Nawal Motawi

By Maureen McMahon, Photos by Tobi Hollander

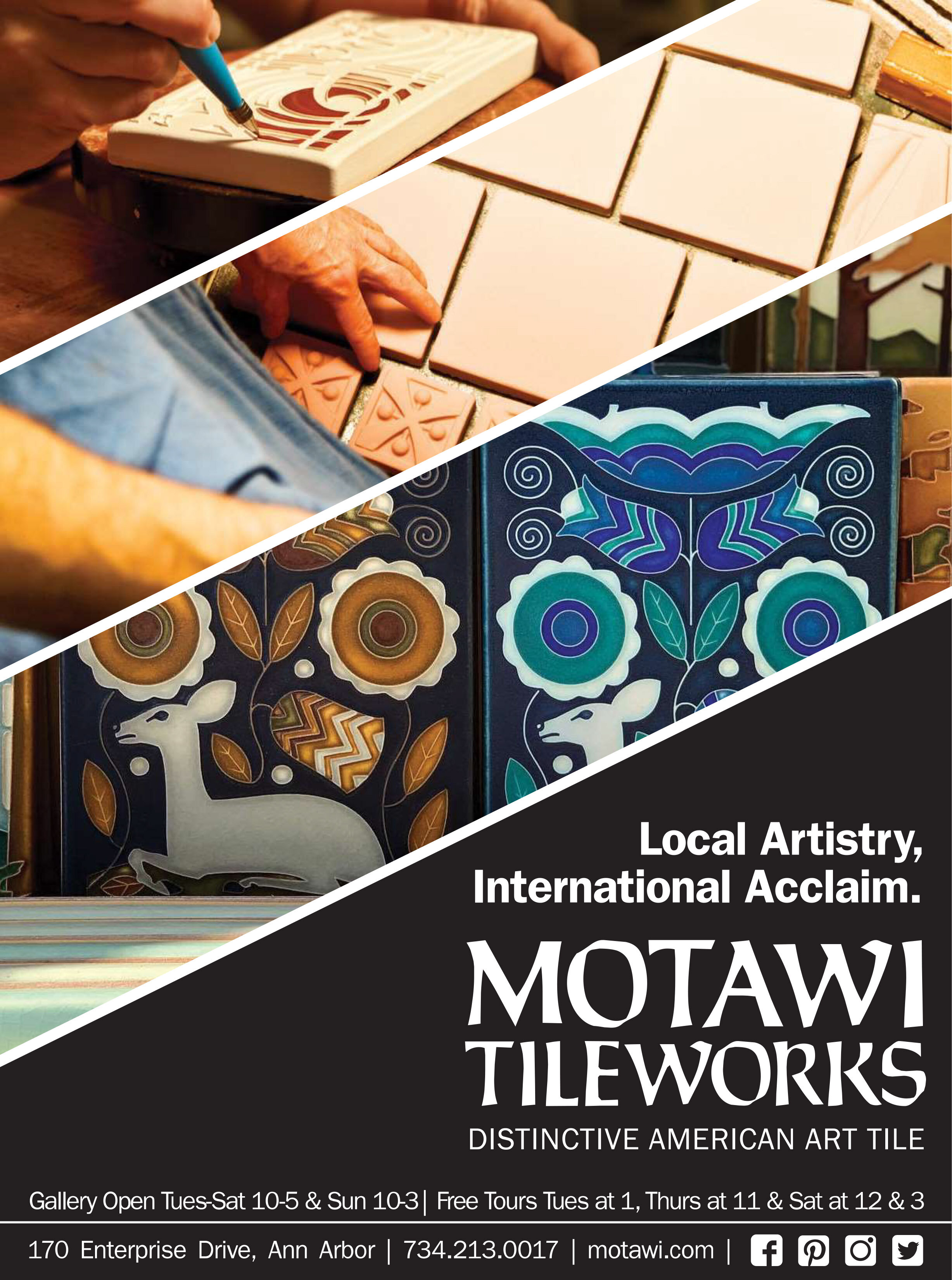

Scattered throughout Ann Arbor, and in homes across the United States, the jaw-dropping showstopper of a renovation is a longed-for big statement and focal point boasting the lush colors, careful curves, and elegance of Motawi tile. Be it a rich palette of field tiles gleaming across a foyer, colored Celadon and Caribbean Blue, and framed with nature inspired accents, or a graceful interpretation of Charley Harper’s red birds, installed within a kitchen surround, becoming the trill and warm quiet of the woods, ceramic artist Nawal Motawi’s decorative, handmade tiles elevate the statement of the space.

