By Sandor Slomovits | Photography by Fresh Coast Photography

Susan Beckett is the publisher of Groundcover News, a street newspaper sold in Ann Arbor and throughout Washtenaw County directly by vendors – many of whom are experiencing challenges related to poverty. Groundcover’s stated mission is: “Creating opportunity and a voice for low-income people while taking action to end homelessness and poverty.” At two dollars per issue, the monthly paper features articles highlighting homelessness, poverty, and other social issues, but also includes poetry, Sudoku, crossword puzzles, and recipes. Unique to such street newspapers like Groundcover, it also contains stories by and/or about its vendors.

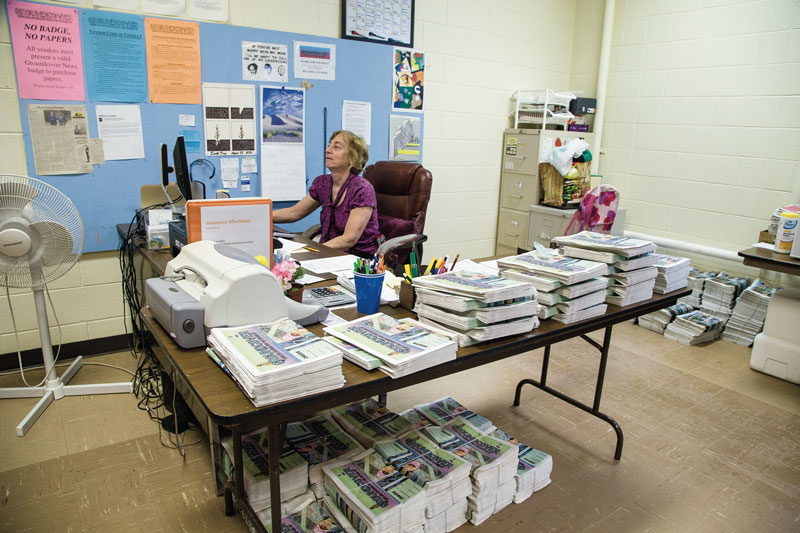

Beckett is trim, wears her hair short, with a straightforward, matter of fact manner, but also has a vivid, entertaining way of talking about the history of the paper and its vendors.

We talked in Groundcover’s office in the basement of Bethlehem United Church of Christ, in downtown Ann Arbor. I began by asking how long she’s lived in Ann Arbor, and what brought her here.

“Groundcover’s stated mission is: “Creating opportunity and a voice for low-income people while taking action to end homelessness and poverty.””

Susan Beckett: I grew up in New Jersey, about twenty miles west of the Lincoln Tunnel, met a couple Midwesterners when I worked at summer camps in the Adirondacks, and could not believe there were such nice people in the world.…

Sandor Slomovits: Having grown up in New Jersey? (Laughter.)

Susan Beckett: One of them was going into her senior year at U-M and she said, “Have you visited colleges yet? You need to go visit colleges. You should come visit me. You can stay with me in the Lenny Bruce Co-Op.” So I did and I said, “This is where I want to be.” So I came here to go to college and I never left.

Sandor Slomovits: When was this?

Susan Beckett: I started in 1971. I didn’t graduate for a really long time. I was a creative writing major and sometime around the middle of my junior year I realized that I just didn’t have it in me to be a starving artist. I dropped out for a semester, talked with one of my wise uncles who said, “You should take some technical writing and computer courses because there’s plenty of jobs out there for people with those skills.” So I went back to school, but wasn’t able to graduate, and my parents wisely said, “You’re on your own now.”

I got a technical writing job at Comshare and wrote documentation for accounting programs, boring things like that for about a year. Then they needed somebody to document the operating system and because I’d taken enough computer courses to be able to speak to the technical people and read all the code, they said, “How about if you do it?” That was a long project – about a year and a half – and when I finished, the manager of the operating systems department said, “Now I want you to come work for me.” I said, “I’m not that good a programmer, I just took a few courses.” He said, “That’s OK. You understand how everything fits together, and that’s what I need more than anything.” So I spent the next ten years doing computer programming.

Sandor Slomovits: You got into computers early.

