In 2021, the Legacy Land Conservancy will be celebrating its 50th anniversary.

The Conservancy is a nonprofit, the first certified land trust in Michigan and one of the first in the nation, was originally named the Washtenaw Land Trust (WLT) and was founded in 1971 by a number of people in Ann Arbor to protect the Bird Hills Nature Area and other land along the Huron River. Legacy has grown from that modest beginning to holding 82 conservation easements and seven nature preserves, protecting over 9,200 acres of land in Washtenaw and Jackson Counties.

To learn more about Legacy’s history, accomplishments, and future goals, I communicated with a number of people who are connected to Legacy’s past, present, and future. I began with Diana Kern, 57, who became Legacy’s Executive Director at the beginning of 2019, and Scott Rosencrans, also 57, who is Associate Director of Development and Communications.

Sandor Slomovits: How would you describe the Legacy Land Conservancy, and what you do? What is the most important thing to know about Legacy?

Diana Kern: The most important thing to know is that we are the non-profit for Washtenaw and Jackson Counties that works on conserving land, protecting water quality, agricultural land, and other important natural land, including woodlands and wetlands. Washtenaw and Jackson Counties are our main focus. A few projects are outside that area, but all are along the same four major rivers: the Grand, the Raisin, the Huron, and the Kalamazoo. Our service area covers portions of those four watersheds. We’re helping to make sure that land is conserved properly for future generations, for everyone’s benefit and use.

Scott Rosencrans: We have seven natural area preserves, which is not worked land, but is home to a lot of animal species that are listed as endangered or at risk, and so [natural preserves are] a great step for protecting nature.

Diana Kern: We’re not conserving land within the city limits. We don’t do parks, so any land that we place in a preserve is a natural preserve. It’s woodchipped trails, no paved parking lots, no bathroom facilities—just a natural preserve.

Scott Rosencrans: There’s a similar model within Ann Arbor city limits; for example, our natural area parks, Dolph, Bird Hills, places like that. You won’t see as many way-finding signs or amenities in our preserves, but the concept is very similar.

At the same time, by placing conservation easements on farms where the current landowners want to do that, we’re providing a future for folks who might want to get into the farming world. The easement makes it more sustainable and doable for those interested in farming.

Diana Kern

Sandor Slomovits: How does placing a conservation easement on your property work?

Diana Kern: The land owners still own their land, they pay their own taxes, but they’re restricted per the agreement that we sign—which is called a conservation easement—and that conservation easement places restrictions on that land forever. So if a farmer wishes to place an agricultural easement, he is ensuring that, past himself, that land is never developed—it does not become a Walmart, it’s not subdivided into home lots—it will forever be an agricultural space. The next person who purchases that land will actually inherit the conservation easement, as the easements stay with the land, not with the owners. Whether it’s natural space, wooded lots, wetlands, or farmland, that’s what a conservation easement does. It ensures that the land stays in its natural use.

Sandor Slomovits: Land conservancy has become a nationwide movement. What was it that sparked the movement fifty years ago?

Diana Kern: There were some legislative changes, IRS changes, that allowed for landowners to work with a land trust, which was the name that was used back then, to conserve land. Those changes really came out of a fear that we were going to end up developing all of our beautiful land. So those tax laws which came into effect allowed for non-profits to form that would assist landowners in placing conservation easements. And for some landowners, there’s quite a fair tax benefit for doing this.

Slomovits: Is that the main benefit they receive, that they get some tax relief?

Kern: Some do. Land is appraised at a certain value, and if that land can potentially be used for development of any kind, it has a higher value. Once you remove those development rights, you decrease the value. So, in some cases that provides a tax benefit for the landowner. On farms there are some similar federal programs. If a farmer is going to ensure that the land stays in agricultural production forever, there are federal programs that actually, through us, pay the farmer, and they receive that benefit now. A lot of farmers are land rich and cash poor. They can place conservation easements, and hopefully that gives them some funding to be able to live decently now and or make improvements on their farm. And then they’re also getting the benefit of knowing that their farm is always going to be in agriculture.

There are also many who just come to us and say, “Listen, this land has been in our family for 100 years, and none of my kids live in the area, no one wants the land or the house. I want to ensure that whatever happens to me, that this land is conserved.” So sometimes the easements are done through a living trust; somebody, while they’re still alive, will set up the conservation easement within their living trust, and when they pass, that land is going to be conserved. Whoever it goes to will inherit that conservation easement; they can’t go build on that beautiful 100 -year-old forest.

Slomovits: How did each of you come to this work? What in your childhood, or family history, led you here?

