their community of Buddhist practitioners, or “sangha.”

"She’s an amazing, beautiful woman with profound wisdom. Our teacher called her Rinpoche. Normally women aren’t given that title. None of this would be here without her. She’s the heart and humanity of it. Katie’s the person to whom people go when there is a problem, a dispute, a miscalculation. She is good at solving problems, be they technical or interpersonal. I am good at what I do — teaching methods and meditation, the philosophical view of our path — but in terms of making the community a beautiful place where people thrive, that’s her forté.

My teacher used to tell me that Katie was an emanation of Tara, the mother of the Buddhas, the embodiment of compassion in female form. Katie’s like the mother of us all. Most people in the sangha say they feel she’s like their mother. She brings something sacred to this community.

The joke among the sangha is that one hour of talking with Katie is worth a year in psychotherapy. Khandro has helped couples in our sangha. We have a number of couples, now divorced, who remain here. Khandro helped them separate gracefully. She’s the heart of the community. It’s strong relationships between people that keep the community strong.

Katie helps people avoid a “twinkie faceness,” a falseness, the façade of spiritual serenity. She keeps us from becoming spiritual fakes. That’s always the danger. Any spiritual practitioner who says he’s never faced that danger is fooling himself and you."

At some point in our scattered conversations Tsochen Khandro mentioned that she feels a kinship with Michelle Duggar of the reality TV series 19 and Counting. I had never seen this show and had no idea who Michelle Duggar was, so I watched a few episodes. I learned that Michelle Duggar is the Arkansas-based evangelical mother of nineteen biological children, two of whom were born during the course of the show’s run. She is described as “compassionate, loving, giving, calm.” She has home-schooled all her children. She never raises her voice. She is rarely rattled. She is pretty. As I mulled over these descriptions, I remembered that Tsochen Khandro had responded to my early request for an outline of her days by saying: “My most accurate job description would be ‘mother of all beings.’”

Given the maternal role that Tsochen Khandro plays in the sangha, it makes sense that she would feel comparable to Michelle Duggar. The nurturance she offers is extensive. In addition to providing emotional support, she researches the farm areas that interest her and lends that practical knowledge to the farm workings. She helps in the dairy. She has become an expert on goats and contributes in a hands-on way to their care.

She also brings to bear the psychotherapeutic training she has had. That, along with her mediation skills, are indispensable in her weekly meetings with the seventeen business members who run the community’s three enterprises: the creamery, bakery, and farm. They meet to discuss what and how they’re doing, to consider what can be modified or improved, and to resolve any disputes that might have arisen. According to one member, “She brings balance and harmony to the community.”

She also makes herself available beyond the space and time of those weekly meetings. She can be found in the art room, where she tackles various projects, or in the music studio, where she records sacred music. Or she is in other settings round about the farm. Sometimes, she teaches formally in the shrine room. Wherever she is, people come to her with questions. She offered examples:

- Where should we house so-and-so, who’s coming to visit?

- Do you know of a sitter who might watch so-and-so’s children?

- When should we place the food order for summer retreat?

- How can I help my child to stop being sneaky?

- Does this look like a tumor on my dog?

- I am fighting with my husband. May we speak to you?

- Can you look at this list and tell me if anything is missing?

- Could you proof and approve this ad?

- The Creamery drain is clogged. Will you come look at it?

Tsochen Khandro tries always to respond from a Dharma point of view. She helps others to approach life’s challenges from that point of view, too. She sums up her approach to life with these words: “I wanted to know the end of suffering. And by following this path diligently over time, I know there is an end to suffering.”

Among the additional things Tsochen Khandro does that Traktung Rinpoche so appreciates are (1) her careful editing of his writings, and (2) her raising their five-year-old grandson, Arlo, born to their teenage daughter, now 24 and currently completing her studies in Paris, France. Tsochen Khandro is comfortable with young children and enjoys their company. She ran a preschool for several years. She considers it an honor to care for her grandson. “He helps me with the goats,” she notes with a smile. A new granddaughter, Naomi Kate, was recently born.

Our first meeting lasted two hours. Tsochen Khandro’s general description of life on the farm mirrored the words on White Lotus Farms’ website:

"As Buddhist practitioners, we are motivated to bring beauty, truth, and goodness to our community through how we interact with our land, our animals, and each other. At the heart of everything we do is mindfulness and care, with a passion for quality and sustainability. Our farming practices are built on a model of true sustainability. We use innovative biodynamic and organic methods; our produce is USDA certified organic. We believe great produce starts with great soil, and strong focus on soil enrichment leads to food that is nutritious and flavorful. We are Buddhist practitioners dedicated to finding beautiful and virtuous ways of making our way in the world, plain and simple. Integrity, honesty, and authenticity are at the heart of our tradition and inform our relationships with customers, community, and the larger world."

