Interview by Julianne Linderman

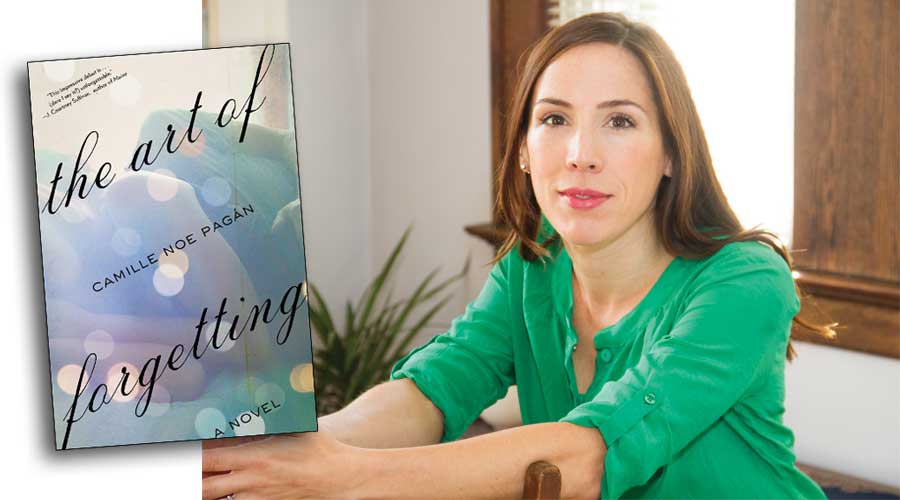

Camille Noe Pagán, age 33, is an author and journalist. Her successful first novel, The Art of Forgetting, was published in 2011 by Penguin. The book was met with considerable acclaim from readers and critics, with the Chicago Tribune calling it “a quietly compelling literary debut . . . about the power of friendship and the importance of forgiveness.”

Camille lives in Ann Arbor with her husband, JP, and their two young children — Indira, 6, and Xavier, 4. Raised in Dearborn, she attended the University of Michigan and studied English. Upon graduation, she attended the six-week Radcliffe Publishing Course at Harvard University, which propelled her into her career as a writer. After the course, Camille moved to Brooklyn, where she worked as a health and nutrition writer for nearly a decade (writing for such publications as Glamour, Fitness, and Women’s Health). In August 2010, she moved to Ann Arbor with her family. Her next novel is in the works, and she continues to be a regular contributor to national magazines in the health/nutrition field.

Recently, I met with Camille to talk about her book, other writings, and life in Ann Arbor. Meeting with her was a pleasure; having devoured The Art of Forgetting in two or three sittings, I was certainly eager to get the inside scoop on how it all came about.

The Art of Forgetting explores the close friendship between Marissa Rogers and Julia Ferrar, two young women who are pursuing their career dreams in New York City a few years after graduating from the University of Michigan. But when Julia suffers a traumatic brain injury after a sudden accident, her memory and personality are drastically altered, and both women’s lives take unexpected turns. As the plot unfolds in this thoughtful and intelligent book, so do deeper themes about friendship and self-acceptance.

***

Julianne Linderman: Can you tell us a little about how you got the idea for The Art of Forgetting?

Camille Noe Pagán: I’m a journalist specializing in health, nutrition, and wellness. Before I wrote Forgetting, I knew about brain injury because news outlets were increasingly covering it, particularly in regard to football players’ and troops’ injuries. It wasn’t until I began writing a Women’s Health story about brain health, though, that I realized just how prevalent traumatic brain injury is in young women. The fact that one seemingly small event — a fall, a car accident, a sporting injury — could affect a person’s personality, possibly forever, was profound, and I wanted to explore the topic in a fiction format.

“The fact that one seemingly small event — a fall, a car accident, a sporting injury — could affect a person’s personality, possibly forever, was profound, and I wanted to explore the topic in a fiction format.”

Julianne Linderman: Has it always been a dream of yours to write fiction? How long have you been writing fiction?

Camille Noe Pagán: I’ve been writing stories since I could hold a pencil; my mother often sends me little “books” or stories I wrote as a small girl, which she’ll find tucked away in drawers and boxes. Winning a young author contest in third or fourth grade was one of the highlights of my childhood, and I think I always knew, deep down, that I ultimately wanted to write books.

Even so, I attended college on a full academic scholarship, and I think because of that, I felt a lot of pressure — most of it internal, no doubt — to do something “practical.” I took creative writing classes during college, but initially planned to be a physician or something similar, like a researcher. When it became obvious that I was a far better writer than science student, I decided to go into publishing. That was a very good decision, as working as a magazine editor and later a journalist gave me the ability to earn a living doing what I love — writing.

I didn't try my hand at writing novels until my late twenties. Forgetting was the first novel I completed start to finish. After its publication, though, I wrote several other novels that I really didn’t like, and didn’t attempt to sell.

“Winning a young author contest in third or fourth grade was one of the highlights of my childhood, and I think I always knew, deep down, that I ultimately wanted to write books.”

Julianne Linderman: How did the title come about?