Kern: I was born and raised in Michigan, in Oakland County, Milford-Highland area. I grew up in the country on a dirt road. There’s still a lot of those in Michigan. Growing up in the country, that was part of who I became and cared about. I never wanted to live in a big city. As I grew up, I also watched the community change significantly. The Highland and Milford that I saw when I was growing up are completely different now. And I felt that some of that change took away some of the really wonderful natural aspects of the community. So I’ve always been interested in conserving what I consider to be part of our culture and ensuring that people can have access to and engage with nature. I’m also an avid bird watcher, have been since I was younger, so I care a lot about habitat for pollinators.

I worked for 17 years in the for-profit world and then decided that I wished to leave that world, and since then have been in the non-profit world. I’ve worked for three different non-profits, and this opportunity came around. I was approached by some people, and I said, “Oh my God, this is my dream, to come here.”

Read a related article: In the Heart of the Wood on a Rainy Night—Reflections on Black Pond Woods

Slomovits: What were you doing in the for-profit and non-profit worlds?

Kern: I was in real estate. I worked for one of the largest companies, McKinley, for 17 years. It was great and a wonderful learning experience, and then some things in my life changed, and I was finding if I got up in the morning and I had some of my non-profit work to do, I was super happy, but if I had to get back on a plane and fly to God knows where, I was not happy. So I made a decision that what I really wanted to do was be in the non-profit world. I worked for the New Center in Ann Arbor for ten years, then I worked for about three years for Our Sight, which is the State of Michigan’s eye bank.

Slomovits: What about you, Scott?

Rosencrans: Similar background. My family kind of moved around when I was a kid, but the place I always found myself the most comfortable was running around in the woods, building tree forts, playing in the creeks, looking for crayfish and tadpoles, that was my thing.

Scott Rosencrans

Slomovits: Where did you grow up?

Rosencrans: Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. When I was in my early teens, I worked on a farm that was owned by a friend’s family. We would bale hay every year, we worked in the woods clearing trails—I enjoyed being outside. When I turned 14, I had my first involvement with the environmental world when I became a volunteer for Greenpeace, which at the time was a fairly new organization. I was hooked from there, and since then I’ve always had my hands in serving the greater good, often as a key volunteer, but just as often on staff. And while I was doing volunteer work, I would find a way to make a living in other ways. I was a general contractor here in Ann Arbor, I worked in factories, did a couple of different lines of work. But, back in 2007, John Hieftje (then Mayor of Ann Arbor) appointed me to the Parks Advisory Commission. We also preserved natural areas as well as active recreation parks, and I was on the Land Acquisition Committee as well, and something sort of clicked in me. I hadn’t finished my bachelor’s yet, and I went to my wife and said, “I found the work that I love. It just doesn’t pay me anything.”(Laughter)

Slomovits: So, you went back to school?

Rosencrans: Yeah, I finished my degree at the age of 50, took my life out of that two-track working regimen, and dedicated the rest of my [working] life to service for the greater good. I’ve worked with a number of organizations. I had a consulting firm for a while, but really my heart has always been in the outdoors and in the environment. Diana and I’d worked on a project or two in the past, and when I found out that this opening existed, I jumped at the chance to work with her and the field that we’re in. It’s a perfect fit for me.

Slomovits: What are Legacy’s future goals?

Kern: In the beginning, when this was a newer concept, it really was conserving land that everyone wanted to not see developed. And I want to be clear that here at Legacy we’re not saying, “conserve everything!” You don’t want to do that, actually. It’s the high-quality land that adds to water quality, carbon sequestration, and natural habitat use [that we want to conserve]. Back in the beginning years, it was “place as many easements as we can” to start conserving land, so everything is not developed. Where it’s been more recently is looking strategically at what kind of criteria, we should be looking at in order to work with the landowner to place a conservation easement. We’re not going to place easements on tiny parcels, there’s not much value to that, but larger swaths of land, farmlands that we want to preserve, wetlands, there’s things called fens—which are natural areas where water filters—and space for habitat, those are the types of things we look at now, that’s where people are focused. That’s the future, and then for Michigan it’s all about water quality.

Sandor: Has that changed since Flint?

Kern: It’s changed since PFAS.

Sandor: Of course, PFAS!

Kern: Yes, and Flint, and all these spills, and Line 5, and… There’s all kinds of things happening in this state. Twenty percent of the world’s fresh water is in Michigan! Those four rivers that cut through this area, all of those at some point, through the tributaries and the ground water, all run to one of the Great Lakes. So it’s really looking at what we can do to help protect the water quality. That is a big focus right now.