During my guided tour, Tsochen Khandro showed me the outdoor stove that is used to create “biochar.” When biochar, or burnt wood (it becomes a charcoal-like substance), is added to soil, two things happen. First, the soil’s nutrient quotient is enhanced, and second, the retention of those nutrients is extended. In tandem with the University of Michigan’s School of Engineering, White Lotus Farms will soon install a line from the stove to the hoop house, providing heat for the growing plants during winter. In the past, solar power heated the hoop house in winter. In the future, heat from the stove will prolong and enrich the winter growing season.

As I prepared to leave the farm, I admired the glow of mutual admiration in this couple. I mentioned this to Tsochen Khandro. Her response surprised me. “We’re still human,” she said. “I can get snarky.” Still, they keep a remarkable equanimity, and they seem to be on the same page about most things. For instance, in addition to having given financial support to certain members of the farm, they also established a nonprofit foundation that founded, funded, and sustained an orphanage for girls in northern India.

Members of the community offer a much wider lens through which to examine Tsochen Khandro’s role. Here is what some had to say.

The Herd Manager

Tammy grew up in a military family, mostly in California. She was taught to sacrifice for others, to “man up,” to avoid living just for herself, to benefit by giving. This background shows when she said: “You can give so much more of yourself by being part of something bigger, something noble and good.” For her, finding Buddhism was finding a path to live for the benefit of all beings. Tammy has lived in Ann Arbor for twenty years. She has had a presence at Tsogyelgar since it began, though has only lived here for the last five years. She stressed that she came to this farm because she is a student of Buddhism. She also loves animals. “If a goat starts kidding [giving birth] in the middle of the night when it’s cold, it tests your mettle. You do whatever it takes.”

Before becoming a farmer, she was a blacksmith. Some of her decorative metalsmithing adorns the farm. In college, she considered careers in both medicine and academia — until she realized that she favors outdoor work. Both farming and working with metal involve “wrangling with the elements.” She is happy with her choice. “I work by myself. It’s me and the animals. Interpersonal problems are minimal, if at all. We have farm meetings once a week, when we put our heads together. Khandro is unbelievably skillful in untangling stuff between people.”

For Tammy, as for her colleagues, working in a community that nourishes both body and spirit helps to dispel many of life’s conundrums. The chores, however taxing, are a labor of love.

"I take care of the goats and the dairy. The goats get milked twice a day at the milking parlor. Our herd is made up of mothers and children, which is fun. Caring for milking mothers is a big job. We think of our does as Olympic athletes. They need a stress-free environment. We ask a lot of them — to give milk for ten months. So we give them the best. We don’t cut corners. A good part of our work is the kidding in March, April, and May. Khandro is a big part of that. In fact, she is a huge inspiration for me in all of this. We have fifty mothers, and we expect about ninety kids this spring.

During kidding, when we have problems, she can troubleshoot. Sometimes babies have trouble coming out. Khandro knows what to do. She spends a lot of time researching. She knows goat anatomy and physiology, and she loves animals. She also blesses each baby goat after it’s born. She doesn’t make a production over it, and if you’re not watching, you won’t see it. But that’s huge to me, to have her bless each baby goat. The heart of my job is caring for the animals, not just tending. Her blessing is priceless.

I also am in charge of the chickens and ducks. They don’t need my attention as goats do, but I love the poultry. We have 125 chickens. Our poultry are all free-range, but we need to keep an eye out to make sure the environment stays safe. Often they’re scrounging around under the trees. It’s moister there. They find worms and grubs. When there’s lots of insect activity — in warm weather — they go after the insects. In summer, when there’s lots of sunlight, we get ten to twelve dozen eggs per day. In colder seasons, when there’s less light, we collect fewer eggs. We were down to one and a half dozen per day last January.

Our chickens squawk — as do the ducks. That’s a good sign. They communicate. Many animals live lives of stress. They don’t see humans as helpful or caring. But here, we’re affectionate, and so are they. Their responsiveness is part of the beauty of the human-animal relationship. Temple Grandin and others in livestock will say that herd animals in distress from predators do the stiff upper lip thing, because that’s a survival skill. Ours are happy animals. Where animals are produced on a large scale, this is not the case.

Our goats are largely female. After kidding, all the boys are sold.