What began, in 1992, in a garage workshop on Packard Street has become the leading manufacturer of art tile in the United States for over a decade. With robust tile sales and an installation operation in Ann Arbor, distinct murals on view across America, and decorative accent tiles that are the favor of museum gallery buyers and their peers, Motawi Tileworks and its sister business and clay supplier, Rovin Ceramics, are among the most impressive niche businesses in Michigan.

Their catalog states, “At Motawi Tileworks, we handcraft our tiles with a design aesthetic that is both historically inspired and often borrowed from the natural world. While our earliest tile images were derived from Medieval, Art Nouveau, and Arts & Crafts motifs, our design language has expanded to incorporate the Mid-Century Modern movement and internationally inspired patterns.” Flipping through her extensive library for inspiration, an old motif or design must speak to Nawal Motawi and clearly express the perfect potential for her design translation; a conspicuous choice among hundreds. Otherwise, the designs arise from her own sensibility.

The State of Michigan recently recognized Motawi as the Women-Owned Small Business of the Year. Asked where her business is in the narrative of the state, Motawi answered, “I’d like to think we are a jewel. A little treasure that came out. As well as a Michigander that had a vision. God bless the business climate, and the freedom was enough to allow me and the company to live and grow on the merits of the products.”

Back when it started, Nawal (pronounced No-elle) Motawi was a young artist fresh out of University of Michigan Stamps School of Art + Design. She was raised the eldest daughter of an Egyptian-born food scientist and Gerber Foods researcher, Kamal El Din Hussein Motawi, and Karen Kitson, in Fremont, Michigan. For two years she apprenticed at Pewabic Pottery learning the craft and business of classic tilemaking.

In her early twenties, Motawi knew she was onto something when her first attempts at a green Medieval motifed relief tile started selling at the local farmers’ market. A self-described devoted nudger (referring to the nudge tool on her design software), Motawi is most herself spending ten hours perfecting the curves on an 8 x 8 tile design. The possibilities of the curve, and her love of history and color, have remained threads throughout her work, as well as what she called “the things people love about Motawi work.” Whenever she interprets an idea, she said, “There’s going to be a focal point, there’s going to be some drama. There’s gonna be some kind of movement to it. It’s going to have the hallmarks of the things that I bring out.”

From reinterpreting Greuby Fiaence’s Pine Trees to bringing Frank Lloyd Wright reimagined to mantles and gorgeous wooden frames, she sees the possibility of an old form and, as she put it, “Motawi-izes it.” Her designs utilize the old Spanish technique called cuenca, or the creation of basins for the application of polychrome glaze.

We apologize for mis-identifying Karen Kromrei (pictured above), general manager at Motawi, as Colleen Crawley in the print edition of issue #75.

From the innovators that inspire her to her industry peers, the artistry of her brand is seen as sophisticated. She is exclusively licensed to several Arts & Crafts archives that trust her with their portfolio. Motawi Tileworks is the sole licensed manufacturer of Frank Lloyd Wright tile designs worldwide, with their foundation trusting her to interpret its guarded archive. Similar arrangements have been made with Charley Harper and Louis Sullivan. The famed Arts & Crafts furniture designer Stickley just put Motawi bookmatched tiles of a river scene in a standard console table, drawing the eye of the modern buyer to a classic form

Read related article: Art, Health, and Wellness

As for high art public murals, Ann Arborites will have seen Motawi Tilework’s striking deep turquoise installation in the downtown Y.M.C.A. lobby surrounding the names of donors; their stunning, giant quilt murals adorning 17 elevator alcoves of the University of Michigan Medical Center; and the whimsical storybook themed Boy Reading murals in the children’s sections of the Pittsfield Branch of the Ann Arbor District Library and the Downtown Ypsilanti Library. Longtime Motawi employee Lester Bates bought the latter, weighing in at 130 lbs., as a gift for Ypsilanti with his years of accumulated staff appreciation vouchers.