And another focus is farmland. We’ve lost a lot of acres of farmland in Washtenaw and Jackson counties over the years. There are really big concerns about that [the loss of farmland]. Farmland is another focus area and helping to educate farmers about conservation practices so that they can be partners at the table in protecting water quality. There are a lot of great groups that have formed, farmer-led conservation groups. That’s really where the direction of land conservation is going, I think.

Rosencrans: Water needs to percolate through the land before going into the aquifers and the tributaries; that’s a critical part of keeping the water supply clean. [Land conservation] efforts really contribute a great deal in that direction. Another environmental benefit is being able to have a quick trip from the farm to the grocery store instead of having it shipped across the country. The carbon footprint, the environmental impact of having local farms operating, is considerable, and, frankly, I think the food is better, but that’s just my opinion. (Laughter) There are a lot of environmental benefits to preserving these lands.

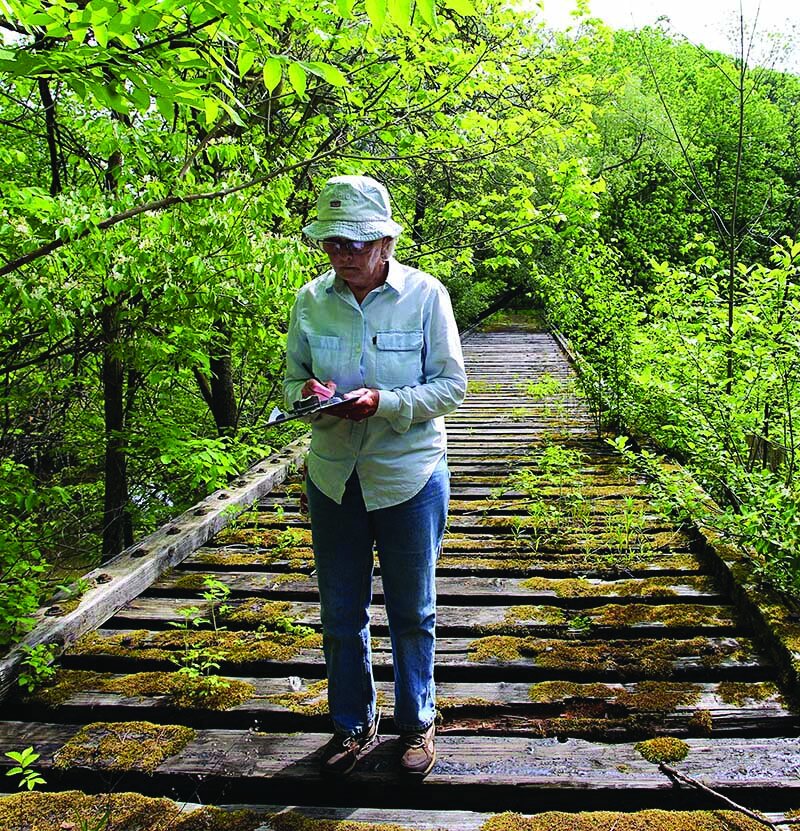

I met two other key Legacy staff members. Dana Wright serves as Legacy’s Land Stewardship Director and is primarily responsible for monitoring all of Legacy’s easements, while Allene Smith, who is Legacy’s Land Stewardship Coordinator, oversees Legacy’s seven nature reserves. I tagged along with each of them to get a sense of what their jobs entail.

Dana Wright, Director of Land Stewardship

Wright, 45, has a bachelor’s degree in Environmental Biology from Michigan State University and has worked with The Nature Conservancy, the Leslie Science and Nature Center, and with Natural Area Preservation of the City of Ann Arbor. She’s been working at Legacy since 2009, and in her first year there she launched the volunteer program to help with Legacy’s monitoring responsibilities. Annual monitoring of every one of the easements that a land trust like Legacy holds is an accreditation requirement of the Land Trust Alliance, the national association for all land trusts in the U.S. What that means in practical terms is that once every year Wright, and her crew of volunteers, visits every one of the 82 easements that Legacy currently holds. In addition, Legacy works as a contractor doing monitoring for several other organizations, including Washtenaw County Parks, who also hold conservation easements. Legacy conducted these site visits on an additional 26 properties in 2019. The combined acreage of these 108 properties adds up to almost 6,000 acres, some farmland, much of it forested, and a good smattering of wetlands.