Susan: Yeah, pretty early, particularly being a woman working on operating systems. I was one of several actually at Comshare. They were a pretty progressive place. I eventually got married and really wanted to have children, and they weren’t coming, so I started back to school to get certified to teach elementary education. And Comshare went through hard times, I got laid off, worked at a couple different places, had a miscarriage; eventually, though, I had my daughter. Three weeks after she was born was my last day of programming. I finished up getting certified and then just enjoyed having my daughter. Couldn’t get pregnant again, and then when she was about two I took her to the Sunshine Special, a nursery school on Scio Church Road... And when she was two and a half she said, “I want to go full time.” (Laughter.) And I said, “Well, your friends have to go full time because their parents are working.” And she said, “Well, get a job!” (Sustained laughter.)

“One of the things I found out is that people have a great desire to write and to be heard, but their lives are chaotic enough that there are very few that actually follow through with that.

”

Sandor: Out of the mouths of babes.

Susan: Yeah! I said, “OK, fine, I’ll go do my student teaching. I’ve been waiting till you go to kindergarten, but if that’s the way you feel about it.” So I started student teaching that summer and then immediately got pregnant again. (Laughter.) And my son, unlike my daughter, did not want me to get a job. He wanted to just putz around with me. “It’s fine to go to nursery school a couple days a week, but that’s enough for me.” So, I did some substitute teaching on the days he was at the Jewish Community Center pre-school. I did a lot of substitute teaching, mostly in my kids’ schools, which was great ‘cause I got to know everybody.

And then my mother passed away, kind of suddenly, and I just sort of went catatonic.

Sandor: When was that?

Susan: December of 2009.

Sandor: How old were your kids at that time?

Susan: They were grown, twenty and seventeen. I just kind of lost all initiative. If somebody asked me to do something, I’d do it, but I just didn’t generate anything on my own. And somebody from Temple Beth Emeth, where I was on the social action committee, said, “There’s this meeting of the Religious Coalition for the Homeless that Ron Gregg is organizing, and we need somebody to go, and can you go?” Of course the answer was, “Sure I can, because I’m not doing anything else!” (Laughter.) So I went.

The summer before that my daughter had worked out in Seattle for Grassroots Action, where you solicit signatures and money for the ACLU, environmental causes, et cetera. I visited her while she was out there and, because I had a car, she kept saying, “Let’s go to the store.” So we were in and out of the store multiple times a day it seemed, and every time we went in or out this guy yelled “Real change” at us. And finally I said to her, “Why does he keep saying ‘real change’? Does he think we have slugs or something?” And she started laughing and said, “No, that’s the name of our street paper.” She explained to me what it was and I bought a copy and I thought, “What a great idea!”

So, when I came back to Ann Arbor, I talked to my fellow activists and they all said, “Well, that is a great idea. But, you know, Seattle is a big city, Ann Arbor is not. You couldn’t make it work here.” I got that same response from ten people and I said, “OK, just let it go.” (Laughter.) …Until this meeting with the Religious Coalition for the Homeless. It was pretty clear the impetus for the meeting was to try to get together the resources to have a 24 hour wet shelter, which was going to cost millions of dollars, and at that time we were already deep enough in the recession that everything was being cut back. There were not millions of dollars to be had anywhere.

““Yeah, they don’t know where to start, they don’t know the people, they personally have no commerce with the people who need that kind of help. Everybody’s a little afraid to just go up to somebody who’s holding a cup. But Groundcover provides a medium of exchange in many ways.””

So at one point I said, “I know this isn’t going to solve all the problems that have been laid out, but it will solve some of the problems for some of the people.” And I told them about the street newspaper. And several people said, “That sounds interesting.” Then the end of the meeting came and it was time for people to say who was going to do what, and nobody’s hand went up, and I said, “I’ll look into finding out about a street newspaper.” And several other people, including Sandy Schmoker, who’s been a volunteer since the beginning, said, “Well, I think that’s a good idea and I’ll help you.”

At that time there was a coalition of American newspapers, and I contacted them and found out that they had just hired a guy, the first time they had a staff person, who would help get a paper started. He said, “Here’s the PDF of our manual for how to get started, and lucky you, a paper just started in Toledo three months ago, and so they can show you the ropes.” He gave me contact information for the person down there. I called and Amanda Moore, now Amanda Zuehlke, said, “Oh yeah! I love Ann Arbor. You can definitely make a paper work there. If we can do it in Toledo, there’s no question you can in Ann Arbor. You have such a vibrant downtown. How about if I come up and meet with you, because I love to come to Ann Arbor.”