Pride in Arts & Crafts revival workmanship, a thoughtful business owner and artisan at the helm, and a team of some 38 dedicated employees are responsible for one of the most respected contributions to American art tile and design active today. They come from Ann Arbor, Dexter, Ypsilanti, and Chelsea, and they do it with pride, in a 13,000 square foot factory on Enterprise Drive and a 7,000 square foot clay works on Dino Drive, on the far westside of Ann Arbor.

A Tradition of Fine, Handmade Art Tile

Michigan’s reputation for fine, handmade art tile is well-known. For the past century, Detroit’s Pewabic Pottery is its most historically famous pottery, with recognizable jugs and accent tiles among many family’s heirlooms. Roadtrippers, leaving from here to parts east and south, have likely seen signs for Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati and American Encaustic Tiling of Zanesville, Ohio, or Moravian Pottery of Pennsylvania, or Greuby Fiaence of Boston, Massachusetts. These potteries have become American signatures and archaeologies.

California is home to most notably Batchelder-Wilson Tile Company of Pasadena and Los Angeles, which has long embraced the fusion of American Arts & Crafts sensibility with 18th century Spanish tile. Batchelder’s warm color palette of brown, red, grey, and sand decorate interiors and exteriors of homes and monuments, along with Spanish Colonial style bright azulejos (Portuguese and Spanish painted tin-glazed ceramic tilework) of gold, orange, Mediterranean blue, and white. The look is synonymous with Southern California flair.

Historically, the simple elegance of Arts & Crafts tiles came as a reaction to Victorian fussiness. In 1840’s England, as an alternative to porcelain and cheap “sham,” art tile became a popular decorative accent championing minimalist aesthetic and form follows function thought. Each tile captured a small scene celebrating the simplicity of the region’s flora and fauna. Potteries provided a British regional statement, transforming the handmade works into a pottery of place, many carved with a low relief front design, or made from a transfer print. The glazes, thicker and suited for exteriors and interiors, gave a feel and impression on the senses that many seek as a luxury today.

American artisans of 1870’s influenced by these designs began utilizing the rich clay deposits in Massachusetts, Ohio, and New Jersey. They embraced the ethos of the Arts & Crafts movement, which was a reaction to the social ills caused by industrialization, the degradation of the factory worker, and the cheapening of tools and quality of life. Anne Stewart O’Donnell’s excellent Pomegranate Press book called Motawi Tileworks (2008) explained that the movement was a response to how industrialization had ushered in a spiritual emptiness across society, taking people and families away from the hearth, from the quiet of the reading chair, and from the sacredness of the kitchen.

The mandate of the Arts & Crafts movement was to change the way everyday objects were designed and made to affect change in the world. Tenets included: 1) a celebration of craftspeople putting “head, heart, and hand” into what was made, 2) to operate in a collaboration workshop akin to Medieval guilds, 3) to have design arise from materials used, 4) to elevate everyday objects to the status of fine art, 5) to reinterpret the history of a region or country, and 6) to favor simplicity.

With great success, Motawi Tileworks is embracing these tenets and fusing the artisan guild ideal with modern manufacturing and purpose-driven, small business best practices. It is, according to Motawi, the next gen, the revival.

A Little About Nawal

Nawal Motawi is comfortable being described as an Ann Arborite. She is studied up on her favorite topics yet casual and approachable. She has a visually poetic manner of speaking—always connecting the tactile, the worldly, and craft with ideals and arcs of time.

Unaware at first that her creativity would come from business as much as from art, she was in the same wave of thoughtful small business owners as Zingerman’s and Moosejaw. Her pottery, like all regional responses to an anchor guild, is part of a greater Detroit community of artisans that were inspired and trained by Pewabic, like Dave Ellison and Whistling Frog Pottery.

Vivid, sharp, and an incredibly gifted artist, this past winter she recalled her history with enthusiasm, candor, and good humor from her office, her booted foot propped on a chair (the injury: dancing in Europe). If there is a definitive impression one gets from meeting her it’s that she has a really wonderful laugh.