In mid-December on a mostly sunny day, I went with Wright on a site visit to Dale and Julia Frey’s dairy farm on the west side of Ann Arbor. When we arrived at the farmhouse, Wright introduced herself to Julia Frey, who pointed us toward the barn where her husband was working with a couple of other men. We walked over, Wright introduced herself again, explained what she had come to do, and we chatted for a few minutes. Dale Frey was clearly familiar with the purpose of the visit, and Wright asked only one question pertaining to the easement, “Anything new planned for next year?” Frey said he was not planning to make any changes and, after chatting with him for another few minutes, Wright headed toward the wooded part of his property.

Wright carried a small electronic tablet that she consulted regularly. I asked her about it.

Wright: We use a GIS (Geographic Information System) mapping system. A geographic information system is software for gathering, matching, and analyzing geographic data. I’m using an app that was made by the same person who made the database. This program has our map of the property on it and all the photo points that we took during the baseline documentation. I can see where all the photo points are, and if I want to recreate them, I can go to that point. Then when I take a picture it records the direction I’m facing, creates the GPS point, and stores the picture and the point and automatically syncs with our database. If I want to reference that picture in the future, I would open the database, choose this property, and go to that point—all the pictures are there, and it says what direction they were taken in. It also records where we walked, and that’s one of the Land Trust Alliance standards; for each monitoring visit you have to record where you walked. You don’t need to take pictures every time, but you do need to have it recorded, and this software does it automatically.

Slomovits: Very high tech! What was it like before the digital age?

Wright: The first year I started with Legacy we had a bunch of maps of the properties. The maps were really old, and the focal points were created by putting stickers on the map, little pieces of paper (she giggles delightedly) and then they were copied a bunch of times, they were black and white—they were terrible. So, I created a new set of maps, in color, for all of the properties.

Slomovits: When did you go digital?

Wright: That first year the best I could do was make new maps. The second or third year I received a grant and secured GPS units for all the volunteers. We learned how to use GPS and began using the GPS to track where we were on the property and to mark where we took photo points. The most important thing is to be able to see where you are on the property [in order] to know whether you’re on the [property] line or not, if there’s a new structure, or where the corner of the lot is, if there’s something that’s going on near that line. Also, just knowing where you were, that helped a lot. We used the GPS units for three or four years. I had uploaded maps onto the GPS units, one for each property, and the volunteers would use them and bring them back to the office, and I would export the information, and they would send me pictures, and they would fill out a report, so three different things had to be done for each property we were visiting.

Slomovits: And now all that is done automatically.

Wright: Right. Now all of that is basically done with the tablet, but there’s still some things for which they [the volunteers] have to load directly into the database. They enter in things like when I was talking to Dale, I asked him if he had any plans for the next year. That’s a question that we ask just to remind them that if they have any special plans, oftentimes it’s something that we need to give permission for beforehand.

Sandor: If, for example, they decide to put up a new structure?

Wright: Yes. The farmers are usually very familiar with what’s in their easement, so they wouldn’t do something that’s not allowed, but they do have to ask for permission. They have to send us the plans, and then we come out and look at the area, whatever is in the plans, and say, “Yeah, looks great,” and then they can go ahead and do it.

As we were walking in the woods, I saw a deer blind in one of the trees and asked Wright about it. I also asked whether farmers are allowed to cut down trees for firewood.

Wright: Most farms have a woodlot and farmers are allowed to harvest deadwood for firewood as well. As far as hunting, we only have two or three easements that don’t allow hunting.

Sandor: How does enforcement work if you do spot a deer blind in one of your preserves?

Wright: What we did this year was, we posted on the gridline that this was private property, hunting is not allowed, please take your blind down or we’ll remove it, and gave them a date on which it would be removed. And we ended up taking two down.

Sandor: When you say we, does that mean Legacy staff?

Wright: Yeah. Allene (Smith) and I went out together and did that.

Slomovits: Do you monitor the properties all year or just during warmer weather?

Wright: Because I have volunteers, I hold a training every year, and so we have a definite monitoring season. I usually do my training in March, and we end all our monitoring in December because it has to be done within a calendar year. Some of the more experienced monitors will do a property before the training. Properties get monitored the same month they were monitored the year before. We have 30 some volunteers for the monitoring. They work in teams and monitor between two and ten properties each team. They do the site visits, collect the data, use a tablet like we did, take pictures, and show where they walked on the property.

We have one volunteer who has been with us every year since that first year I started the volunteer monitoring program, and there are a lot of people who have been with us for a long time. Landowners get attached to the person who’s come before. It’s good for them to have a relationship. You heard Dale say, “Oh, no Robin this year?” (Dale Frey had asked about the person who’d done the monitoring on his property the past few years.) That consistency is great for the program.