She came up and met with me and Sarah Heidt from the Religious Coalition for the Homeless. We met at one of the old Borders Bookstores and the first thing she did, she went to all the free magazines, and said, “OK, in the environment you’re in, you’re going to have to have at least some color, probably want a twelve page format, just call up any of these guys and find out who does their printing, find out who the local printers are…” She just went through everything with us, what we would need to do. She called the next day and said, “I talked with the person who gave us our startup funding, and he’s going to do the same for you.” One Matters is going to give you a check for $1,000 dollars, and it’ll take no more than $800 to print your first edition; and then you can use the money you get from that, plus the extra couple hundred to print your second edition, and then you should be off and running. That’s all the seed money you’ll need.”

This all happened at the beginning of 2010, just a few days after that first meeting with the Religious Coalition for the Homeless, and from there, things moved fast. Susan wanted to gauge community interest before going further, and so she made an appointment with Ellen Schulmeister, the Executive Director of the Delonis Center. (The Delonis Center is Ann Arbor’s homeless shelter and the location of the Shelter Association of Washtenaw County, which provides housing and other services for between 1,300 and 1,500 people experiencing homelessness each year.) Susan and Ellen were to meet at Sweetwaters Café, but Ellen was running late. While Susan waited, she saw an acquaintance.

Susan: We said “Hello,” and he asked why I was there. I told him and he said, “I might know somebody who’d be an editor for you.” I said, “You know we really don’t have any money to pay anybody.” And he said, “She just got laid off because of the recession, and I think she’s looking for something to do. She might do this for you, anyway.” So he gave me Laurie Lounsbury’s contact information. I called her and she said, “Yes!” (Laughter.) (Lounsbury now sings with the local band, She-Bop.)

So I met with Ellen Schulmeister, and she said, “Yes, I think there’s a place for this in the community,” and, “Yes, you can come make a presentation to the people at the community meal.” So Marquise Williams, also a longtime Groundcover volunteer, and I went to the Delonis Center and, after telling them what it was about, passed around a clipboard where people could put their name and if they were interested in writing and/or selling the paper. About two thirds of the people said they were interested in writing, and about a third said they were interested in selling. It was very surprising to me. And as it turns out, some of them have gone ahead and written for us. One of the things I found out is that people have a great desire to write and to be heard, but their lives are chaotic enough that there are very few that actually follow through with that.

Sandor: That might be true of the general population, too. There are a lot of people who’d like to write the great American novel.

Susan: Yeah.

Sandor: And whose lives are not as chaotic, and they still don’t get around to it. (Laughter.)

Susan: Yeah, well some of us create plenty of our own chaos. (Laughter.)

So then we just started having meetings. We contacted all the people who’d signed the clipboard, we put up flyers in a few places, started having meetings over at First Baptist church, up on Washington, organizing meetings — that’s how we came up with the name, Groundcover. We had all kinds of suggestions and that was the one that got the most votes.

We decided we wanted to put out our first issue around the time of the Art Fair, thinking that that would be a good time to spur sales. In retrospect it was not, but our first issue came out in July 2009, and we made it the July-August issue. We printed 5,000 copies; I think we sold a few hundred. (She laughs ruefully.) Then we came out in September, and shortly after that we started printing monthly.

At first, we found our vendors at places like the community meals and the First Baptist dinner on Tuesday nights. Our early vendors were really good about talking to other people and reaching out. And we did presentations pretty frequently. We were going to the breakfasts at St. Andrews at least a few times a week, maybe every day. That was where people could get papers. St. Andrews got us a couple of big bins and a place to keep them. Then, in one of our issues, we put that we were looking for office space, and Bethlehem United Church of Christ contacted us and said, “We have space and it’s something that our congregation is committed to, so come take a look.” They’ve been wonderful to us – it’s rent free, they provide the electricity, cleaning service, the Internet, which we also use for the phone – I mean, really incredible.