Now age 54, she is the mother of a son, Kitson Dong, a Michigan State student (he has never worked for her). She loves to spend evenings doing partnered social dancing with a community of close friends and is an avid fan of Celtic and traditional French music. Her reminiscences have an appreciation for folly, like when she told me of the shock of their biggest mural commission—for Disney’s The Grand Californian Hotel—being completed in the wrong dimensions. She is also upfront about not wanting to waste time going after ill-defined calls for public art: “The truth is…there’s artists who make what they make. And you just gotta want what they make…”

Currently she owns a 1950’s Cape Cod in the Haisley School neighborhood. As one might imagine, the three homes she has owned have contained various levels of monument to her craft, with her staff eager to know what she plans to have them install next.

For ten years, she and her ex-husband renovated a home near Skyline High, reinventing the kitchen twice, putting on an addition, and creating the absolute Taj Mahal of bathrooms (“a gorgeous shrine…because I could!”). Perhaps her team’s most ambitious project—the shower’s floor to ceiling dark green and turquoise Tapestry floral tiles are spectacularly breathtaking. One can only imagine chancing upon that at a showing. She ended the report on that experience like this: “So when I divorced that bathroom—[laughing and falling over] and the house…”

Read related article: Visiting Da Vinci

She followed with why she looks for boring blank slates when she’s with a realtor: it has to be a house she can do some tilework in. “Whenever I do a project, when I design a project—which is not that often, it’s going to be a really close friend or it’s my house—what I come up with ends up really influencing the design that comes out of Motawi for a while, which is cool. Because I do something different, naturally…. It takes me a while for a different solution to appear.”

The Early Days

“In high school I hadn’t even met clay,” she said. Then, she looked away and asked, “Have you ever thrown a pot?”

Centering is a thing. And pulling up a cylinder. It’s kind of like riding a bike. Once you can center and pull up a basic cylinder, basically that’s not going away. So, I could do that in high school, but I wasn’t really entranced by clay then.

So, I went to art school at Michigan. And actually, after a year and a half, three semesters, I dropped out in disgust! [Laughter]…. Said screw it, I want to go do something else. I want to lead outdoor trips for a living… I did that for a year and a half and it wasn’t really panning out for me.

And then I went back to art school…and finished my fine arts degree. And that’s when I found ceramics.

After Motawi graduated she joined Pewabic, where a good realization came that she didn’t like working for other people. It was a statement she would repeat, though always with laughter. Her desire to attend a graduate program in England was not possible with her many siblings still in college. Her mother came up with an alternative if she really wanted to be a ceramicist: they would buy her a house and rent it to her and her friends. Her mother wisely counseled, “Why go learning more? Just do it.”

Like many young postgrads whose hearts are in many places, she had a boyfriend at the time who lived in Martha’s Vineyard. “My mom gave me the stare. You’re not going to leave me with this house and go off with your boyfriend in Martha’s Vineyard, are you? No, no!” Within three years the business outgrew the house.

At the time, the only tile store anyone had ever heard of was Color Tile, a chain store selling four and a quarter, the standard size for U.S. tile for years. In the garage she started doing glaze tests, painstakingly mixing her own, sampling clays from different makers, and showing at the Ann Arbor Farmers’ Market.

Using the four and a quarter concept, she first thought she would have to make decorative accents that could be incorporated into those limitations. The goal would be to get a full installation ordered, like the ones she saw made at Pewabic. Only thing was, she was not exactly the savvy in demand interior designer of 1992. In her wonderfully open way, sheepishly smiling and fluffing her hair, she described herself as a twenty-nine-year-old wanting to land an installation:

And I really wanted to be able to do that. I, you know, frankly, I kinda knew I could. But I did not, um, I didn’t present well. You know, I was kinda a punky kid. And you know, my hair messy. I was always dirty. I was always covered in clay. And I was kinda impetuous and immature, I would say. And so, when some of those jobs came open, they didn’t even come open. [Laughter]

Her big break came in 1993, when a local lady who was already “comfortable with artists doing commissioned work at her house” bought a duplex in Ann Arbor, and shook hands with her at the farmers’ market. Still wide-eyed at the reminiscence, Motawi, whose installations will now revise any home renovation’s budget, enthused:

When she came to me, and you know, at the farmers’ market, and I invited her to the garage, which was, you know, a garage—and showed her these samples and asked for 250 bucks for a design deposit. You know, that actual moment I will never forget it, because I asked her for a two hundred dollars non-refundable design deposit to draw up the thing and she said yes!