Camille Noe Pagán: The title came to me after I wrote roughly half the book. It more or less just popped into my head, but I knew immediately that it was just right for this story — it touches on the brain injury aspect of the story, but also on the fact that Marissa must ultimately choose whether or not to move past the issues she has with her old friend. Publishers often suggest new titles for novel manuscripts. I was thrilled when Penguin agreed that The Art of Forgetting was the right title for this story.

JL: I found the book to be an inspiring tale for women about discovering healthy self-esteem. Little by little, Marissa Rogers, the main character, shows signs of becoming more assertive and less self-critical. Is this something you hoped readers would take away from the book?

CNP: Thank you! Many readers assume that the character of Marissa was inspired by my own experiences. While there are parts of me in her — and all of my characters, really — I was inspired to write her after interviewing literally hundreds of women over the several years I worked as an editor. It struck me that no matter how different these women were — unique jobs, life circumstances, personalities — they often shared a common issue, which was the struggle to accept themselves for who they are, rather than who they want to be or who society tells them they should be. As with the topic of brain injury, I wanted to examine this struggle in fiction.

JL: And it seems that through Marissa’s character, this struggle is conveyed most strongly. It was refreshing to read about a young woman, nearing 30 years old, who, despite having a fantastic job as a magazine editor in NYC and a great relationship, certainly does not “have it all together” beneath the surface. Can you comment more on how you developed her character and Julia’s?

CNP: Fiction is such a weird process that it’s hard to explain how I develop my characters; for me, the more I write, the more I “know” my characters, and that allows me to go back and edit early drafts of work to make them even more true versions of themselves.

That said, both Marissa and Julia came to me quickly and organically. I knew that I wanted to write a protagonist who struggled with real issues that affect many women. And I wanted her best friend to be the woman who looks like she has it all, but who, in reality, also struggles with self-esteem issues and doesn’t have it all together.

“I am a naturally curious person, and every new story I write gives me the opportunity to learn something new.”

JL: You mentioned that after the book came out, many readers wanted to talk about the “love triangle.” Can you briefly describe the love triangle, and why readers may want to talk about it, for those who may not have read the book?

CNP: The love triangle you’re referring to is between Marissa, Julia, and Marissa’s college boyfriend, Nathan. When Julia discovered that Marissa and Nathan were dating, she was jealous — and also attracted to him. So she asked Marissa to let him go, and in spite of her better judgment, Marissa agreed. Now, a decade later, Marissa and Julia both reconnect with Nathan, and the reader is left wondering what the outcome will be. I think so many readers related to this part of the story because we all have someone from our past that we wonder about — a person about whom you can’t help but think, “What if we’d stayed together?” or “What if we got back together?”

JL: Part of the book took place in Ann Arbor and part of it in New York. Can you tell us more about these settings? Are there particular things about Ann Arbor that you felt would suit the book well?

CNP: I spent my twenties and very early thirties in New York, and knew I wanted to set the book there. But Marissa and Julia needed to have a “home base,” and Ann Arbor instantly came to mind; it’s such an idyllic college setting, and many of Marissa’s flashbacks are set during her time at the University of Michigan. Interestingly, I came to visit Ann Arbor a few times while working on the first draft to double-check my research, so to speak, and ended up liking it so much as an adult (versus when I went to college here) that my husband and I ended up moving here from Brooklyn at the end of 2010.

“Some of my most vivid childhood memories center around books: trying to recreate The Egypt Game with a friend; turning my dolls and figurines into different characters from The Chronicles of Narnia.”

JL: Are you from Michigan? Could you tell us a little more about your upbringing? Perhaps share an interesting story or two from your childhood?

CNP: I grew up in the Detroit area. My mother encouraged my sister (who is less than a year younger than me; we grew up almost as twins) to read as much as possible, in part because my mother isn’t a fan of television! Some of my most vivid childhood memories center around books: trying to recreate The Egypt Game with a friend; turning my dolls and figurines into different characters from The Chronicles of Narnia. I love the idea of writing children’s books and may try that next.

JL: You mentioned earlier that you felt some internal pressure to do something “practical” when you first attended college. How did your path shift and what inspired you to become a writer?

CNP: I’ve always been very interested in health; my own family has been affected by numerous health conditions, like rheumatoid arthritis, Type I diabetes, depression, and so on. During high school, I thought it made sense for me to channel my health interest by becoming a physician. But in reality, it was evident from my very first semester at U-M that I was much better at writing than I was at science.

I did take science courses, though, as well as a lot of psychology-focused work, and during my senior year, I worked in a cardiology lab at U-M’s hospital. During that time, my supervisor —this really wonderful cardiologist, Lori Mosca, M.D., who went out of her way to mentor the students who worked for her — said, “You know, Camille, I think you should consider combining your writing ability with your interest in medicine and pursue a career in health publishing.” That was so important, because it made me realize that I could really have a true career in writing, which is what I not-so-secretly loved to do. I attended a post-graduate course in publishing, then landed my first job as a junior editor at Fitness magazine. I think it was only natural that I would look at a health topic in my first novel; though later fiction projects have been less health-centered.

JL: Can you tell us a little more about your journalism career? What do you enjoy most about journalistic writing?