I had never been somebody who believed much in destiny, or the hand of God, or anything like that, but this experience was…. I can’t really ascribe it to much else. So much fell into place so fast. You know, in my personal life I tend to try to plan and make sure and organize, but Groundcover, I’ve kind of just operated on faith, that if we needed, it’ll show up. (Laughter.) And it has! (More laughter.) In fact, it’s interesting, we were talking just a couple of weeks ago, people were saying, “We need to get more publicity, we need to get the word out there some more.” And then I saw the email from you. And someone from the Michigan Daily is interviewing one of our vendors and stopped by yesterday…. Hey, I guess we needed it, and it showed up.

****

““By the time somebody gets homeless they’ve pretty much burned every bridge, and people are reluctant to resume contact with somebody who’s likely to be asking for something. So, by becoming independent again, it allows them to repair personal relationships.””

I asked Susan about her childhood and family experiences to get a sense of what may have led to her work, first in computers and later in founding Groundcover News. Her father, who immigrated to the U.S. from Germany when he was thirteen years old, was an engineer who worked on the guidance systems for some of the NASA projects. But, as she explains, it was her mother who pioneered her interest in computers:

My mother went back to school when I was about eleven to learn computer programming. Eventually she became a vice president at Chubb Insurance Company in charge of systems analysis. She was one of the glass ceiling shatterers. But she grew up in the [Great] Depression. Her father died when she was twelve, and they struggled. My grandmother and all the girls knitted to try to make some money. It was always a very big deal to my grandmother. She said, “I never want to rely on a soup kitchen or anything like that again.“ That made an impression on me. I knew how much she wanted to provide for herself in a dignified manner.

And there was more. For the last thirty years Susan has been a volunteer lobbyist with Results, an organization that lobbies nationally for proven low-cost solutions to issues of poverty and hunger. “When I started, there were still 40,000 children dying every day from preventable disease and hunger,” states Susan. “I’ve always been drawn to children and just couldn’t tolerate the thought of kids going through that and parents going through that.…” (Her voice trails off.)

I tell her that I know that none of us are happy to know that there are people out there who are suffering, who are having a very hard time, in some cases needlessly dying, but relatively few of us say, “OK, here is what I’m going to do about it.” She agrees, “People feel powerless.”

So I ask her again what was different for her? What else in her childhood pointed to her saying, ‘I’m actually going to do something’? And she reminds me that her father’s family left Germany to escape from the Nazis, that they were relatively lucky and most got out. “Still it loomed pretty large in my childhood as something I wasn’t going to stand and be passive about. I guess I made a decision back when I was like ten years old that I wasn’t going to be passive.”

****

Susan Beckett: I want to go back to something you said earlier, about how and why so few people actually do something. That’s part of why Groundcover operates the way it does, where it’s sold only person-to-person on the street, because it’s kind of an entry point for doing something. I think one of the reasons that people often don’t do anything, is because they…

Sandor Slomovits: Don’t know where to start.

Susan: Yeah, they don’t know where to start, they don’t know the people, and they personally have no commerce with the people who need that kind of help. Everybody’s a little afraid to just go up to somebody who’s holding a cup. But Groundcover provides a medium of exchange in many ways. And a lot of our customers have gone on to befriend their vendor in many ways. Some great relationships have come out of that. There are parishioners at St. Mary’s who go out for lunch or dinner with some of our vendors, sometimes have them over for dinner. They’ve bought them whole sets of winter outdoor clothes. A parishioner at St. Francis just gave one of our vendors a bicycle so that he can get around better. Tony (a Groundcover vendor) has done yard work and building repairs for several of his customers, and I’m pretty sure that some of Joe’s (another Groundcover vendor) customers have had him do landscaping work, snow removal. Some of the customers, they trust their vendors enough to have them do some of the tasks that they might no longer be able to do themselves. We have another vendor right now who is doing that on a regular basis for an elderly woman; whatever she needs, she just goes over there for so many hours a day.

There is an especially poignant story. There was a little girl at St. Francis who had cancer and Tony, he would write on every paper he sold, “Pray for Mariel.” Her parents were so touched that they invited him to the funeral. It really made a big difference to them. And he was devastated. Even though he knew it was coming, when she finally died, he was devastated.

Sandor: How many vendors have you had over the years, and how many of them are active now?

Susan: We’ve trained about 375. Active right now, we have about thirty-eight.

Sandor: What is Groundcover’s circulation these days?