The heat of the victory still available, she ended the anecdote smiling and throwing her hands up. The neighbor at that duplex bought the next installation.

When The Ann Arbor News did a write up about that first fireplace on North Fourth Street, Motawi was on its way to becoming a name around town. Soon came going to art fairs all over the place, selling gift tiles, and showing people installation concepts. Of her early marketing: “I took pictures with my Tele-Instamatic...I know!”

It took several years to get to a point where “it felt like survival wasn’t the issue, that we were having choices about how to thrive.” It became apparent the business had to evolve to be process oriented. The basics of craft at the Tileworks are very physically demanding: working with heavy clay, putting up a mold, pressing, carving, edging, and kiln firing — all very “wooly” propositions. Then the application of their dazzling color palette: dipping tiles in glaze or the fine hand work of glazing with a bulb syringe, which is akin to making lace, followed by firing and finishing.

She found out early on that she is not interested in being the only manager. Admitting this is not her strength freed her to be a better boss.

The big discovery was visionary, founder, artwork: that’s where my talent is. Any outsider maybe can see that. They might think I’m a good manager, and I would say, no, I’m not a nurturing, kind, coaching person. And I’m too chicken to hold people accountable to their face. You know how Michiganders are, it’s a Michigan thing. That’s a human thing.

It’s not a nice thing to tell people to their face how they are doing, and I don’t have a nice way of doing it. Which really good managers have; that can say, here’s the expectation, here’s your behavior, and we need to get you here. I can describe it, but I can’t do it.

This challenge has motivated her to grow the business. The guild concept would have to modernize into a more intentional workspace and a factory led by industrial processing managers.

The challenge had already been for the bulb glazers to get up to a certain speed without mistakes so that a tile could be sold as a first or sold at all. As they scaled, the challenge would evolve to become how to make fine art tiles in a consistent manufacturing process.

A major part of the solution would be investing in heavy equipment. The acquisition of a RAM press for pushing clay into molds demanded more space than the garage could fit. After her parents sold the house, operations moved to North Staebler for seven years. The facility, tucked behind a towing shop and across from the Kiwanis drop-off, was, to sum it up with Motawi’s own word, icky. The building has since had the ceiling cave in — “the business incubator…ha ha ha…a total dump.”

What was to follow really set the tone for the ascension of the brand. Motawi and her family members pooled resources to become owners of a warehouse sized modern building —“glorious and giant.” She has since bought everyone out, becoming the sole owner of the facility.

The possibility she felt moving in to Enterprise Drive was incongruous with the times. Going big was a risk, especially as a house poor business in autumn of 2001.

It was great and scary at the same time. Because right when we got it and moved in…9/11 happened. And so we were all here making tile when the planes hit, and the phones stopped, and the orders stopped for two solid weeks…. You know, when you are out here in a building that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, you’re not messing around anymore. Yeah, so, I was in deep on it.

Embracing her new responsibility as an investor opening the doors to a pristinely renovated new location, this was her baby. She had to balance the feeling of wanting to protect everything with the reality that she and her band of artisans would be working this place hard. With amazement she recapped that first day and the feeling of okay, be gentle with the property:

So, it was great. The floor was clean. Now it’s all worn out. [Laughter] I remember we epoxy-ed the floor before we came in…it was beautiful. And the first day we came in and showed the staff, and one guy came in and he sorta whipped open the back roll-up door, and it didn’t have stops on the end, so the whole thing rolled over and then fell on the ground! [Laughter] He ripped a whole door off! Nobody was hurt….

These days, when you enter the iris bordered entrance to the Tileworks, what they have created is beautiful. You are immediately immersed in a tiered display of decorative tiles for sale in the gallery. Rows of lush art tile in the hallways compose examples of concept and motif.

Multi-hued sample installations adorn a meeting room intended for customers to go over plans with their designers. Installation planning is a mind-meld more than the designer taking the reins. Colleen Crawley, the senior installation designer, is the employee who has been with Motawi the longest. Her typical clients are either those who can readily make the financial decision or homeowners who have been idealizing an installation for years.