CNP: I studied English and Native American literature at U-M. After college, I attended that post-graduate course in publishing at Harvard, then moved to New York City to work in magazine publishing. After serving as a magazine and online editor for several years, I became a full-time journalist in 2004 (I am self-employed, through a small company that I own). There are so many things I love about working as a journalist. I am a naturally curious person, and every new story I write gives me the opportunity to learn something new. Self-employment also allows me a great deal of freedom. I keep regular hours — and yes, I get dressed every morning instead of working in my PJs J — but if I want to go on vacation or take a morning off to volunteer at my daughter’s school, I can. It’s great.

JL: Was there something in particular that made you want to study Native American literature?

CNP: My father’s family is part Native American, but (for many complicated reasons that I can’t do justice in a small space) my grandparents and great grandparents didn’t embrace their heritage, and were not tribal members. Literature was initially a way for me to understand this, and explore the history of Native people in the U.S. That initial interest grew into a true appreciation: I love the work of Louise Erdrich, for example, and of Betty Bell, an author and professor who mentored me in college.

JL: Do you ever experience “writer’s block”? What types of things do you do to find inspiration again?

CNP: I don’t get writer’s block, really, but I think this comes from years of working on deadline. If you want to get paid (or, when I was working in an office, not get fired!), you turn your work in on time. When I work on fiction, I give myself a daily word count, and I stick to it most days.

Sometimes the work isn’t good and has to be scrapped, but at least I have a draft to work with, and that means I’ve already done the hardest part.

Inspiration isn’t an issue, either, really. It’s more like I have so many novel ideas that it’s tough to know what to work on next! I keep notebooks full of them, and usually the best one bubbles to the surface in my mind, and that’s what I’ll start on.

JL: The task of starting a novel seems like it would be the most difficult (to me at least!). Do you find this stage of the writing process difficult, or no?

CNP: Oh, not at all. I could start a million novels; the tough part for me is the ending. I usually have an end in mind when I start, but getting the rhythm of the novel right — that is, having the story unfold naturally at the right pace — is tricky, especially in the last third of the book. I usually write the first two-thirds of a story very quickly (often in just a few months), then slow down at the end.

JL: What are you working on now, if you’re allowed to say?

CNP: I just wrapped up a book about a woman whose life falls apart in a single afternoon, and how she attempts to come to terms with that disaster by running off to a fairly remote Caribbean island. It's called Life and Other Near Death Experiences.

JL: Has it been purchased by a publisher? Or is this still in the works?

CNP: Lake Union (an Amazon publishing imprint) recently acquired the book and is publishing it in October 2015.

JL: I’m also curious about how you find time to write — as a mother of two young children, I’m sure you are kept quite busy!

CNP: The kids aren’t the hard part; the full-time job is! My children are in school or preschool most of the workday, but during “work hours,” I primarily work on journalism. I write fiction at night and on the weekends, and occasionally squeeze it in on slow workdays. It’s sometimes crazy-making, but I also find that I’m more productive when I have less time. Knowing I have an hour to get a chapter done eliminates the temptation to browse the Internet or answer email.

JL: In addition to writing, you’re also doing some interesting work at Burns Park Elementary School, is that right? Can you describe more about it?

CNP: Burns Park has a relatively new principal, Chuck Hatt, who’s fantastic. Many Burns Park parents have asked him to take a fresh look at the school’s nutrition policies — not just school lunches but also snacks, and how holidays and birthdays are celebrated. With this in mind, Chuck formed a committee made up of interested, health-focused parents and faculty. This year, we’ll begin looking at (and hopefully improving!) the school’s nutrition policies so they’re more in line with what recent research has shown about the connection between healthful food and excellent academic performance. Nothing’s set in stone, but one neat thing we’re talking about right now is the idea of healthy competition — that is, studies show that when kids compete with each other to see who can eat the most fruits and veggies, they consume far more fresh produce than they would otherwise, without feeling like they’re being “forced” to eat nutritious food.

JL: What neighborhood do you live in? What do you like about living here?

CNP: My family and I live in Lower Burns Park. As I mentioned, my husband and I moved here from Brooklyn in 2010, after about a decade there (save a few years in Chicago), and our daughter spent the first few years of her life there, in a great neighborhood called Carroll Gardens. When I became pregnant with my son, who is now four, we realized we wanted more space, to be closer to at least one side of our family, and to live in a community where good schools were a given. We often visited Ann Arbor when we came to see my family (who still live in the Detroit area) and decided pretty spontaneously to look for a house here.

Many thanks, Camille!

Related Content:

To liken Book Suey to an average bookstore would be akin to calling Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein “the boy next door.” It’s missing all the other crucial pieces that make Book Suey a must-stop destination—sure, you can come in for a book, but you can also stop in and read a poem during open-mic night, attend a writing workshop, sell a physical copy of your writing, and more. Think of Book Suey as a bookstore with a side of DIY ethos, a pinch of mischief, and the kind of vibes that make you want to stay a while. Maybe even forever, as co-owners Cat Batsios and Elijah “Eli” Sparkman will explain.