Allene Smith, Land Stewardship Coordinator

Allene Smith, 31, began working at Legacy four years ago. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in Plant Biology from Western Michigan University, and before coming to Legacy, worked with The Nature Conservancy, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the Forest Service, and the Land Conservancy of West Michigan. One of her primary responsibilities at Legacy is overseeing, maintaining, restoring, and managing Legacy’s public nature preserves, so that the properties maintain their conservation value. (Legacy does not do land management, removing invasive species for example, on the properties on which they hold conservation easements, but does do that on the preserves.) She decides what kinds of restoration projects will be done, organizes and directs volunteers in doing the work, leads nature walks, and also works on Legacy’s Land Acquisition efforts.

In early January, on a windy, overcast day, I met Allene Smith at the Lloyd and Mabel Johnson Preserve, off Platt Road, next to Lillie Park South. We started from the small parking lot, next to some Project Grow garden plots, and moved onto a mowed trail that weaved through waist high prairie plants on our way to the wooded section of the preserve. Smith carried a small electric chainsaw, and I asked her what she was planning to do on this visit.

Smith: Today is a general visit, I’m going to walk the trails, and if there are any trees over the trail, I’ll get those out of the way with the chain saw. We have these public preserve properties for a number of reasons. One is the ecologies they support, for ecosystems to be maintained, its habitat. But then, very much in tandem with that is the fact that these are also places we want to make available for people to visit, to make connections with the natural world, and feel safe and welcome. So a big part of that is trail maintenance. That’s at the top of the list.

Slomovits: Do people cross country ski here?

Smith: I don’t think people do at this preserve, though they are welcome to. I know we get a lot of skiers at our Sharon Hills Preserve in Manchester because it’s very hilly. Each preserve property is pretty distinct. The Johnson Preserve, I wouldn’t call it an urban preserve, but it’s closer to people than many of our others, so therefore we get more volunteer interest here. Also, the Johnson Preserve was the only property on which there was agricultural land, so for much of the time that Legacy has owned this property, we leased the ag land to a farmer, but then in the spring of 2016, we started the prairie restoration for that part of the land. The first choice was to keep it in agriculture and simply change the type of agriculture, but when there wasn’t anyone interested in farming the land, that’s when we decided to change it over to a more natural ecosystem. We worked with the Natural Resources Conservation Service; they have some cost share programs that help landowners with farmland that they don’t want to farm anymore, to convert it to prairie habitat. We got some help getting the seeds, planting the seeds in the ground, and now we work with them in an ongoing way to manage it.

The Johnson Preserve woodland trails get a considerable amount of activity—the prairie trails not as much. When the prairie was a farm field, we didn’t direct people there actively, but now that we have transitioned that part of the preserve, we’ve expanded the trails, and we’re trying to call people out there more. Johnson gets a lot of walkers [because] it’s near where people live.

As we walked through the woods, we came across several dead ash trees that had fallen across the trail. Smith cut them into manageable pieces with her chainsaw, and we moved them off the trail. We found an uprooted tree, arching across the trail, hung up in the branches of nearby trees. It was too big for her saw, and she made a note to come back and deal with it another day. We came to a stretch of boardwalk and, though the ground was dry, I asked if it got wet in the warmer months.

Visit Krasnick Regenerative Medicine online at krasnickregen.com.

Smith: Yes, right here is a buttonbush swamp. The trails that encircle it, which are kind of the main feature of the preserve, they get really swampy. We allow bikes at this preserve only, not at our others, and so that has some impact on the trails, especially when they’re wet, so we’ve had some boardwalks here before, but we needed more. This stretch of boardwalk is brand spankin’ new, put in just this past summer, by an Eagle Scout who brought volunteers with him to help with the project. He took the lead on it, making it happen. There’s another wetland loop here, an offshoot loop that was put in in 2017 by a group of teens from the Neutral Zone. They put in about a half mile of trail winding through the woods. One of the parents of one of the teens who put in this trail was legally blind. As these teens and their parents took the first hike down the whole completed trail, this young woman and her sister, one on either elbow, were guiding their parent. It was a really beautiful thing to see, not only the familial love, but also that this person, who maybe didn’t have opportunities to be in a woodland very frequently, was able to do that.

A bit further along the trail we found another fallen dead ash tree across the boardwalk. Smith sawed it in two, and we moved it off the trail. She said that sometimes she’s had to replace boards damaged by fallen trees.

Slomovits: How do you track what needs to be done at each preserve?