Susan: I think we sold about 7,500 papers in March, which is an uptick from where we had been [earlier] this year. When we started, our monthly circulation was probably between 1,500 and 2,000. Then it quickly grew. We were pretty much doubling every year. I can tell you when the [Great] Recession broke. 2012 was a great year for us. We were between 9 and 11,000 a month, and growing like crazy. And then the Recession broke in Ann Arbor, and people started getting jobs; and our more capable vendors got mainstream jobs, which was fantastic – it’s what we wanted. But it had (she laughs) a negative effect on our circulation because they weren’t out there selling anymore, and so we dropped down to 5- to 6000. And we’re just starting to climb back up now, which I hope doesn’t mean that fewer people are getting jobs.

Sandor: That’s an example of a good unintended consequence.

Susan: Yeah. When we started Groundcover, I was thinking it was a way to help people get through the Recession, and I was fine with having it end when it was no longer needed. And in terms of the job situation, we’re kind of at that point where there’s enough jobs available for people who are capable of working full-time on a set schedule and don’t have the kind of blemished past that keep people from hiring them. Unfortunately, there are a lot of people who don’t fit that category. We still have 35, 40 people selling for us – people who have severe arthritis or migraine headaches, or they have a prison record. We have one person who is legally blind, and disability doesn’t cover enough for people to actually live. It just covers enough to have an apartment on the edge of Ypsilanti, or a room, maybe, in Ann Arbor. That’s all. And then you have nothing left to eat or anything else. So, until there’s an alternative, I guess we’re it.

Sandor: So Groundcover helps provide these things – food, et cetera – that disability doesn’t?

Susan: Right, but because now the majority of our vendors fit into that category – they’re people who can’t work every day, or they can’t work in the winter because it’s too cold and it aggravates their arthritis – so they sell about two hundred papers a month. That gives them enough to supplement Social Security. Then we still have a few people who are either new to town or have some other impediment to employment, but who work really hard and sell 600 to 900 papers a month.

Sandor: How much does it cost for the vendors to buy the paper?

Susan: Up until April 2017 it was twenty-five cents. Then we raised the cover price to two dollars, and we gave them one month where it was still twenty-five cents, so that they could build up some extra capital for that month, and then the price went up to fifty cents for them. And when somebody new comes, we still give them ten free to start. And sometimes things happen, and they can get up to ten papers on credit. And then there are certain things, like the first Thursday of every month at our social hour, we do a review of the articles in the paper, and everyone who talks about an article gets ten free papers. When the truck comes in with the new batch of papers, everybody who helps unload gets ten free papers. So there are ways to re-capitalize, even if you didn’t save the money…. (Her voice drops to a whisper and she smiles.) Like we told you.…

Sandor: Do you feel Groundcover has been successful, that it has made a difference in lives?

Susan: I guess a lot depends on how you define ‘success.’ We’ve had a number of people who have been reconciled with their families. By the time somebody gets homeless they’ve pretty much burned every bridge, and people are reluctant to resume contact with somebody who’s likely to be asking for something. So, by becoming independent again, it allows them to repair personal relationships. So that’s been a huge success.

Some people, they’re only here for a couple of months, they need to get enough money to buy decent clothes, or buy tools for their trade so that they can get back to work in whatever they were doing before whatever catastrophe struck. We’ve had a number of people who have come out of prison who have been very enterprising and very capable. Whatever it was that they did years ago that landed them in prison, they’d moved beyond that.

We had one man, he was selling Groundcover, he used that to buy a moped, fixed it up and sold it, bought a minibike, fixed it up and sold it, bought a car, fixed it up and sold it. He was doing all of that on the side, now that he had money to work with. He was a very enterprising guy, he just needed startup capital, and eventually he managed to clear up whatever it was that was keeping him from driving a car, and got his truckers license. Last I knew he was driving a truck back and forth across the country, was back to living with his family somewhere in Appalachia… Life was good again.

There was a woman named Peggy, who had leg problems – in and out of surgeries, rehab – but most months she still managed to sell 800 papers or more. She’s now, for the last couple of years, been working as a peer counselor for Avalon. (Avalon is an Ann Arbor-based organization that helps to provide permanent housing for people who are homeless and who have a mental or physical disability.) She still sells papers, mostly just on Sundays, but she’s successfully stabilized her life, and is helping other people stabilize theirs now.