Most of the others will be sold, too — as pets and companion animals. People who buy goats and chickens usually have a couple of acres. We have Nigerian Dwarf goats, about the size of Labradors. Children love them. We sell to families looking for pets — to help teach their children responsibility. People come to the farm to buy a goat, and it’s like picking out a puppy. We never sell a single goat to people. We sell pairs. Goats are herd animals. They need connection. Our babies are super friendly and sweet, because we bottle feed them. People take them home in their own trucks. Our babies are used to people; they’ll fall asleep in your lap. It’s usually an easy adjustment when they go home with a family."

Tammy now teaches a free goat-care class once a month. She enjoys it. Tsochen Khandro initiated the idea, and the class is now part of the farm’s educational program. The farm holds many events for children, families, and adults. There are tours, art projects, poetry readings, and games on market weekends.

The Estate Manager

B. Love, formerly known as Rob Davis, is the estate manager. “B. Love” is his Dharma name, given to him by Traktung Rinpoche. B. Love defines his job as “essentially the grounds-keeper and gardener.” He also takes care of produce and helps display much of the community’s ritual and fine art. He trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and worked at several museums, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, where he spent thirteen years. (The sublime Buddhist murals he painted at White Lotus Farms were featured in CW Issue 50, Spring 2012, in the article, “Drawing the Buddha’s Sublime Form — Buddhist Artist Rob Davis on Internalizing the Image of the Buddha in Tantric Art.”)

““I am deeply grateful for the depth, simplicity, and richness of the life here.””

He attributes to Tsochen Khandro much of the satisfaction he gets in living at White Lotus Farms. He sent me this explanation:

"Khandro works with all of us who live on the gar and work in the businesses. She meets with us every week during the main season. The mindfulness we aspire to in our labor includes our interaction, service, care, and kindness to every being we are with. Khandro works with us with incredible insight and clarity. I spent years in therapy. If I have a problem with someone here, we can have one meeting with Khandro and suddenly the problem is understood and dealt with in a way that is inconceivably swift and simple. It is Her Great Skill. She does this with all of us. She teaches Dharma formally, but she really teaches us by demonstrating what in Mahayana is called the Six Paramitas. Her equanimity in all situations is always surprising and transformative. Rinpoche has said numerous times that this community only exists — and in the way it does — because of Khandro.

The goal we have here is not just to support ourselves, but to be productive — while serving beings with wisdom and kindness. After thirty years in the work force, all I can say is that Khandro has made White Lotus Farms not only the most extraordinarily productive place I have ever worked, but the most rewarding and joyful. It is easy to believe in Buddhist principles of self-awareness and mind training, but it is nearly impossible to just stop and be mindful, on your own. It is the reason we are very teacher-focused in Vajrayana. They teach us the concepts, but they create circumstances and demonstrate ways in which mindfulness can be applied at the level of being; they show the grace of it. Khandro truly makes this possible. Here, there is a tremendous amount of joy and humor — even in dealing with difficulties.

It should also be mentioned that in our practice we all use the sacred music that Khandro records. Much of the interior design and Feng Shui that these buildings have come from her aesthetic touch. There is an elegance in everything she does. She transmits something very intangible — about compassion and wisdom. I am deeply grateful for the depth, simplicity, and richness of the life here.

Khandro, by the way, also has a fun, quirky side. We have lip sync battles, and Khandro will often do Justin Bieber. She even dresses up like him. She does his songs perfectly. And we play a lot of board games — especially after group dinners or on holidays. She loves to win, but she also seems really happy when other people win. And sometimes she gets an accent going! I’ve heard her sustain a Russian accent for a week. The playfulness here is amazing! She’s always learning new things, too. Recently she’s been painting and playing the tabla drums."

Several people from outside the community also contributed their thoughts on Tsochen Khandro. At the request of these long-standing friends of hers, their testimonials will remain pseudonymous.

Jack offered this: “Katie and Traktung have created an exceptional meditation community. Their inventiveness and originality and their unique perspectives are matched by their devotion to the community. Intellectually, Traktung is quite a force.”

Leah speaks fondly of Tsochen Khandro, though they have not seen each other in a couple of years. “I’ve always loved Katie’s candor and humor — particularly as it relates to her family and children. She’s one of the most honest people I know. She’s open and sharing, with depth and capacity.” Tsochen Khandro and Leah each attended the birth of the other’s first child. Leah also speaks fondly of the “sacred dancing evenings” that Tsochen Khandro and Traktung Rinpoche held, often at the Friends Meeting House on Hill Street. Those events no longer happen, at least not for the public, but both Jack and Leah remembered how “wonderful” those dancing sessions were.