Smith: We’re available enough that we can be found through our website by the public if there are issues. People call or email about problems. We don’t have a dedicated person at Johnson, but at several of the other preserves, we have what we call preserve-adopters—people who visit frequently enough, once a month or so, to be able to catch things like trees over the trails. I’m in communication with those folks relatively frequently, and if there are issues that are beyond what they feel comfortable handling, I take over. There’s a stalwart volunteer who mows the trails at our Sharon Hills Preserve, and we also have a caretaker at our Reichert Nature Preserve near Pinckney. She lives there with her family, and they’re very present. In the summertime, when we’re doing a lot of stewardship work, land management work, I or one of our stewardship crew members visit almost weekly. Especially on days when I’m feeling stir crazy and want to get the heck out of the office, it’s great to [be able to say,] “You know I haven’t been to Johnson in a little bit.” I’ll go walk around, make sure everything is looking like it should.

Susan Lackey, Executive Director, 2005-2016

I also corresponded with Susan Lackey, who served as Legacy’s Executive Director until her retirement in 2016. She began in that role in 2005 for Washtenaw Land Trust (WLT), the organization that eventually evolved into Legacy. Prior to coming to WLT, she was president of the Washtenaw Development Council.

Slomovits: How did you become interested in land conservation?

Susan Lackey: I became interested in sustainable development and the need to maintain quality of place for communities that were going to prosper in the 21st century, which lead me to conservation. Or, maybe, back to conservation. I began my career doing rural regional planning in Southwest Michigan, where I grew up, shifted to urban economic development in Benton Harbor, and then came to Washtenaw Development in 1994. In all these jobs, the nature of the place was critical to success, since without a strong sense of place, it’s difficult to attract or keep people.

Slomovits: What in your childhood, or family history, may have led you to do this work?

Susan Lackey: I grew up on a small farm. Both my parents were very observant of the wildlife they shared the farm with, but my father particularly so. He also had infinite patience with a small child. He taught me to sit quietly and watch a rabbit playing in the fence row, to recognize “good” plants in the woods and pastures, and also made it infinitely exciting, bundling me onto his shoulders to go snowshoeing during January full moons. I’ve stolen one of my favorite lines from him: if you take care of the land, the land will take care of you. So my childhood, and my “ how soon can I get outside” view of my leisure time, and land conservation seemed to bring all my personal and professional experiences together.

I asked Lackey for a history of her tenure at Legacy and its predecessor, WLT.

Lackey: Legacy (via its predecessors) is the oldest local land conservancy in Michigan. But in 2005, we were experiencing a prolonged organizational adolescence and struggling to understand what we wanted to be as an organization. This made fundraising a constant challenge, and, frankly, it seemed like a community with as much history of environmental and conservation activism as we have deserved a more robust private nonprofit land trust effort. Our first task as an organization was to define what success would look like. First, we realized that our state parks (Waterloo, Pinckney, and Sharonville) and our rivers (Huron, Raisin, and Grand) provided something of a natural boundary for our work, but that it extended beyond Washtenaw County into Jackson, where no active local conservancy was engaged. This resulted in the name change and, ultimately, the definition of the “Emerald Arc” the rivers, public lands, privately held natural areas, and farmland nestled into the arc formed by those places—served as a driving force for our work.

I have gotten a lot of credit for this over the years, but in truth, if credit is going where it’s due, it was the Board that started looking at maps and realized what had been in front of us all the time. There were four other things that defined those early years as well. This was in the midst of the national real estate boom, and, in some parts of the country, developers had used conservation easements to take inflated tax deductions for land they would never have been able to develop anyway. Congress threatened the entire tax structure of land trusts as a result, and our national association, Land Trust Alliance, responded with a voluntary accreditation program. We knew—or thought we knew—we did things right, but it was more out of good character than formal systems that prevented bad action. So we volunteered to be one of the pilot organizations to go through accreditation. This was expensive, time consuming, and really scary. In fact, at one point I got cold feet and began to question whether we were doing the right thing, only to discover that my staff, in anticipation of that, had sent in our preliminary application before I could change my mind! It’s good to work with good people. The result of all this was that we were one of the first conservancies in the nation to be accredited and have reaccredited twice since then. The process also helped us form the detailed plans we needed to turn the idea of the Emerald Arc into a workable idea.

Visit Fiery Maple online for more information.

Conservancies do their work “forever,” and that puts interesting constraints on us. Specifically, we have to have cash on hand to face any legal challenge that might arise to our projects, which place permanent restrictions on privately owned land. This can be as simple as having to confirm boundaries for a neighbor or as complex as someone deciding to build a roller rink in your protected wetland. We’re supposed to have some type of endowment or legal defense fund for that work, and ours was woefully inadequate and threatened our accreditation as well as our ability to look people in the face and say, “Yup—forever.”