Producing solid Arts & Crafts revival pieces is basically what the Tileworks stands for, and Motawi shrugged in her self-effacing way when she said the brand does not have snob appeal yet: “It’s not like people are coming because they have to get Motawi in the house. No, we get clients who really, really love it [the tile]. And so like, they’re sweet. They are really usually easy to please because they love the tile.

People connect with the natural beauty of the tile. Keeping things close to home, the Tileworks self-distributes; they do not employ remote sales people. Their website emphasizes Motawi chooses designs “that are true to our spirit and present them in our distinctive way.” With her typical candor, Motawi joked that there would be no Kokopelli. “We’re not going to do a Keep Calm and Carry On tile!” Their audience is Arts & Crafts. It’s narrow, and she’s fine with that.

Mining For Better Results

Taking control of the process has been a hallmark of Motawi’s evolution. In 2011, their clay supplier was going out of business. Feeling confident that she knew enough about business, she bought the company to control her supply.

Admittedly, it’s a very different business and the cost drivers are really different. So, it’s been really challenging. It’s working now. But it took me a long time to realize, to bring in seriously expert experienced management and people who knew process inside and out.

In lieu of expecting her usual creative types to know how to manage people and run a clay supply, she turned to the auto industry to find her solution, hiring an automotive industrial process engineer used to managing a plant, as well as another manufacturing manager, to run Motawi and Rovin production. That transition has been one of her biggest wins.

Rovin Ceramics, located nearby but not at the Tileworks, supplies Motawi, but also sells to schools, colleges, and artists. It’s taught Motawi about the elemental realities of her material supply: which clay mines matter, what veins to go for, what trace elements can throw you off, and an awareness of the availability of sourcing.

When asked if the arc of her familiarity with process—reaching back to when she was an art student to knowing the mine level of elemental clay arriving—if it affects some of the more fanciful choices she gets to make during the day, she laughed and said it has less to do with what is learned than what you can improvise. That, for her, being “super creative” is as much about having a compulsion to make designs as it is her coming up with solutions to an issue, no matter how mundane. The beauty of ceramics inherently balances scientific control of the process with form. The business of art, as she wants to practice it, inherently balances creativity with creative leadership.

Read related article: Feminism. Beauty. Queer. Art. Patriotism. Democracy: A Conversation with Local Artists John Gutoskey and Jen Talley

In 2002, ten years in and facing a recession, she looked at the balance sheet and the take home pay and told her team, “This isn’t enough. We need to be doing better.” They started looking up lean manufacturing.

It started a revolution. Their model changed to being a factory for fine art; whereas before, it was a workshop where you could expect a delay on your order. “The reputation was kinda good, the tile was pretty, but delivery was bad, and it was really chaotic, and that’s not very fun,” she said. Scrambling to make enough tiles for each customer, having issues with communications as they assembled orders, all while maintaining standards and efficiency, would push them into discovery as purpose-driven small business owners.

A book had just come on the market called The Toyota Way, written by Jeff Liker, a professor of industrial and operations engineering at the University of Michigan. His research team posited that you could use Toyota production in an opposite manufacturing situation; such that Toyota’s high volume, low variability model (making a lot of cars) could be applied to a lower volume, but high part variability environment like Motawi’s. Liker could not find enough case studies, and Motawi Tileworks agreed to accept his free advice and become one. It made them identify with being a manufacturing process: “It changed us, it changed me in a huge way. Suddenly I feel like a manufacturer. And I know how much we can make today and tomorrow.”

The biggest discovery was the Kanban system, which she said “changed Motawi into something that was fun again. And controllable.” The defining feature of the system is a huge communications board that shows workers how much of each item needs to be manufactured. Eliminating managerial conversations, it plainly communicates priorities. There is beauty in its simplicity, keeping worker and manager happy: “The system tells people what to do…. The creating of the system is fascinating and the tweaking of the system is fascinating. Because who wants to order people around all day long?” she said imitating a snore. The same is true that no one likes to be ordered around. It’s better if everybody understands what the goal is and what’s needed to meet it. Kanban liberated their practices.

