By Joshua B. Kay

"I never imagined a time when craft beer would become so mainstream,” said Rene Greff, co-owner of Arbor Brewing Company brewpub in Ann Arbor and ABC Microbrewery in Ypsilanti. In 1995, when Rene and her husband, Matt Greff, opened the brewpub on Washington Street, craft beer was anything but mainstream. A few brands were paving the way, including Samuel Adams in Boston, Sierra Nevada and Anchor Brewing in California, and Bell’s Brewery in Michigan, but American beer sales and consciousness were dominated by light, insipid lagers produced by mega-breweries like Anheuser Busch, Coors, and Miller. The American palate was trained to expect beers with thin body and little flavor. Jumping into the nascent craft brewing industry was an act of courage and faith that the nation’s tastebuds would come around.

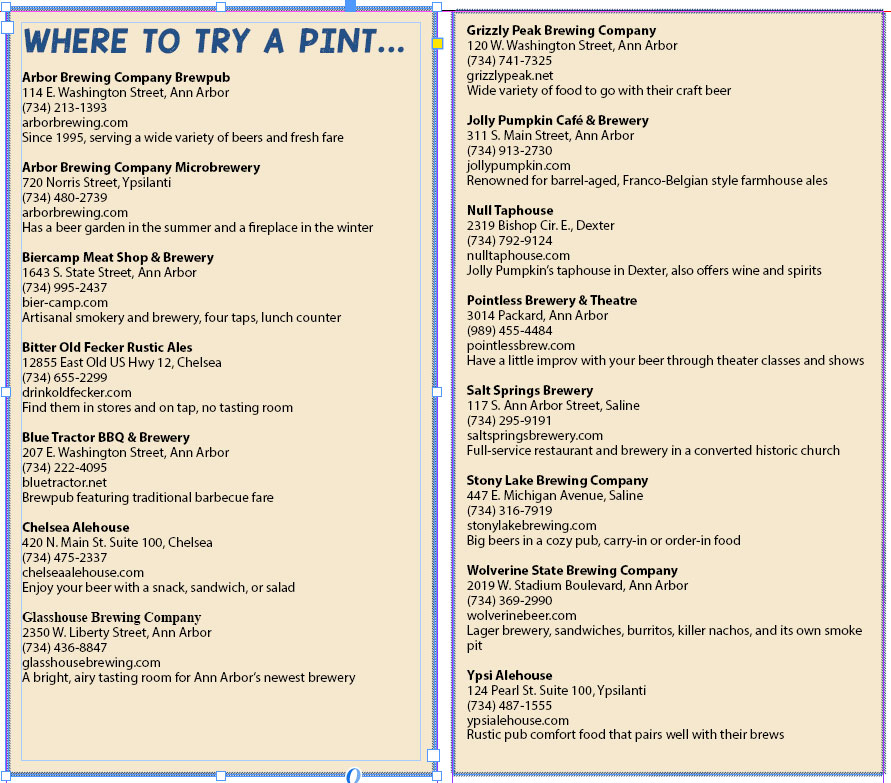

“When we opened, we were the seventh brewery in Michigan,” Rene told me. She estimated that there are now over 250, but she confessed that she can’t keep track of them all. The Michigan Brewers Guild lists 207 member breweries on its website. As someone who has followed the industry for over 20 years, I remember noticing when we hit 50, then 70, and then 100, and then one day realizing that breweries were opening too quickly for me to keep up. As I write, there are at least eight in Ann Arbor, with another under construction on the west side. Ypsilanti has two, as do Saline and Chelsea, and Dexter has one. The American beer industry has never had so many breweries producing such a wide variety of brews, and Michigan is a leading craft beer state. The Michigan Brewers Guild estimates that Michiganders are never more than an hour from a brewery and that the total economic impact of the industry is well over half a billion dollars.

“The Michigan Brewers Guild estimates that Michiganders are never more than an hour from a brewery and that the total economic impact of the industry is well over half a billion dollars.”

Yet despite their statewide and even national impact, brewpubs and brewery tasting rooms and restaurants are decidedly local places, places where communities gather to celebrate, relax, debate, and play. Rene Greff said that she and Matt just wanted to “open a little place where people could get a beer and some food and we could talk with them across the bar.” As large and varied a business as Arbor Brewing has become (in 2013, ABC opened a brewpub in Bangalore, India), the Ann Arbor brewpub and Ypsilanti microbrewery are still places where casual chats across the bar happen all the time.

The idea of a “little place” for people to gather, a community place, is the thread that connects the breweries across the Ann Arbor area. Ann Arbor’s newest brewery, Glasshouse Brewing, opened this summer. Head of Operations Cole Bednarski noted that people work hard day in and day out, and a brewery is a “conversation space” where they have an opportunity to just enjoy themselves.

Similarly, Jerry and Heidi Tubbs opened Stony Lake Brewing in Saline in November, 2015, to give the town the sort of social gathering spot it had previously lacked. They’ve decided not to have TVs despite some pressure to do so. Jerry said, “For every person who bugged us to add television, there were two that whispered in our ears ‘don’t ever get televisions.’” Without televisions blaring, there’s room for conversation, and Jerry pointed out that on Friday and Saturday nights, Stony Lake is packed with people talking and playing board games. Jerry credits Arbor Brewing’s microbrewery in Ypsilanti for inspiration, noting that he and his wife could sit there either inside or in the beer garden and just enjoy conversation and meet new people. “It brings people together,” he said.

