By Elizabeth J. Wilson

Have you ever attempted to create a self-portrait? I was required to do just this in a number of fine art college classes, from figure drawing to figure sculpting. I recall it being an uncomfortable experience to spend that much time looking at myself in the mirror. The point of the assignment was to learn to draw or sculpt using the available model — myself. The unexpected benefit was that, in addition to improving my skills as an artist, it led me to a new level of self-acceptance.

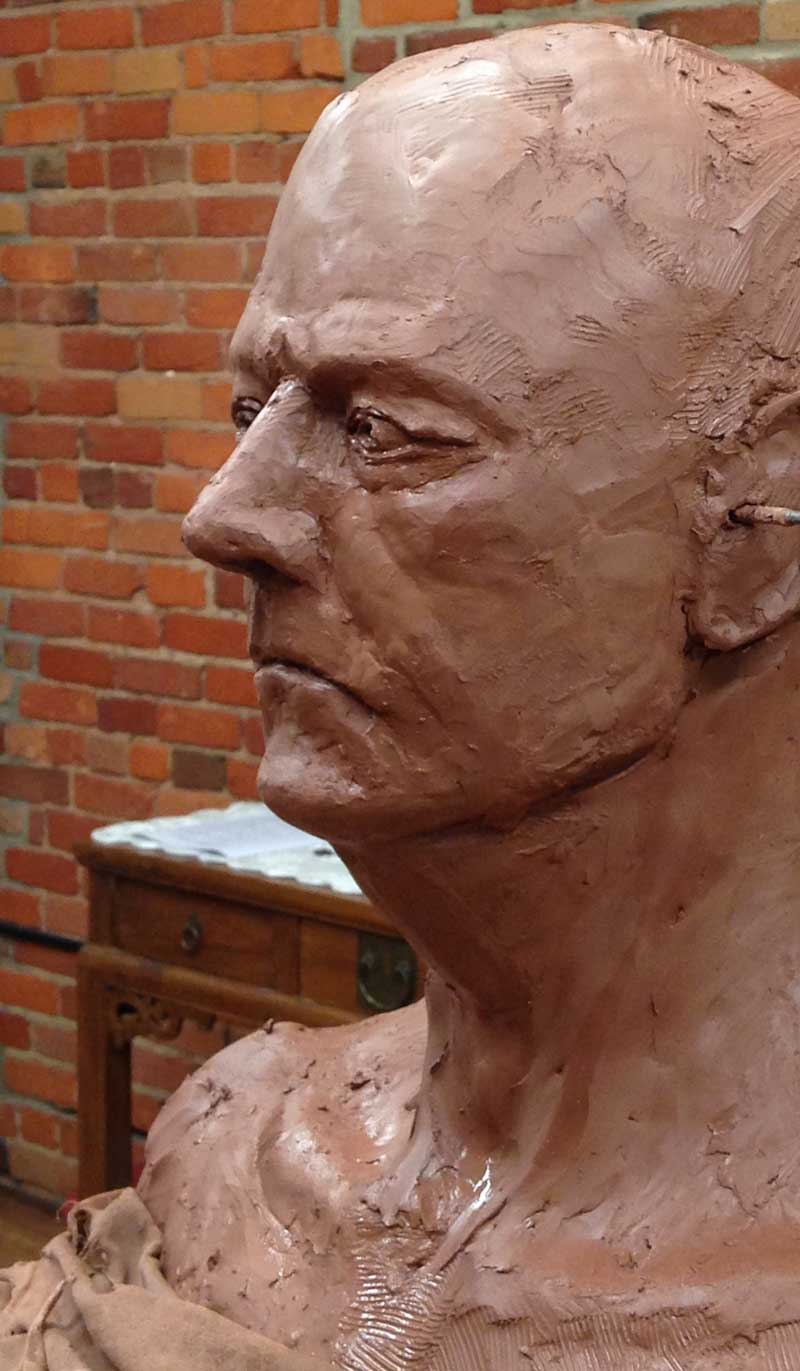

These days I find myself assigning the “unpleasant” task of a self-portrait to students (ages 17–70+). The reasoning behind the assignment is the same — simply being able to have a live model to work from when learning to draw or sculpt in clay. I watch as students struggle with the necessity of sculpting themselves. No student has expressed to me an interest in creating a self-portrait. They proceed, with coaxing, because they want to learn the technique. They are not aware of the impact it could have. However, as they work through the process, they see a transformation in how they feel about themselves. I was not intending, nor expecting, such a change in my students. The thought was to simply guide them through a technically oriented art project where they work from a live model over a period of 10 weeks.