In early 2008, the Herrick Foundation offered us a challenge grant to establish what we called our Forever Fund for that purpose. Unfortunately, early 2008 led to late 2008, and the financial crisis and we, along with other nonprofits, feared for our ability to keep our doors open, much less raise money that we hoped we’d never need to use. Fortunately, we had good board members—again—who helped us identify some assets (a cell tower on a nature preserve donated the prior year to Legacy) that could be converted to cash, which solved our operating needs and let us focus on meeting the terms of the grant. Board members and others stepped up to introduce new people to Legacy, and we met the McKinley Foundation challenge. We all took so much pride in being able to explain to landowners that this was how we could look them in the eye and say “forever” and mean it.

The final thing that defined those early years was the decision to change the name of the organization. We believed (and it’s been borne out over time) that our service area would gradually expand. And we also knew that it was really difficult to get folks to think of the Washtenaw Land Trust as “their” conservancy if they lived in Jackson, Livingston, or Lenawee Counties. So we went through a process, about the same time as accreditation and filling the Forever Fund, to change the name into something that would be able to stand the test of time. That included the now famous “nest” that is Legacy’s logo. It’s a bluebird’s nest, which describes one of America’s great citizen conservation successes. From the moment we unveiled it to a fundraising dinner, people have loved that logo. It really defines what we do.

Charity Steere, Board Member

I also corresponded with Charity Steere, longtime Legacy Board member and volunteer. Steere, 71, began serving on the Board in 2003, when Legacy was still named the Washtenaw Land Trust. At the time she was on the board of directors of Waterloo Hunt Club (WHC) and was chairman of their hunter/jumper horse shows.

Slomovits: Tell me about your work at the Waterloo Hunt Club.

Charity Steere: WHC had formed a small land conservancy with the goal of protecting some of the land they hunt over in and around the Waterloo Recreation Area (WRA), and I was a member of that conservancy board as well. When it became obvious that the Waterloo Conservancy was too small to accomplish our goals, the president of that board began searching for an organization with which to merge. WLT had recently joined forces with the Potawatomi Land Trust, and one of the expectations of that merger was that WLT would work to protect land in and around the WRA. The merger of WLT and the Waterloo Land Conservancy followed as a logical result. The Waterloo Land Conservancy was offered a seat on the WLT board at the time of the merger, and I volunteered to fill that seat, largely because I live within the WRA.

Sandor: What have been the primary issues, challenges, successes, and goals of Legacy during your tenure?

Steere: Legacy’s challenges are very similar to those of any other small non-profit organization. The mission is to create more work than staff can possibly accomplish. The task is finding and retaining top-notch, dedicated staff, funding the day-to-day operations, and meeting the challenges of a growing organization, along with the community’s expanding need for the service it provides. Community education and outreach about the mission is also necessary and demanding. Where the challenges Legacy faces differ from other non-profits is in the nature of the work. Every property Legacy protects adds to the workload because each additional property needs to be monitored annually—more property equals more work. Nothing especially unusual there, except that Legacy, like all other land conservancies and trusts, promises to do this in perpetuity. So every document must be written and preserved with that in mind, and, most significantly, the future monitoring and defense of those conservation agreements must have endowed funds to ensure that that commitment to perpetuity is met.

Sandor: What in your childhood and upbringing contributed to your association with Legacy?

Steere: My first brush with the consequences of development occurred when I was in first grade. Every day I walked to and from the one-room country school just down the road. When Interstate 127 was built, the construction went across our road right between our house and my school. This crushed my dream of riding a two-wheeled bicycle to school for second-grade instead of walking. As it turned out, it also closed my school. The other consequence was that it made me forever skeptical of development.

I’ve always lived in the country because our family has always had horses and kept them at home. Riding space has come at an increasing premium, more and more difficult to find and retain, so the opportunity to protect additional riding country in and around the Waterloo Recreation Area and to buffer that natural area from the consequences of development (like paved roads) was important to me.

Development is necessary, and in many cases desirable, but, in my opinion, it must be appropriate to, and in consideration of, the nature of the land and its “highest and best” use.

Sandor: I’ve been told that besides your work on Legacy’s Board, you also volunteer.

Steere: When one of Legacy’s early calls for new volunteer photo-monitors went out, I rather petulantly decided that I was doing enough and didn’t want to dedicate any additional time, so I refused to take the training or join a monitoring team. Besides, it would have involved learning some scary new computer skills and learning how to use a GPS unit. So when my husband and a good friend did volunteer, at first, I refused to accompany them on their monitoring visits. But when they came back raving about how much fun it was, and what cool things they were seeing, I agreed to go along on their next visit. I’ve joined them on every subsequent trip and love it! Seeing the wonderful properties Legacy has protected and all the plants, critters, and natural features on this land is amazing and inspiring and has really cemented my commitment to Legacy’s work. But I’ve still avoided improvements to my computer skills or learning to use the GPS unit. Best of both worlds!