Also in Saline, the owners of Salt Springs Brewery carefully converted a historic former church into a brewery-restaurant. Original stained glass filters sunlight into the large dining room, where the ceiling features a huge painting of a deific hand pointing to a cluster of hops. Like Stony Lake, Salt Springs has sought to give Saline something the town didn’t have. “Our instincts told us that in this building, in this setting, in this town, with the right menu and making really good beer, people would embrace it and it would be something for Saline to be proud of,” said co-owner Ron Schofield. He added that lots of nearby towns have breweries, and before Salt Springs and Stony Lake opened, Saline “had a demographic that wasn’t being served.”

Opening on the southeastern edge of brewery-rich Ann Arbor, Jason and Tori Tomalia looked to create and occupy a unique niche when they opened Pointless Brewery and Theatre. The couple shares a theater background, and they believed that theater and craft beer make a good combination. Pointless has an in-house improv company, the League of Pointless Improvisers, which Jason directs, and even offers Saturday morning children’s theater programs run by Tori since the tasting room isn’t open in the morning. The couple shares a passion for providing performance space for the community. Jason noted that some people come mainly for the shows, others for the craft beer, and there’s a lot of cross-pollination as craft beer aficionados fall in love with the theater offerings and theater fans discover craft beer. The combination is made manifest in an improv show called Test Batch; local improvisers get some stage time, and the audience also submits suggestions for new beer flavors and styles. Jason told me that he is especially proud to have created a community space for collaboration, laughter, and play.

Other local breweries fill niches that are more particular to beer. Wolverine State Brewing Company on Ann Arbor’s westside specializes in lager brewing as opposed to ales. Brewed at cooler temperatures and requiring a long period of cold storage, called “lagering,” lagers are known for clean, crisp finishes. Wolverine set out to show that lagers aren’t limited to the light, yellow versions from the mega-breweries, and the taproom features a wide array of beers, from stout-like dark beers to a top example of India pale lager that has spurred other breweries to create similar offerings. Wolverine also offers a food menu, including pulled pork smoked in-house.

Dexter’s Jolly Pumpkin, which has a restaurant in Ann Arbor, occupies a completely different category, specializing in the beers native to Franco-Belgian farm regions.

Barrel aged and carefully blended batch by batch, these farm ales can be sour, funky, and fruity, with complex wine- and cider-like flavor profiles. A forerunner of the barrel aging craze that has swept craft brewing, Jolly Pumpkin has achieved international renown with its beers.

Rounding out the brewpub scene in Ann Arbor are Grizzly Peak and the Blue Tractor, both on Washington Street. “The Grizz” offers a broad food menu and a wide array of well-crafted beers. The Blue Tractor features barbecue fare and a beer selection that has blossomed over the years. Finally, Biercamp on South State Street combines a market and lunch counter featuring house-smoked and cured meats with a small brewery, with beers available for on-premise consumption or to-go.

As more and more breweries have opened, competition has increased. Rene Greff described a huge amount of industry growth in the 1990s, followed by a contraction in the early 2000s. At the time, she thought she had seen the “industry’s growth spurt, and from there on out, it was just going to be sort of steady, maybe a little bit of growth.” But the industry was by no means done. “I don’t think anybody saw the second wave coming. In the late 2000s, we went into another huge expansion that has been much bigger, much more explosive, than the first expansion.” Nevertheless, she said, “We may be seeing [a contraction] happening again.”

Asked why, she replied, “This movement, more than many other market growth movements, is about authenticity, and customers can spot it in a second. So if you open a place and you don’t have a passion for beer and you just see it as a profit center, people are going to sniff you out as a fraud.” She thinks that’s happening now as venture capitalists buy up breweries merely because they see them as opportunities for big profits.

In addition, with the proliferation of craft breweries and the fact that craft beer is much more mainstream than it once was, consumers have become more discerning. It’s no longer good enough to be the local place serving mediocre beer. Now breweries need to make consistently good beer to survive. Those that don’t, or that market themselves as “craft” yet make beer with additives more common to the mega-breweries, risk not only closing but also damaging the industry as a whole. As Rene put it, “We’ve worked really hard to build consumer confidence in craft beer so that a consumer can go into a store and grab a six-pack of a beer they’ve never had and have the confidence that it’s going to be good.” The danger of turning off consumers and scaring away newcomers is a significant challenge faced by the industry.

““This movement, more than many other market growth movements, is about authenticity, and customers can spot it in a second. So if you open a place and you don’t have a passion for beer and you just see it as a profit center, people are going to sniff you out as a fraud.””

I asked Rene how much room is left for further growth in craft brewing in Michigan. She said, “I think we’re going to continue to see tons of growth in local brewpubs, nanobreweries, and local microbreweries. We’re going to see contraction — and are already starting to see it — in bigger breweries, especially the breweries that need national distribution. We’re starting to see a tremendous amount of consolidation in the industry, with big breweries buying smaller breweries and trying to expand their footprint.” Overall, she predicts continued volume growth but fewer players in the larger market, but small, local breweries making great beer should continue to multiply and thrive.

After I moved to Ann Arbor in the fall of 1994 as a craft beer-loving graduate student, I was thrilled to learn that two new brewpubs were opening on Washington Street. I remember watching their construction impatiently. In July, 1995, Arbor Brewing Company opened, followed about a month later by Grizzly Peak just down the street. I never would have predicted that within the next two decades, Michigan would become a major player in craft brewing, and Ann Arbor and its surroundings would have over a dozen breweries. Each shares the desire to provide a space for the community to gather, relax, and celebrate, even as each fills a slightly different niche. As Cole Bednarski of Glasshouse Brewing told me, “Keep your eyes open, because this place is always going to be changing.” She was describing the desire to produce experimental beers at Glasshouse, but she also could have been describing our dynamic craft beer scene.