I knew that psychologists used self-portraiture to help clients work through personal issues but did not know much more than that. The experience of seeing the change in students during the class made me want to learn more about the psychological impact of creating a self-portrait. In my research I found there is abundance of literature to support the usefulness of exploring self-perception through self-portraiture. Art therapy, including the self-portrait, is used in psychotherapy for all age ranges. Creation of a self-portrait can be used to provide insight into a child’s self-perception and family dynamics. There is research regarding the beneficial use of the self-portrait in adolescents to improve self-esteem, which in turn reduces unhealthy behaviors. There are types of therapy available to adults where self-portraiture is a component to work through concerns of self-worth and self-esteem.

“The experience of seeing the change in students during the class made me want to learn more about the psychological impact of creating a self-portrait.”

Over the last two years, I have noticed this pattern of change in every portrait sculpture class. There is an unintended but positive transformation in students as they work through the process of creating their self-portraits. Many students start out critical of themselves, so it can be an emotional undertaking. I work to provide a safe and supportive environment as they are guided through recognizing the preconceived image they have of themselves. They learn to see themselves as they are instead of the visual interpretation they have had stored in their brain for so many years. The topic of “seeing” is frequently discussed in class because students generally sculpt (or draw) what they believe they see rather than what they do see. Their artistic skills improve once they are aware of this difference.

The pattern of change goes as follows. In the first week of class, students voice concern about the idea of creating a self-portrait. They have no interest in sculpting themselves. I explain it is simply an exercise to learn the sculpting process. We focus on the technical aspects of building an armature and discuss basic anatomy of the head, neck, and shoulders. In week two, each student uses calipers to take measurements of their own head, neck, shoulders so they can start to block in the larger forms, again this is acceptable and they have fun working with the clay. Into the third week they take more detailed measurements and then we get out the mirrors and/or take photographs as references. Looks of discontent are seen around the room.

“Students learn to see themselves as they are instead of the visual interpretation they have had stored in their brain for so many years. ”

During the fourth week, they ask, “Can we sculpt ourselves as younger, thinner, with smoother skin, a smaller nose, a different hair line, etc.”? My response to this is: “It is fine as long as it is done with intention because the purpose of this class is to learn to see more accurately and create with intention.” We are half way through the 10-week class and they doubt the calipers’ ability to measure accurately. They say, “My face is not that thin” or “My nose is not that short.” The image in their head does not fit with the measurements they take. Wondering what is wrong, they measure again to find the calipers are right and they realize they do not look like image they have in their head. Around week 6 or 7 students begin to say, “I see my mother (sister, father, brother, uncle, son) in my sculpture.” This demonstrates that they are capturing their own essence but only recognizing it in their relative.

“They see the beauty in their own face in the curves, forms, and relationships that make them unique. ”

Nearing the end of the class I hear students say with some surprise, “My nose is not so large” or “I look younger than I thought” or “my eyes have a nice angle to them and they are different from what I imagined.” They see the beauty in their own face in the curves, forms, and relationships that make them unique. As the class comes to an end, they are enjoying the work on their self-portrait. Many have shared with the class that the experience changed the way they feel about themselves in a positive way.

Self-portraiture, as a drawing or sculpture, is something anyone can explore on their own or with a class. I don’t believe many adults have considered creating one. However, I would like to recommend it because the act of creating a self-portrait can be very enlightening.

Elizabeth J. Wilson is the owner of VEO Art Studio in Chelsea, Michigan, where she teaches figure sculpture and drawing classes. She has an M.S. in Health Education, a B.F.A. in Figure Sculpture, and an M.F.A. in Medical & Biological Illustration.

One cannot compare or try to match some other creative work with one’s own work; one needs to allow creative energy to blossom from within. I did not know how to do this. I had not been to art school nor studied art history. But I loved art: in museums, in nature’s unique and unsurpassable expression . . . in all manifestations.