We had a veteran who, when he first started with us, was homeless, really at loose ends. For him, [selling papers] was more having something to do and a reason to talk to people. I think that was more important to him than the money – to experience some success at something. Now he’s gotten housing, he’s built himself a life again. It just helped him through that interim, that waiting, where you have no sense of agency. This is something where they have that sense of agency.

““We had a veteran who, when he first started with us, was homeless, really at loose ends. For him, [selling papers] was more having something to do and a reason to talk to people. I think that was more important to him than the money – to experience some success at something. Now he’s gotten housing, he’s built himself a life again.””

We’ve had a number of people in the construction trades, they don’t have insurance, they get hurt, they need an operation, all their assets get drained, and they end up either losing or selling their tools. So Groundcover has provided a way for them. Some of them have sold Groundcover while they were in a cast. It was something they could still do through rehab. And when they finally are able to work again, they have the resources to buy the tools that they need.

You know, it’s funny, once they get other employment they usually drift away and go right out of my consciousness. (She laughs ruefully.)

Sandor: I’d be surprised if it was not like that. You’re dealing with a lot of people.

Susan: And new ones all the time.

Sandor: Sure. It’s like with teachers – they tend to remember the trouble kids, not the ones who do well.

Susan: Yep. That is so true.

Sandor: What is your sense, what would have happened to these people if Groundcover had not been there?

Susan: We have had a number of people on disability. They were just so depressed, struggling all the time to make ends meet, and falling short and falling more heavily and heavily into debt. That’s the other thing: people used to… go to payday loans, which is really ridiculous for somebody who has no payday. They would consider their Social Security check to be a payday. And so people were getting very heavily indebted. My sense is that there would have been more suicides, quite honestly. People with no way to get out from under – there would have been more suicides and more substance abuse.

Sandor: What comes to mind for me is the Jewish concept of Tikkun Olam, doing good deeds as a way of repairing the world. And also the rabbinic statement, “Whoever saves a single life, is considered to have saved the whole world.”

Susan: You also have to moderate your expectations. Almost everybody now is housed, and some of it is not great, a room somewhere without much in the way of facilities, but it’s a safe place to be. And we still have some people who are getting hotels by the night, but again, they’re not on the streets. And then we have about five people who just this past year got their own place, and they pay for it out of Groundcover money. It’s a big improvement in circumstances. And we’ve been able to get a lot of people hooked up with the kind of counseling they need, financial counseling in some cases.

Every month we do some kind of development course. Sometimes it is advanced sales training, sometimes it is introduction to computers, sometimes it’s more advanced things with computers. We’ve done a financial literacy course several times, we’ve done mindfulness a couple of times, we’ve done anger management a couple of times. We operate from both what we see that they need and what they ask for. We’ve had a number of writing courses. The whole gestalt, I guess. Some people have actually become really accomplished writers, and many are seriously repairing their debt now.

We have a new partner in our financial literacy program this year, the United Way, and they have been terrific. They have an individual coach who meets with people. We do a match savings program, like we have for Kevin Spangler. Kevin is our latest poster child. (Spangler is a Groundcover News vendor who, with the help of his Groundcover sales income, recently started what has become a very successful and fast growing pedicab business called Boober Tours.) If Kevin wants to buy a new pedicab, he puts in $200, we’ll put in $400. So it’s pretty motivating to get involved. But it turns out that really the most valuable part of it is just learning how to manage your money, and then this individual coaching. Kevin said that the coaching has saved him many thousands of dollars. We have a number of people undergoing credit repair. It’s building a foundation for a better life.

Sandor: It’s good.

Susan nods, and then says with a rueful smile, “It’s not fast though.”

###

Gemini, Ann Arbor's nationally known folk duo, will play a benefit concert for Groundcover News on Sunday, February 11, 2018. The concert will be for children and families and is intended to serve as both a fundraiser and to raise awareness for Groundcover News. At press time, the location and time is still TBD. For more information, please visit www.GeminiChildrensMusic.com or www.GroundcoverNews.com.

On February 20 through 23, 2025, ConVocation will celebrate its 30th year as a Michigan convention for magical people. First founded in 1995, ConVocation has been hosted in various hotels around southeastern Michigan before finding its new home in Ypsilanti in 2024. Moira Payne, ConVocation 2025’s Program Chair and President of the Magical Education Council of Ann Arbor, hopes this new home will be permanent.