For the dancing sessions, four or five members of the Tsogyelgar community would play music, and 20 to 45 people would dance. There was eye contact and lots of connecting with people. Asked to describe the dances, they explained that it was like Sufi dancing. It combined chanting with body movement, sometimes slow, sometimes fast, but always in motion. Someone would introduce the dance, explain and demonstrate the movement, and everyone would learn it together. They moved slowly until people had it: turn, bow, arms up, arms down. It might take five or six minutes for everyone to have learned it. Then the music would begin, the instructions cease, and the dance was underway. “It was a natural high. It was heart-opening.”

It is clear that this community of Buddhist practitioners is earnest, devoted, and determined to live according to the path they chose. It’s not easy. Tsochen Khandro describes it this way:

"Our community is small because those who study with us have to be like the Navy Seals of Buddhism. Students here begin and end their days with meditation practice. Normally, they do two or three hours of practice a day. On retreat, they practice eight to ten hours a day. We all put Dharma at the center of our lives.

For decades of my life, while raising young children, I awoke at five a.m. so I could practice before they were awake. And I practiced as soon as they went to bed. I went on a solitary retreat every year for a month once my first daughter reached the age of five. I had no contact with the world, including my family. We had an agreement that I would not be contacted unless my daughter was hospitalized and needed me. But if any member of my family were to die, I would not learn about this until coming out of retreat. I had to let go of everything to go into retreat, not knowing if it would still be there when I came out. This was very good for my practice."

All this is impressive, even laudable. But I was still confounded by some of what I heard. Initially, for instance, when I asked Tsochen Khandro about her life’s daily routine, she responded: “Well, let’s start with this life.” Her husband is understood to be Traktung Rinpoche Yeshe Dorje, the self-proclaimed reincarnation of Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje, a Tibetan mystic who lived in the 19th century. When I asked her whether she believes this to be true, she grew impatient. “He is the most brilliant, fascinating, fiery, passionate person I know.”

She added, “He can be confrontational, but he is loving.” She then explained that the function of a Bhakti oriented master is to seek the truth and interfere with patterns of delusion, adding, “And he plays whack-a-mole with delusion,” meaning he directly confronts people who dabble in denial or any other form of self-deception.

I told her that I had gone back and read a previous interview with her and her husband (in a 1998 issue of the Crazy Wisdom Journal, available at this link bit.ly/crazywisdomInterview1998 at the Crazy Wisdom Journal archive). The interview included their comments about having studied with the Indian guru Rajneesh (now more than 25 years ago). I mentioned to her that I’d read about his scandalous sexual behavior at his Oregon commune and that he was wanted by the Indian government for unpaid back taxes. Tsochen Khandro wasn’t keen on having me rehash these issues first raised in an interview 18 years ago, an interview which is now almost like ancient history. “Osho [Rajneesh] had a mischievous sense of humor,” she said, dismissively. “The sex stories were overstated and simply wrong.” When I ask about the stories that swirled about him — that he didn’t pay taxes in India or in the U.S., that he was a womanizer, that he lived in the lap of luxury while his sycophants worked themselves to the bone for him, that he was deported — she said: “Gossip and rumors. People didn’t understand. And it’s not about defending Rajneesh, though it’s true that I will not say anything bad about him as I still love and respect him. It makes no difference to me what people think of him.”

Tsogyelgar shrine room, which contains the largest tantric murals in North America created by B. Love (Rob Davis) and Traktung Rinpoche. For more detail, visit: tsogyelgar.org/art-galleries/2016/1/7/the-shrine-room-at-tsogyelga

Yet one needs only to Google “Rajneesh” to find published stories of his sexual abuse of students. His reputation suffered. He was, eventually, deported from the U.S. for non-payment of taxes. I was struck by how she seemed to be somewhat of an apologist for him, but my views were expanded after I met again with Traktung Rinpoche.

Soon after that meeting, when I arrived at the farm to speak with him, he raised the issue of strange behavior, referring obliquely to my previous inquiry regarding Osho. In doing so, he went on to teach me about the Buddhist meaning of “Crazy Wisdom.” The term refers to “a teacher who doesn’t always act within the boundaries of social appropriateness.” Certain teachers will behave in ways that seem crazy to protect and teach their students. Teachers, said Traktung Rinpoche, create circumstances in which other people can grow. This is called “the poetry of circumstance.” Such pedagogy can be uncomfortable, but provocative acts can promote wisdom. Traktung Rinpoche offered two classic examples of crazy wise teachers (crazy wisdom).

- A sage walks down a street and sees a man sleeping under a tree. He watches a poisonous spider enter the sleeping man’s mouth. Instead of nudging the man awake and telling him about the spider, risking the chance that it might bite or be swallowed in the process, the sage startles the man awake and shoves his finger down his throat. The man throws up. When he sees the spider in his vomit, he understands that the sage just saved his life.