Undertaking a major business decision about operations with a small, close-knit staff was hard. Their consultant, Eduardo Lander, coached them through the growing pains. They had to embrace a forward progress and accept the notion that a new model was not putting people out of their jobs but being more effective with what they had. As she put it, “We’re not getting rid of jobs. We are creating more value with the work that we’re doing.” Scaling operations is never easy for a small outfit, yet she was relieved they switched. Her recollections of that time are the tender statements of an empathetic small business owner.

Feeling empowered by putting in place better management, and being intelligent, curious, and eager to study business principles, Motawi jumped into applying better practices throughout. The vision statement adopted the 14 principles of Toyota, among them the famous distinction to “create a continuous process flow to bring problems to the surface.” They delineated an employee-focused approach, influenced by the ethos found in Small Giants: Companies That Are Choosing To Be Great Instead of Big.

They were galvanized to take care of their employees across the totality of their lives. Health insurance, life insurance, a retirement program, and a workplace that is healthy physically and mentally became documented standards. Employees are encouraged in a caring, individualized way. Gleaning wisdom from Gallup research, they brought into practice that employees do better with clear expectations. Each process became documented and official. The workplace is also intentionally social, joyful, and kind. It sounds simple, but it’s a big job to control as a boss. Motawi does it with aplomb.

Being transparent and sharing a lot of information with the team “so that everyone can put their brains on it if they want to” is their embrace of the Toyota ideal. Acting with integrity and right by their vendors and suppliers, and the people they work with, is the culture. “The last thing I want to care about is shareholder value. So, it’s a human scale company. People know each other, people care about each other,” she said.

Though Motawi says she is not cut out to be mostly a manager, recalling that over the decades there have been people who have stormed out, her standards suggest that her years of managing have made her a sensitive boss. “I don’t assume that what works for me works for other people. With this whole Golden Rule thing. The Platinum Rule is do unto others as they want to be done unto. It doesn’t have anything to do with you and what you want…”

She is also an example of dedication and hard work. Her longest vacation was three weeks, as was her maternity leave. Hopefully, as she hones a succession plan “emergency or otherwise,” freedom will be a benefit she reaps. Her near-term goal is a sabbatical.

Outreach and telling their story with joy is part of why many locals have been to Enterprise Drive. Members of the public can tour the Tileworks to see and feel the installations, as well as learn about Motawi’s take on a modern guild system, with its RAM press, CNC machine, glaze area, and kilns. If you go during production hours expect to be hot with the kilns firing.

Twice a year they host a very well attended open house and sale of tile seconds, lined up in rows for art collectors or prospective remodelers to browse. Kids can see that “there’s people making things! It’s not an app!” Potters and amateurs alike can join Make-A-Tile. Taking place under a tent outside, for five dollars they will give you clay and tools to design your own square. Later, all tiles are fired with the same glaze, available for pick-up in a few weeks as a present you planned for yourself. On the feeling of Make-A-Tile, she mused:

It does make my heart swell to walk around and see all different ages of people engaged. They are talking with each other. Some of them are wracking their brains because they don’t want to make a bad tile, you know. It’s focused and positive, the energy. And I know people come year after year…That’s just worth doing.

Sweating out their design under the tent, the public gets a small window into what it takes to do a fine art tile. The notion arises of how can a bulb glazer do this all day? If the yin is the bulb glazer at work, what is the open work, the release of focus, the yang for that person? Not surprisingly, Motawi said the answer is that joking around and humor are encouraged. “Go kibbutz for a few minutes, it’s okay.” Motawi is also hiring with harmony in mind. There is considerable turnover, as there are with many factory jobs, and upbeat, hard workers thrive here. The happiness of the staff is apparent when you visit. These are artisans and craftspeople taking pride in their work.

Motawi Tileworks is located at 170 Enterprise Drive, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48103. The Tileworks has 60 to 90-minute tours Tuesdays and Thursdays, and docent-led 20-minute tours on Saturdays. Locally, look for their gallery at the Ann Arbor Art Center. Visit their website for details and a portfolio of installations at motawi.com.

Related Articles:

I don’t know about you, but I am constantly misplacing my sunglasses in my bag. I eventually find them, and inevitably the lenses are scratched. I’m determined not to let this happen this summer, so I made a cute little glasses case to help protect them. I made this case on my machine, but you could hand sew it as well.