Final Words

All of the people I talked with at Legacy had some similar qualities in common: a deep love for the natural world, a shared sense of responsibility, a dedication to saving and passing along beautiful natural areas, and the desire to protect the environment. All seemed to feel a deep sense of satisfaction from working and volunteering for the Legacy Land Conservancy, and they all communicated lyrically, almost poetically, about their service to the land.

Diana Kern: We’re coming up on our 50-year anniversary, and we’ve been involved in protecting over 9,200 acres of land so far. We have a bigger goal of 25,000 acres. Like any good non-profit, you do strategic planning, set goals and visions. This year we will be talking to partners, the community, and our donors and asking, “What’s the next space that Legacy should be in? Where should we be going for the future?”

I’m really excited to do that. How are we engaged with the community on a bigger level? How are we helping with climate change, carbon sequestration, water quality? What role can Legacy play in those areas, while at the same time working with all of our landowners? We’re not just a land deal non-profit. We’d like to be at the table, helping with education and outreach. I think that’s something that the community needs to know, that we want to be part of that bigger discussion and solution.

Scott Rosencrans: This is what we do. We’re a small and humble organization, yet we keep plugging away with lofty goals. This is our thing—conserve the land, help the environment, help folks stay on the land, if that’s what they want to do.

Susan Lackey: All that Legacy has done wouldn’t have happened without good staff and good board members and volunteers. But the most important people in the process are the landowners. I’ve sat at kitchen tables with farmers who tell stories of their grandfathers and great-grandfathers homesteading the land, including one who led me out to show off the beech tree with his great grandfather’s initials carved in it, along with the date, 1832. I’ve walked a piece of land with a woman who had purchased it because she loved the sandhill cranes who were, at that moment, grazing peacefully in the field below us. I’ve visited a pine forest with a family who had wonderful memories of working with their father and uncle to plant thousands of seedlings in a played-out field and seeing the fairy rings that made the entire place seem magical. I’ve watched a kindergartener discover how fascinating minnows can be at the edge of a pond. I heard a woman tell me how she used the inheritance from the sale of her parents’ farm to buy one of her own, and how she had to fight with the seller because he kept insisting that she needed a man to advise her. And then how for the next 20 years, she worked to create better habitat for the many butterflies she discovered there. I’ve walked through a hunting property with the owner, who sheepishly admitted that he was doing less and less hunting and more and more sitting and watching as he increasingly got to “know” the game on his property.

Dana Wright: I grew up in northern Michigan on the shores of an exquisitely beautiful lake surrounded by maple forests and cherry and apple orchards. In the summertime I had tropical-blue, clear waters to swim in, sprawling and wise trees to build forts in, wild strawberries, mushrooms, leeks, and orchard fruits to enjoy. In the wintertime I had snow-covered sand hills for sledding and an icy lake for skating. Being connected to the natural world on a daily basis is my heritage. A career to protect that world, and foster in other people the type of connection with nature that I was allowed to have as a child, is a path I've always enjoyed.

Allene Smith: We’re not a super well-known organization, and conservation easements are not very well known, but it’s really easy in this world to get discouraged. I graduated [from college] during the recession. I didn’t have a lot of opportunity right out of the gate professionally, so to have found this part of the conservation world… A conservation easement is something that’s real, it feels real and tangible. There’s an actual measurable impact. There are calculations that we do as part of our grant funding, we actually assign a number to different water quality metrics, what a conservation easement actually equates to in terms of water quality protection and things like that. It feels so real, it’s refreshing. And at a time when there are so many things that are intangible, immaterial, and theoretical… Definitely one of the reasons why I keep on keeping on.

Charity Steere: When asked to describe myself I say “horsewoman, housewife, and gardener,” even though I no longer have horses. I worked as a public librarian for several years and ran a great many horse shows and other equestrian events, but the only really significant work I’ve done, work that will have any lasting value, is the work I’ve done with Legacy Land Conservancy. This is work that matters, and I’m really proud to have been a part of it.

As a gardener, and a general nature romantic, my heart begins to feel torn around mid-February. On one half, I want to honor the last of winter’s deep rest and on the other half, there is the burgeoning energy of spring’s return. One of my favorite activities at this time is to thumb through my seed stores, as well as the new year’s seed catalogs, and begin to plan my garden in earnest.