- A Dharma teacher is asked by a student what it takes to achieve enlightenment. The teacher grabs him, drags him outside to a well, holds his head under water, and just as the student is about to pass out, the teacher pulls him out. The teacher then asks him what he thought when she grabbed him and pushed him into the water. He responds: “I thought you were crazy. Then I stopped thinking; I just wanted to get out.” The teacher says: “When you want enlightenment as much as you wanted to breathe, that’s when you will achieve it.”

Tacitly referencing Osho again, Traktung Rinpoche acknowledged that womanizing is never acceptable. But he pointed out that sometimes, for a higher purpose, strange, mind-bending, disturbing, and even brutal measures must be taken to lead a person to enlightenment — or to save that person from danger.

“Crazy Wisdom: “a teacher who doesn’t always act within the boundaries of social appropriateness to create circumstances in which other people can grow.””

My conversations with Tsochen Khandro, and later with Traktung Rinpoche, were lively, warm, and wide-ranging. Each is charming, knowledgeable, and engaging. They can hold forth at length, but each is equally interested in listening. They speak without inhibition about paranormal events in their lives, but these experiences are very real to them. They have consequences. Tsochen Khandro’s childhood certainty, for instance, that she was destined to meet a certain someone who would be her life-changing soul mate, really happened. She also talks about “Dream Yoga,” a familiar experience for her, and a tantric experience. It is a trance-like state of being, in which one is conscious of dreaming even while asleep and dreaming. In “Tibetan Dream Yoga,” nothing harmful can happen, and fear is erased, as long as one recognizes that this is a dream. In dream yoga, fire won’t burn; the dreamer can control it.

For Tsochen Khandro, dreams of this nature remain powerful symbols of what she must do and when. She also has a sixth sense about people, a quality that is confirmed by those who work with her. It may sound odd to speak of disputes in a Buddhist community whose spiritual quest is inner peace and interpersonal harmony, but even Buddhists are mortal. Being human means we make mistakes, misconstrue, miscommunicate, and otherwise lay the groundwork for quarrels, however much we may abhor that state of being.

Traktung Rinpoche calls himself an empiricist. “I believe in verifying through empirical experience,” he said. “I never believe without checking.” That applies even to everyday science. “I don’t have to believe water boils at a certain temperature, I can test it on the stove.”

Asked how he knew he was the reincarnation of Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje, Traktung Rinpoche described the memories that confirmed this. He has memories from a time when he was “a nomad, a farmer with sheep. I remember chanting, the sounds of bells.”

He became interested in religion at an early age. He begged his parents to take him to church. They wouldn’t. So his grandmother did. She was a Southern Baptist. Her grandson listened to a hellfire sermon that alienated him. He felt religion, he said, but he never went back to church after that. When he was twelve, his parents thought they should read the New Testament to their three sons. They read for two nights. On the third night, Stuart, the youngest, took it to his room and read it thirteen times.

"I thought: this Jesus is everything I’m feeling. He was a life of pure love and giving, self-sacrifice for truth and love. He forgave the people who killed him! This was my dream — to be like that."

Years later, Traktung Rinpoche’s Buddhist friend, Lama Yonton, met him when he came to him from Tibet; his wife had seen a picture of Traktung Rinpoche in a published article and said, “I have to go see this man.” She remembered being Traktung Rinpoche’s student in a former life. So they came. They spent three months. At dinner the first night, Lama Yonton looked across the table and told Traktung Rinpoche: “I remember you, too. We were both reincarnated as children of the same person.” Traktung Rinpoche was impressed. “He was my older brother in a former life,” he told me. “I always wondered whether my ‘daydreams’ were real.”

There are more such stories. Lama Yonton was looking for a certain castle in a remote area of Tibet. It was the castle of a famous historical figure. Traktung Rinpoche told him where to find it. “I’d remembered this place — from several hundred years ago.” Traktung Rinpoche said that his directions proved accurate.

Traktung Rinpoche spent a great deal of time rendering sacred Tibetan Buddhist writings into English — even though he does not speak the language. He worked with a translator. He wanted to find a certain section. His translator couldn’t find it. After telling her to check the middle of the text and look for a section called “Flames of Lapis Lazuli,” she found it. “How did you know?” she asked him. “Because I wrote it!” he replied.

He now takes these experiences in stride, having grown accustomed to his own and others’ shock. “Over time,” he said, “when enough of these things occur, you begin to believe it really happened. The other possible explanation is that I’m part of a living myth, in a Jungian sense — a keeper of the collective unconscious.”

###